The north-east of Scotland was a key target for penetration by Stasi leaders during the Cold War.

The Stasi’s motto was “Shield and Sword of the Party” and the secret police attempted to coax Scotland’s academics into spying for them.

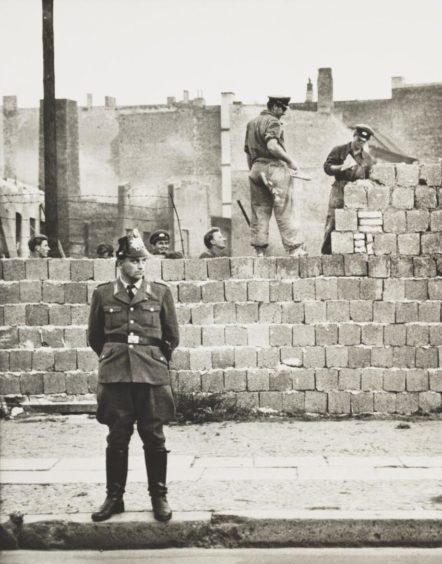

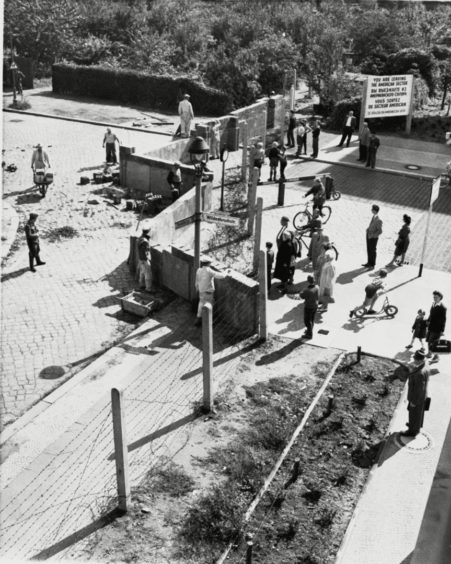

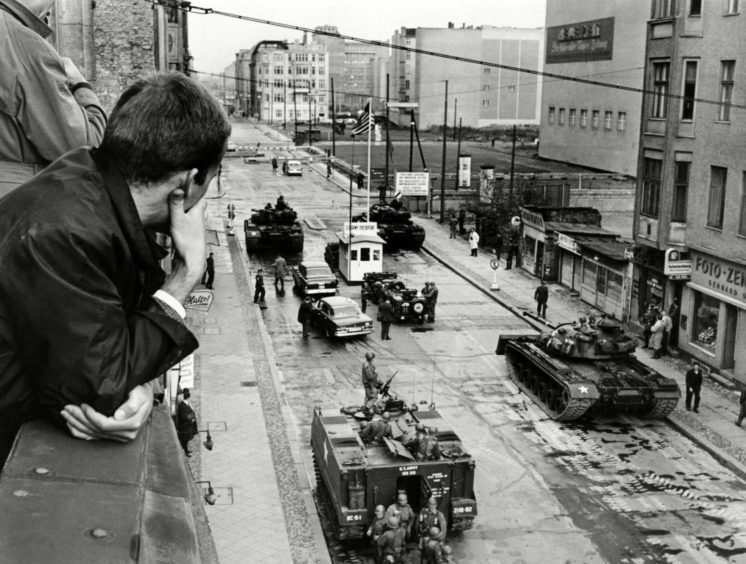

By the end of 1989, the Stasi consisted of more than 90,000 official personnel and up to 170,000 agents, before the secret police collapsed with the Berlin Wall.

