Scottish folk love telling stories.

And as any yarn-spinner worth their string will know, the trick to a good story is knowing how to tell it.

It’s a skill that the founders of heritage charity Folklore Scotland, Dundee couple Rebecca and David White, have got down to a T.

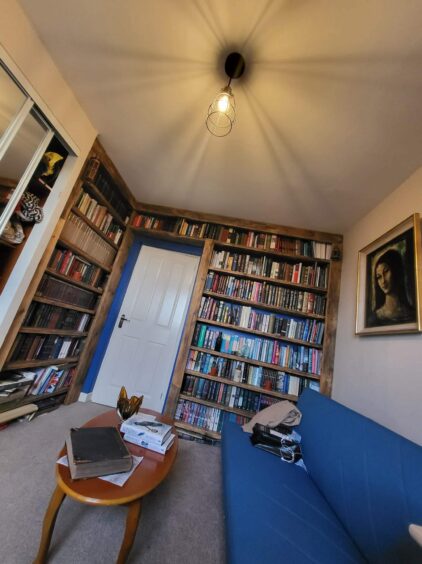

Ensconced in their fairylight-strung, book-laden city flat, the 25-year-old newlyweds are a natural storytelling team.

They ping-pong prompts to one another with the ease of two people who already know the end of every tale the other with tell.

“Shall I tell her the rock story?” Rebecca asks with a twinkle when I ask about the inception of their four-year-strong organisation, started when the pair were both just 21.

“Aye, go on,” comes the reply, and the story which follows isn’t so much about the beginning of the charity, but the beginning of the couple’s relationship – and it soon becomes clear that the two are inextricably linked.

Folklore Scotland – a love story for the ages

“It was the first proper bonding conversation me and David had, before we were going out,” she begins.

“We were at a student party and we’d spent the whole night drinking and dancing. We ended up sat on a bed -very innocently! – chatting about our favourite rocks.”

“Our favourite standing stones,” David clarifies. “It’s how we found out we both loved Scottish mythology.”

“And I remember texting my friend as I left,” Rebecca laughs, “and being like: ‘This boy loves rocks and so do I!’”

The rest, as they say, was history.

And as the pair grew from friends to partners, to husband and wife, their shared love of Scotland’s own history and folklore grew too.

So when they came across the Elevator business start-up competition in 2019, they decided to enter it together with an idea for a storytelling platform.

(Spoiler alert – they won.)

And so it was that they co-founded heritage organisation Folklore Scotland in 2019, and registered it as a charity in 2020.

“After going through the business training, we thought it should be something accessible to everyone, not charged for,” explains trainee solicitor David. “Something educational which would engage people.”

“So we decided it would be a not-for-profit instead!” smiles Rebecca.

Since then, the pair have built up the charity outside of their day jobs – putting in shifts over and above full-time work.

Together with the help of a dedicated team of volunteers, they’ve hosted an art exhibition at Roseangle Gallery, created a website filled with myths and magical creatures from Scotland’s regions, produced a lighthearted podcast examining different legends in pop culture each week (this week it’s Disney’s Brave, and Willo’ The Wisps), and even launched weekly newsletter covering more academic aspects of folklore study.

Not to mention the Folklore Scotland social media channels, which are populated weekly with everything from kelpies and witches to brownies and (Rebecca’s favourite) the “wee bannock”.

“A lot of folklore is very difficult to digest because either it’s written in old Scots, or it’s in these big anthologies, it’s written in a way that people can’t understand,” explains Rebecca, who works as a digital communications co-ordinator at the High School of Dundee.

“So we’ve tried to make it accessible, and digital, so people can more easily find it. And we’ve used different formats to make that possible.”

Folklore Scotland’s ongoing mission, they explain, is to uncover the stories that haven’t been written down or recorded, but are still being told in grandparents’ living rooms and lamplit pubs across the nation, and give them a home.

“I’d really like to try and capture some of the folklore in places that you otherwise wouldn’t get,” says Rebecca.

“Stories people have grown up with about ‘that bridge down the road’ or ‘that tree over there’, but you don’t get that online, because it’s not been preserved.”

Folkore is ‘like a game of Telephone’

And as a keen pro-Independence campaigner, preserving the stories of the past isn’t just a passion or pastime for her – it’s a vital part of mapping out Scotland’s political future.

“A lot of Scottish culture has been reduced to the postcard the Victorians created,” she observes, explaining that much of the folklore we currently have recorded was first written down by Victorian writers who travelled between Scottish villages and picked out the ‘best’ stories to write down and sell.

“And the Victorians did do a lot for folklore [by writing it down],” she goes on, “but it’s just really important for me to preserve these stories and not let them get lost.

“Because we have lost a lot of our stories, and the hold that our language and our culture used to have.”

It seems part of what makes Scottish folklore so fascinating – and tricky – is that so much is unrecorded and improvised, having been originally passed down through generations by word of mouth, “like a game of Telephone”, as Rebecca puts it.

