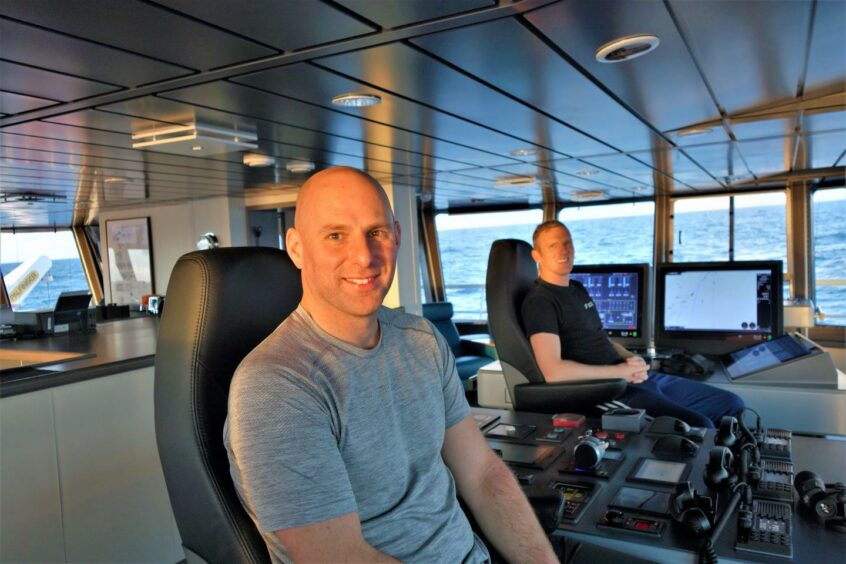

It was just prior to daybreak and the tension in the wheelhouse of the Fraserburgh-based Resolute was palpable.

The trawler was 18 miles south-east of Sumburgh Head, Shetland, and for the last few hours, co-skippers Matty West and Ally West had been tracking shoals of mackerel with their electronic fish finding equipment.

Illuminated by the gentle glow from the large fish-scanning and navigational screens arranged at the front of wheelhouse, the faces of Matty and Ally were a picture of rapt concentration.

‘There’s a good shoal there…’

Pointing his finger at one of the fish finder visuals, Matty says: ‘There is a good shoal there, but let’s steam on a bit more and see what else we can find.”

He explains the digital patterns on the screen which signify fish.

To a layperson, they appear like vast orange smudges, but to Matty’s experienced eye, he can quickly tell the size of the shoal and the direction they are heading.

What is immediately apparent from the digital shoal signatures is that there is an abundance of mackerel in the seas off Shetland – an encouraging sign the stock is in good health.

The shoal that Matty was tracking was around three miles long and 150ft deep.

The screens also highlighted the position of two other fishing vessels a few miles away, who are involved in a similar search.

Matty and Ally, who are cousins, alternate between who is lead skipper for each trip, and this time around Matty, 41, is in charge.

“When possible, we prefer to shoot the trawl when it is daylight, as the mackerel tend to shoal closer together during the day, and it is also safer for the crew,” he says.

“Tracking the fish is always an interesting time and we are continually weighing up our options.”

According to Ally, the two-skipper arrangement works well.

“It’s really useful to have someone else to confer with when discussing the tactics for the day, and to sound out the various options open to us,” he says.

As the flickering light of dawn gradually took hold over a grey-ruffled sea, the 10 other crew members scrambled down to the lower stern deck to prepare the trawl for shooting.

It is a complicated task, shackles were attached here and there, ropes prepared, and the tail-end of the net was hauled up from the winch by a specially designed crane, before being hung over the stern.

It was a study in teamwork, the crew going about their tasks quickly, efficiently, and methodically, each one knowing what their colleagues were doing, and working together as if guided by telepathy.

It was truly impressive to watch.

Matty steers the 69m vessel carefully towards the shoal which is swimming in midwater at a depth of around 100m.

He cuts the speed to 1.5 knots and gives the order to shoot the trawl, the air suddenly fills with a clamouring, metallic clanking noise as the winch rapidly unwinds, the trawl trailing away behind the vessel into a gently heaving sea.

The Resolute slowly tows for about 45 minutes – time for the crew to snatch a quick breakfast – before they are back out on deck again as the winch begins to slowly retrieve the net.