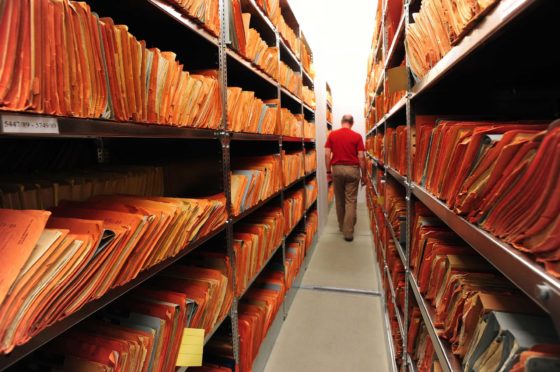

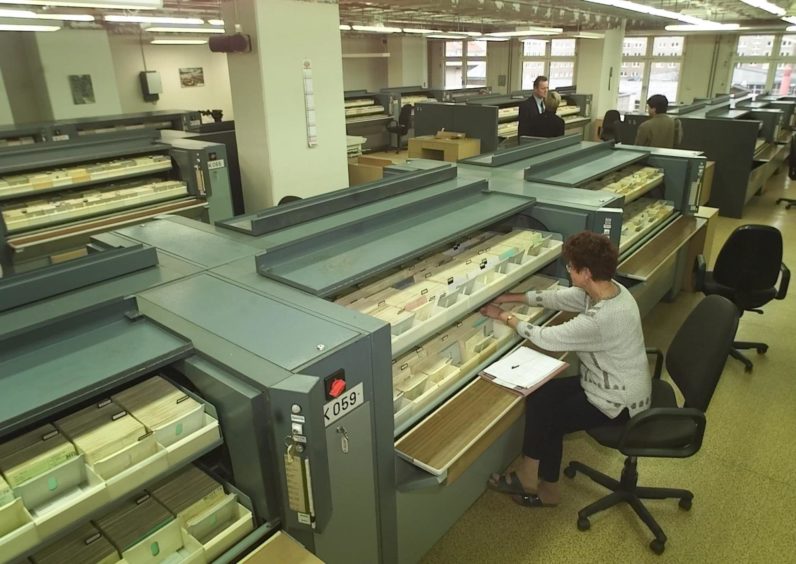

Protestors broke down the doors of the Stasi HQ 30 years ago in 1990 to prevent the destruction of more than 100 kilometres of intelligence files, 1.7 million photographs and 34,000 film and audio recordings.

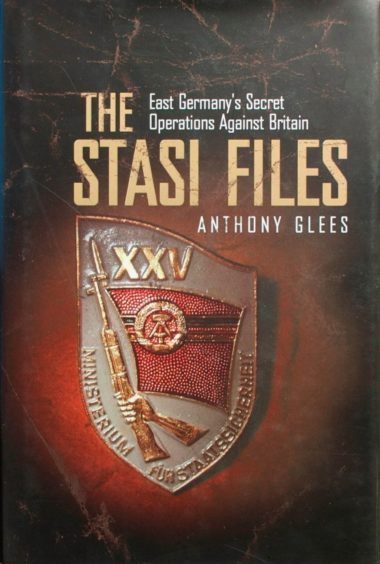

Intelligence expert Anthony Glees said Scotland seemed a place “well worth the investment of Stasi interest”.

His book The Stasi Files was the first such study to have virtually open access to the documents and, because of a German court ruling in March 2002, will probably be the last.

He said: “It seems to me that to reflect on the interest shown in Scotland and in Scottish universities by the East German Stasi there are two aspects to this, a fairly specific one and a more general one.

“The more general one is that to the political brains in the Stasi, Scotland presented as a country with a potential desire for greater independence from England, whose many grievances might be turned against England, to allow it to become an ally of East Germany.

“At Faslane, Scotland was home to the UK’s nuclear Trident fleet, a key site for the anti-nuclear CND movement which the Stasi were so keen to promote.

