Parish histories are common enough and each serves its purpose. Few however are as comprehensive and well-researched as the one recently published by Carmyllie Heritage Society,

The book’s editor Anne Law and her team of contributors have, in 180 pages of text and illustrations, produced a nugget which deserves to be cherished by future generations. Carmyllie is only one of 62 parishes in Angus, but in many ways is typical of the county. Geographically it sits at its heart and, like so many others in lowland Angus, it is distinctly rural in nature.

Dubbed ‘Cauld Carmyllie’, it sits higher than many of its neighbours and its inhabitants have, especially in times past, had to work hard to wrest a living from the land.

As with so many Angus parishes it has no central village. Instead, it is made up of a scattering of smaller communities. As the book, Carmyllie Its Land and People, explains, there are very good reasons why this should be so.

Many of the inhabitants made most of their living in earlier centuries from hand-loom weaving on the ‘putting out’ system. Pack horses would deliver linen yarn from Dundee on a weekly basis to these clusters of cottages and take back with them the woven web.

In the years before full factory mechanisation, this made sense for all concerned. The textile merchants had no need to house their workers, and if times were hard and demand was low they simply suspended yarn deliveries.

There would be hardship no doubt for the weavers, but at least they had their pendicles or crofts to live off. They would neither starve nor go homeless even though they would have few luxuries.

These pendicles, often just big enough to support a cow and grow some oats and kale, were therefore of necessity scattered across a parish measuring roughly four miles by three.

Mrs Law and her team have wisely concentrated their history on the 130 years from 1840 to 1970. Source material for earlier years is harder to come by but, apart from that, this chosen period is surely the richest in the life of the parish.

Carmyllie has always been a farming parish but, in common with many of its neighbours in lowland Angus, it had quarries.

In Carmyllie’s case these produced the highest quality grey sandstone pavement, and in late Victorian times the demand seemed insatiable.

The quarries at Slade near the hamlet of Redford were soon turning out pavement slabs, doorsteps and window lintels in industrial quantities and with the boom came new employment opportunities.

By 1871 the population of Carmyllie parish had peaked at around 1,300.

Now it is something around half of that, but memories of the quarries live on and have been faithfully recorded in the book.

Lord Panmure, who owned the quarries, quickly realised that lack of transport to the harbour at Arbroath was the limiting factor.

By 1885 he had funded and completed a railway which ran from the main line at Elliot right up to the quarries at Redford. In just five miles the line climbed from sea level to 600ft.

The combination of the new railway and steam-powered stone-cutting machinery soon meant that several train loads of stone could be despatched every week. The wagons went up the line laden with coal, fertiliser and lime and came back with stone.

Passenger services were introduced from 1898 until 1929 but speed, or lack of it, was always an issue. Jokingly known as the Carmyllie Express it nearly always ran late. Sometimes, apparently, the driver would stop along the way to set rabbit snares and then check them on the return run.

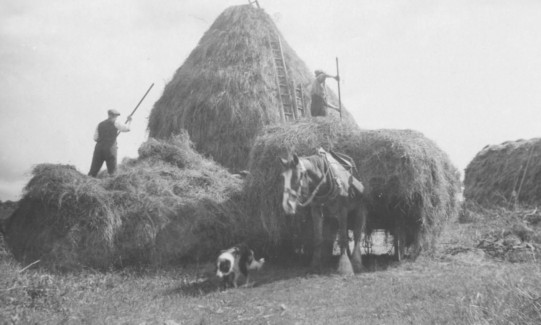

The agricultural history is well covered, too.

During the period in question there were three main landowners, Lord Panmure with his holdings in the west and centre of the parish being the greatest.

The Ouchterlonys of the Guynd had a substantial holding around their grand house and gardens, and to the east was Cononsyth Estate with its mansion.

Commissary Maule in the Registrum de Panmure of 1611 described Carmyllie as “ane pair place fit only for bestial (cattle) in summer”, but, as the years wore on, human endeavour turned it into a more fertile area.

The soil, which Maule noted as being only seven inches deep in many areas, was constantly improved by successive generations of tenants.

They spread lime and added guano as fertilisers. They dug drains and built dykes to enclose their fields, all the time complaining that the lairds kept using these improvements as a reason for increasing the rent.

Gradually the pendicles became absorbed into larger farms, but the farming remained predominantly based on cattle and the crops needed to feed them.

Carmyllie had its own monthly market at Redford, with the buildings and pens only removed as recently as 1971.

Local cattle were driven to the market on foot, with the Carmyllie Express hauling in wagon loads of Irish stores until the line closed in 1956.

The book describes in great detail the influence the three main landowners had on all aspects of life in the 19th Century.

Along with their contemporaries across Scotland, they had the right to appoint the parish minister. They favoured Episcopalian preachers, whereas their tenants and villagers preferred a more Presbyterian approach. This culminated in the Disruption of 1843 and the formation of the Free Church as a “church of the people”.

Carmyllie was rent in two, with around half the Church of Scotland congregations seceding to the Free Church.

They weren’t quite persecuted by the Lord Panmure of the time, but he made sure for a number of years that they had no permanent place of worship.

The tale is told of the tenant farmer at the Firth being offered a rent reduction if he returned to the Established church and persuaded his fellow tenants to do likewise.

He seemed to have been largely unsuccessful and, ironically, died in the middle of the first harvest thanksgiving service after his infamous deal.

Over time the Free Church was able to build a church and manse at Greystone.

Schools were built in both the east and the west of the parish, and universal education slowly gained traction. Attendances were, however, very much affected by the seasons, with the classrooms emptying when the children were needed at home for harvest or potato planting.

There is far more in the book than can be reviewed here. It is a rich tale of rural life in lowland Scotland, and it is a story well told. It is a good read but, beyond that, it is a reference work that deserves its place on the shelves.

Carmyllie Its Land and People is available from: Corn Kist Coffee Shop, Carmyllie; Letham Post Office; Arbroath Library; McDougall’s Newsagent, Carnoustie.Or email: jalaw1@btconnect.com; douglas.norrie@virgin.net. See also website: www.carmyllieheritage.co.uk.