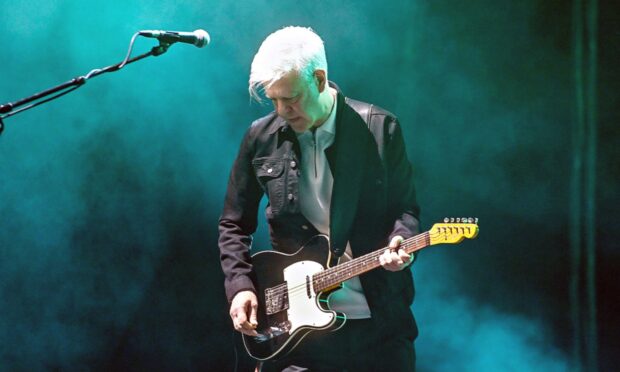

Indeed, when David performed a live oral storytelling session at last year’s Cashel Bash on Loch Lomond, he found it was virtually impossible to tell a story the same way twice.

“I’d learned the main bits of the story, but each time I told it, it was slightly different,” he reveals. “Because you’re telling what feels natural in the moment, what you feel the group will adapt well to.”

“And answering the questions of children!” Rebecca interjects.

“Yeah, children have a lot of questions about the technicalities of faerie creatures.

“They had a problem with the sea witch, because they said if she’s a witch, she should melt with water. They weren’t very happy with that concept,” David adds wryly.

‘It’s about coming round the hearth’

He’s joking, but it speaks to a wider issue – the resistance to a changing story or multiple truths in the era of ‘fake news’ and intellectual property.

“I feel like we don’t have as much of an appreciation for a changing story nowadays, because of the impacts of print media,” Rebecca notes, picking up that thread.

“We like a story to be the same; this is the story, this is how it’s told. Whereas there’s a kind of beauty in picking the bits out that you like.”

“That’s what I really like about folklore,” her husband chimes in. “In one way it’s very individual because it’s how you’re constructing this world in your head – it’s your fairies and kelpies and selkies running about.

“But also, it’s a lot to do with community, because everyone who has worked with that story or read it before has done something to it.

“It’s all about coming round the hearth together and sharing stories, and developing folklore in a way.”

It’s true; to pass on folklore is to play a part in its communal (re)creation. So why is so much of what we now consider ‘folklore’ old, historic tales?

David points out that as spoken Gaelic dwindled, young people moved to cities and communication between generations broke down, so too did the practice of oral storytelling and creating new tales.

But does that mean no new folklore can be created in a modern, digital Scotland?

‘Nowadays it’s conspiracies and cryptids’

“It’s interesting, because back in the day we’d tell stories about kelpies and water monsters because lochs were really dangerous, you know?” muses Rebecca.

“You shouldn’t go near the loch because you might fall in and drown, things like that.

“Nowadays, it’s hard to see folklore from when you’re in it, but the one thing that springs to mind is conspiracy theories and cryptids like Bigfoot, that kind of stuff.

“Things like 5G towers! People tell stories about them because of the paranoia around them.”

Notably, much of what Rebecca references as modern folklore isn’t particular to Scotland.

And while folklore can be defined by geography, Folklore Scotland also embraces the idea of a cultural mythology which extends beyond regional – and even national – lines.

“I think folklore has always been quite international,” observes David. “A lot of places share similar stories or similar characters. Dragons are a classic example – they were everywhere!

“So I think a lot of it’s a story of a time than a place.”

It’s an idea which is particularly intriguing in the age of the internet, when cultural phenomena rise and fall in rapid real time, and the word ‘era’ can mean anything from a week to a decade, to a Taylor Swift album cycle.

Is TikTok the new folklore?

“In a weird way, a modern equivalent (of oral storytelling) might be TikTok, and TikTok trends,” posits Rebecca.

“Because they will start out with something that someone has posted. And then people will take that and replicate it, change it, make it their own – and then suddenly there’s almost this mythology from the original post to all these interpretations.”

One current example of this is the mascara trend on TikTok, where creators review different ‘mascaras’ as a code for talking about their romantic histories.

@emmthevirgo

“Everyone knows what it is,” Rebecca goes on, “even though it’s spiralled and changed totally from the original!

“So it’s not quite folklore in the way that we know it, but I guess you could say that it is some kind of folklore.”

One thing is certain – whether it’s hushed pub whispers in a far-flung village with a funny name, or a 30-second clip made in a 2023 teen’s bedroom, David and Rebecca agree that there’s something so special, and quintessentially Scottish, about the nostalgic nature of folklore.

The question is, what is it? What is that quality which keeps Scots suspending their 21st Century disbelief to delight in faeries and phantoms?

“I think Scottish stories are just fun!” muses David. “We’re whimsical, we’ve got quite an eccentric nature and that Scottish sense of humour…”

Rebecca’s hand flies up, epiphany-like: “Also, we have whisky!”

Now that might explain a wisp or two.

Conversation