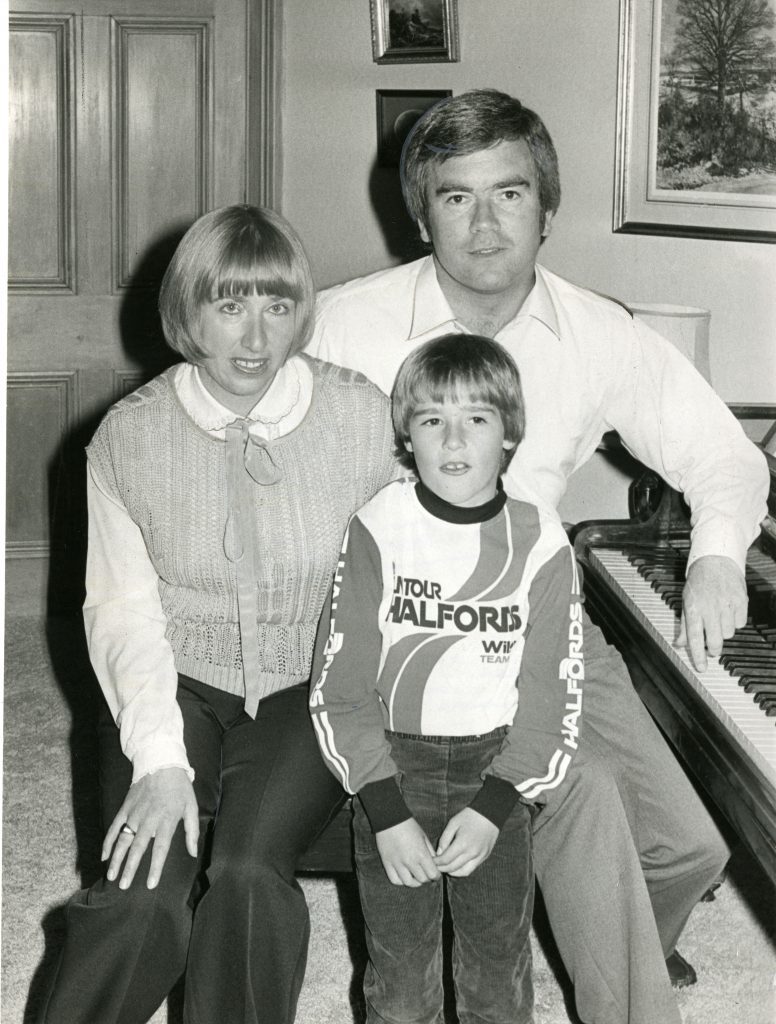

“In 2003 we learned that Helen Anderson from Arbroath admitted to have been a Stasi spy for 12 years, motivated by her support for CND goals.”

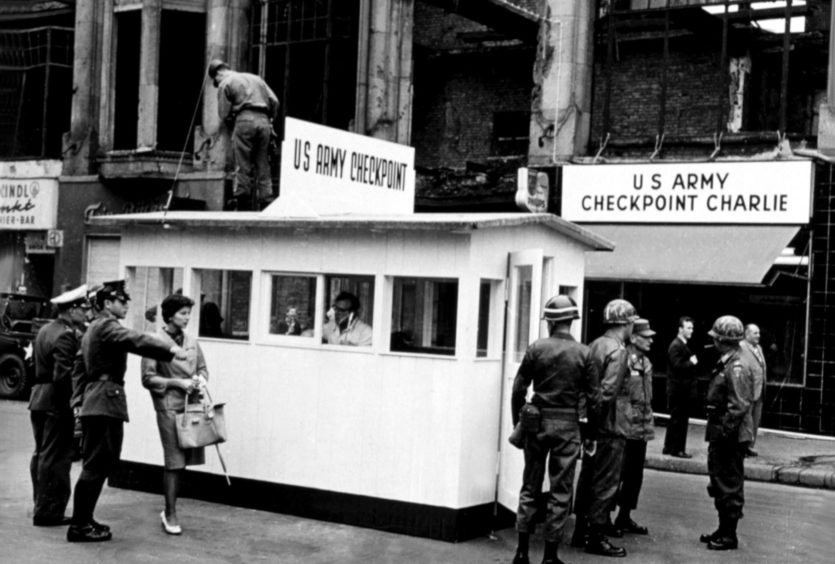

Mr Glees said Forfar-born Helen Anderson had travelled to Berlin as a 27-year-old in 1980 and began working as a secretary for the lieutenant colonel in charge of administration on a US naval base in West Berlin.

He said she was seduced by an agent claiming to be a peace campaigner called Olaf, although his real name was Dietmar Schumacher and he was married with a child.

She smuggled documents out of the base in a handbag with a false bottom and stored them in a special bottle of hairspray before passing them on to East Germany’s security services.

The material included details of American soldiers whose cheques had bounced because the Stasi often blackmailed servicemen in debt.

She was found out and confronted in 1992 but escaped jail after convincing the authorities that she had been unaware of the Stasi link.