Once the net bag at the end of the trawl was safely secured by the stern of the vessel, the mackerel were pumped onboard into refrigerated seawater tanks, which keep the catch at just below freezing point.

During this entire period, hordes of gannets and gulls swirled excitedly around the Resolute, and we were even joined by a pod of orcas, feasting upon any mackerel that had spilled into the sea.

This turned out to be a good haul of mackerel, each fish averaging about 435gms, and once the net had been emptied, the trawl was released back into the sea for one more tow after another mark of fish was detected.

Slightly fewer fish were caught this time, and they were marginally smaller compared to the first haul, but Matty and Ally were still well pleased with the morning’s work.

Everything went like clockwork

Everything had gone like clockwork, and this had been a good morning’s work.

The Resolute swung around and headed back towards Lerwick to land its catch at the local mackerel processing factory, some four hours steaming time away.

The quality of the catch is important, and Matty and Ally were hopeful this consignment would attract the attention of discerning Japanese buyers.

Much of the previous landing the day before had achieved just that, resulting in a higher price for the catch.

After landing, the fish are frozen whole and packed in cardboard cartons, ready for shipping to export markets such as Japan, eastern Europe or West Africa, or for further processing in north-east Scotland, including smoking and canning for UK supermarkets.

Mackerel has undergone a remarkable transformation from a fish of little interest to the Scottish fishing fleet prior to the 1970s to the current position of being Scotland’s highest value and volume catch.

It was worth £218m at first point of sale in 2020.

Mackerel is increasingly in demand

In the 1980s and early 1990s much of the Scottish mackerel catch was sold direct to Russian and other Eastern European country factory ships – or klondykers as they were popularly known – anchored off places such as Ullapool and Lerwick.

But in more recent times mackerel has become an increasingly sought-after fish in the global marketplace and the klondykers have long gone.

They were replaced by modern state-of-the-art onshore processing plants in the north-east of Scotland and Shetland, which employ in total around 2,000 people.

Generations of fishing families

As is the case with other mackerel and herring vessels in the Scottish fleet, the composition of the crew of the Resolute is largely a family affair, with many related to one another, and coming from fishing families that can be traced back several generations.

Ally West , 37, says: “Fishing really is in our blood and there is no job in the world quite like it. The satisfaction of completing a successful trip gives you an unbelievable buzz that is difficult to describe.”

Matty agrees. “Every trip is different and brings its own different challenges, but I enjoy the job immensely, especially the camaraderie involved when working with such a great crew.”

After this landing, the Resolute had just enough of its yearly catch quota left to embark upon one final fishing trip from Lerwick, before heading back to its home port of Fraserburgh, where it will tie-up until January.

Early in the New Year, the vessel will resume mackerel fishing once more for a few weeks before switching to herring off Norway, and then moving onto North Sea herring in home waters during the summer.

Sustainable harvesting is something close to both skippers’ hearts, and during my trip aboard the vessel, it was clear to see their continual interest and fascination in the varied marine life glimpsed from the boat.

Actively involved in research

Indeed, Scottish mackerel and herring fishermen are actively engaged in scientific research to increase our knowledge of stocks.

In effect, they are using their boats as research platforms where fish are sampled on a regular basis, with catch quantities, the location and the length and weight of the fish all being carefully recorded.

The results can be used in scientific assessment processes to ensure sustainable catch levels in future years.

We all recognise the importance of sustainable harvesting and the need for the fishery to be well-managed

Such work is spearheaded by Dr Steven Mackinson, a research scientist who is employed by the representative fishing organisation, the Scottish Pelagic Fishermen’s Association.

“We all recognise the importance of sustainable harvesting and the need for the fishery to be well-managed,” says Matty.

“The Resolute is a new boat and we have invested heavily in it, so it is in our interests to ensure our mackerel and other fish stocks stay healthy, ensuring that our fishing tradition can be passed down to future generations.”

On a personal level, I was left hugely impressed by this team of close-knit fishermen, risking their lives on a regular basis to put food on our plates.

They were like a band of brothers, working in harmony together and looking out for one another in the cold and often stormy waters of the north-east Atlantic in their quest for the sparkling shoals of fish.