She was brought to court in March 1993 but received just two weeks’ community service while Schumacher was given a suspended sentence of one year.

Mr Glees said: “Scotland had a doughty history of strong working class political activism and relatively strong support for Communism.

“Willie Gallacher, the UK’s last Communist MP, had sat for West Fife from 1935-50 and as late as 1973 the Communists won 12 seats on Lochgelly and Cowdenbeath Council.

“It is possible that some East German political strategists regarded Scotland as Scots were often highly educated, probably better educated than the English or Welsh and took learning seriously and, in short, might be won over to Communism by exposure to the East German model which was falsely viewed as more Scandinavian than Russian.

“It won’t have escaped Stasi chiefs that from 1983 onwards, Burns’ Night was celebrated by Scots in East Berlin, together with East Germans, with 60-70 Scottish visitors turning up each year.

“In 1988, we are told, 32 new members joined the Scotland-GDR Society which had been founded two years earlier.

“Organised visits from East Germany to Scotland took place in the 1980s with two visits by the Free German Youth movement.

“In short, Scotland seemed a place well worth the investment of Stasi interest.”

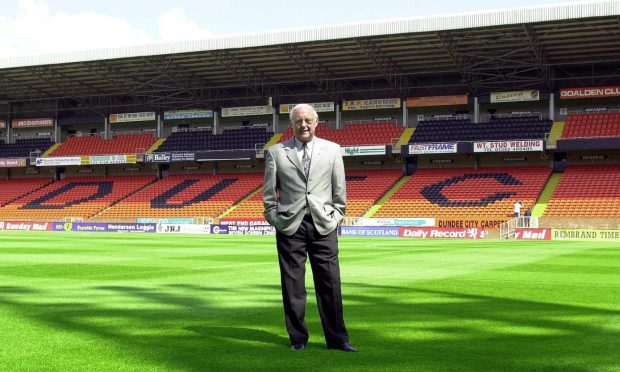

Erich Honecker’s feared regime gathered information on Professor Ian Wallace from Dundee University who undertook research into the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and was a regular visitor from 1977.

His name was included in a list of academics handed to the secret police in 1978 by Edinburgh student Robin Pearson, who was eventually exposed as a spy in 1999.

Pearson’s task was to collect information to provide insights into the motives, the course and the purpose of the UK’s policy of contacts with the GDR.

During his time with Dundee University, as a German lecturer, Professor Wallace organised two international conferences on the GDR in 1981 and 1983, invited a number of GDR, or former GDR, writers to the university as speakers, and also set up Dundee University’s academic journal on East Germany, GDR Monitor.

The Stasi attempted to influence the editorial content of the university’s academic journal on a visit to East Germany in the early 1980s.

The secretary of the writers’ union attempted to get Professor Wallace to publish in the GDR Monitor, some works by GDR-friendly writers, but he refused and it never happened.

Professor Wallace later wrote to the former Stasi HQ in Leipzig after the fall of the Berlin Wall to see if they had any files on him.

He was told at that time that there were not but he stumbled across a couple of files of intelligence while working in a Berlin archive.

Professor Wallace was educated at Oxford, Tubingen and Lausanne, did postgraduate research at Oxford and Heidelberg, and taught at the universities of Maine, Dundee, Loughborough and Bath.

“More specifically, Scotland was home to Dr Karin McPherson, an absolutely key figure in actively encouraging her German language students at Edinburgh University to choose to study in East Germany, rather than West Germany, in particular to go to Leipzig University (East Germany’s premier foreign language study location),” said Mr Glees.

“Just as the MI5 and MI6 toured the UK’s premier universities hoping informally to recruit officers to spy for Britain, so the Stasi exploited foreign and Scottish students at Leipzig.

“One of the most prominent was Graham (now Lord) Watson, a student from Heriot-Watt, at that time deputy leader of the Scottish Young Liberals.

“Whilst the Stasi had spotted a bright star (Watson went on to become an MEP and advisor to David (Lord) Steel), they had failed to spot a loyal Scot and Brit: he told them go away in no uncertain terms.

“If she did not know that she was sending her student into harm’s way we can only assume she was less well-informed about East German politics than she claimed to be.

“Internal Stasi documents reveal that she was described in their books as a ‘progressive scholar, closely linked to us’.

“She was well known as a supporter of the culture of the East German ‘model of real, existing socialism’ (a more palatable alias for Soviet Communism) and worked hard to get East German language instructors to visit Scotland, rather than West Germans (or Swiss or Austrians).

“The UK’s most notorious English Stasi spy, Robin (now Prof) Pearson of Hull University was sent by Dr McPherson to Leipzig. Dr McPherson had retired by 2015 but left to the university her copious personal collection of East German writings.

“Given the interest that the East Germans had in Scotland and that some Scots had in East Germany, the work of Professor Ian Wallace in attempting to provide an academic analysis of East German affairs was a much-needed counterweight.

“However perhaps the most notable thing about this distinguished academic was that whilst for obvious reasons the Stasi repeatedly tried to recruit him, he repeatedly made it clear that he was determined to be left alone.

“Like Graham Watson, his loyalty to democratic values was robust and the Stasi were unable to make any inroads into it.

“This of course highlights the failings of those Scots who were seduced by the East German secret intelligence service.

“In their defence it is not hard to see how the Stasi was able to groom them, using what will have seemed to them the huge resources at its disposal – basically they could make anything happen for their friends – and how some, like Robin Pearson, could be recruited as spies, especially if Marxist and Communist ideas appealed to them.”

The Stasi turned East Germany into a “total surveillance state”

No Communist population was as monitored as East Germany’s.

There was a Stasi officer for every 180 people; by some calculations one in three East Germans were acting at some stage or another as an informant for the security service.

The Stasi kept an archive of sweat and body odour samples, which its officers collected during interrogations.

The Stasi managed to turn the GDR into a “total surveillance state” with mail monitored and phones bugged — all helped by a cowed army of informants.

Mr Glees said: “With hindsight it is depressing to note that today many strategies employed by the Stasi seem to have been copied in particular by China.

“China, whose intelligence agencies mirror those of East Germany, also targets universities and foreign students, understanding that they are a good way of finding friends and recruiting potential spies.

“There is no reason to believe that Scotland is at particular risk.

“However, it will not have escaped today’s Chinese intelligence community that the outgoing head of MI6 came to St Andrews to speak in December 2018 and pointed out that he joined a Scottish regiment from where he was recruited into MI6.

“If MI6 rightly appreciate the rigours and strengths of a Scottish higher education, just as the East Germans did, should we wonder if the same thoughts do not occur to other adversarial or hostile states? Let’s hope Scotland ponders this point.”

The citizens who spied on each other

The Stasi was the most effective and repressive secret police agency ever to have existed.

For four decades from its founding on February 8 1950, it spied on the East German population through a vast system of citizens turned informants who spied on each other.

It’s now estimated the Stasi had one policeman for every 166 East Germans, and an agent or informer for every six.

In comparison, the Gestapo had one officer for every 2,000.

In fact, so effective was the Stasi that it was asked to help set up secret police forces in countries across the world.

By the 1970s, the Stasi had come to the conclusion that overt methods of persecution, such as arrest and torture, were too crude and obvious and decided psychological harassment was less likely to be recognised and thus provoke victims and supporters into active resistance.

Known as Zersetzung – a term borrowed from chemistry literally meaning “decomposition” – the new tactic was designed to sidetrack and switch off enemies so that they lost the will to perpetrate any “inappropriate” activities.

The Stasi would deliberately disrupt the victim’s private and family life by psychological means, breaking into homes and manipulating their contents.

Zersetzung could be plausibly denied by the state and with victims having no idea that the Stasi was responsible, mental breakdowns and suicides were common.

The Stasi’s attention to detail was ferocious. Among its departments was the Division For Garbage Analysis, which was responsible for analysing household rubbish for any suspect and prohibited Western foods and materials.

During interrogations, seats would be covered in cotton cloths to collect perspiration which were then placed in glass jars, so trained dogs could track victims down – underwear was stolen for the same use.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Stasi attempted to destroy its files in January 1990 but even though a billion sheets of paper were shredded or burnt, that was still only 5% of the total.

Today, the old Stasi HQ in what was East Berlin is a museum that demonstrates how they used to monitor and control the population.