James Joyce’s Ulysses is viewed as both a triumph of literary modernism and a very difficult book. One hundred years since it exploded on to the literary scene, we look at its enduring legacy.

A single day, three characters and a walk around Dublin. The premise may be simple but Irish literary giant James Joyce took his story of Leopold Bloom and intertwined it with Homer’s Odyssey, adding layers of historical and literary allusions, telling each episode in a different prose style.

He invented words as he went, and threw in an unholy measure of earthy humour and explicit language, leaving readers enthralled, appalled or confused.

A banned book

Written by Joyce during one of his periods of self-inflicted exile from his native Ireland, the novel was initially published in excerpts in the American magazine The Little Review in 1918-20. The controversial work was branded obscene and subjected to a legal ban which remained in place in the US until 1933.

Publishers in the British Isles took a similar stance and it fell to Paris-based Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company to print the book in 1922. A supporter of Joyce’s work, Sylvia reportedly had no patience for “the spectacle of ignorant men solemnly deciding whether the work of some great writer is suitable for the public to read or not”.

100 years on, the novel Ulysses and the genius of James Joyce are celebrated the world over – and the cause of much head-scratching for students of English literature.

The novel is no longer viewed as morally repugnant but rather inspires fans to make the pilgrimage to Dublin to follow in Leopold’s footsteps on Bloomsday, June 16 – the day on which Ulysses is set.

Taking part in readings, dressing in character and visits to places featured in Ulysses play a large part in the Dublin celebrations, while Joyceans all over the world commemorate the novel in their own towns and cities, often while sporting the hallmark straw boater hat.

Constant companion

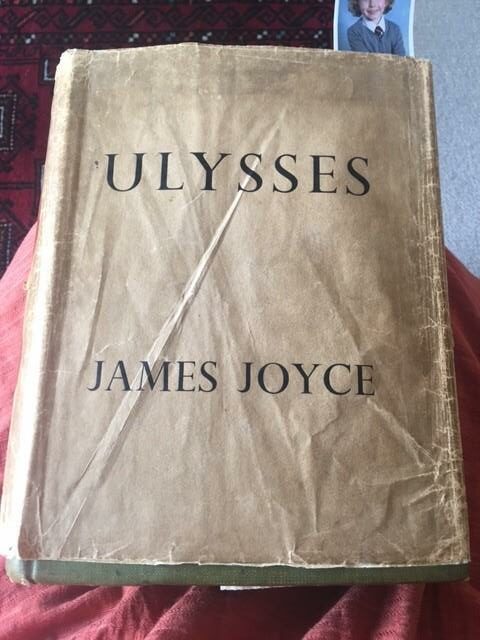

For Patrick Corbett, 86, the writing of James Joyce has been “a constant companion”. Dublin-born, Patrick has lived in Britain since the 1960s. His life-long passion for writing and plays never waned and he is the very proud owner of a special edition of Ulysses thanks to his daughter Joan Reid who purchased it after spotting it in a St Andrews charity shop window in 2008.

“I saw it and thought of you,” she says in conversation with her father.

Patrick clearly cherishes the tome, number 447 of the first English “Bodley Head” edition of 1,000 copies printed in 1936 – 100 of the books were signed by James Joyce and sold for six guineas each while the unsigned tomes cost three guineas.

His love of Joyce’s writing began with The Dubliners. “I travel with that book,” he says. “The book is dog-eared, falling to pieces and James Joyce has been a companion of mine for 40 years.”

A real treat

Of Ulysses itself, Patrick says: “I was happy to attempt to dive into it! I didn’t find it intimidating at all – it was a great privilege to have that edition, a great privilege to have Ulysses.”

“I particularly like the language,” he explains, opening the book to read its first lines: “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan,” he begins, skipping through the Latin “Introibo ad altare Dei,” before reading “Come up, Kinch. Come up, you fearful Jesuit!” with joyful relish.

“And on it goes,” he laughs. “I haven’t read it all. I have just dipped into it – it’s a real treat reading it actually. It’s a magical book – almost a sacred book to me. It’s huge and it takes some comprehending.

“I don’t think there is any other book in the English language like this, it’s just wonderful.”

Another Ulysses fan, retired bookseller Kean Young, divides his time between Scotland and Spain. He describes Joyce as: “My favourite author in the English language and Ulysses the greatest book of fiction I have read to date.”

Kean explains that he waited to read the novel on his retirement. “I was aware of the book for many years but decided to digest it when I could give it my full attention – this became a delight and something of an obsession.

Man with a plan

“I made a plan to research the author, and read his work in a chronological sequence. Having read Dubliners, I progressed to A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man. This work allowed me to then read and attempt to comprehend the plot and role of Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses. I was hooked.”

Like many readers, Kean is fascinated by Joyce’s love/hate relationship with his native Ireland and drawn to his characters. “Dublin and its characters at the beginning of the 20th Century was vividly portrayed by Joyce, warts and all,” he enthuses.

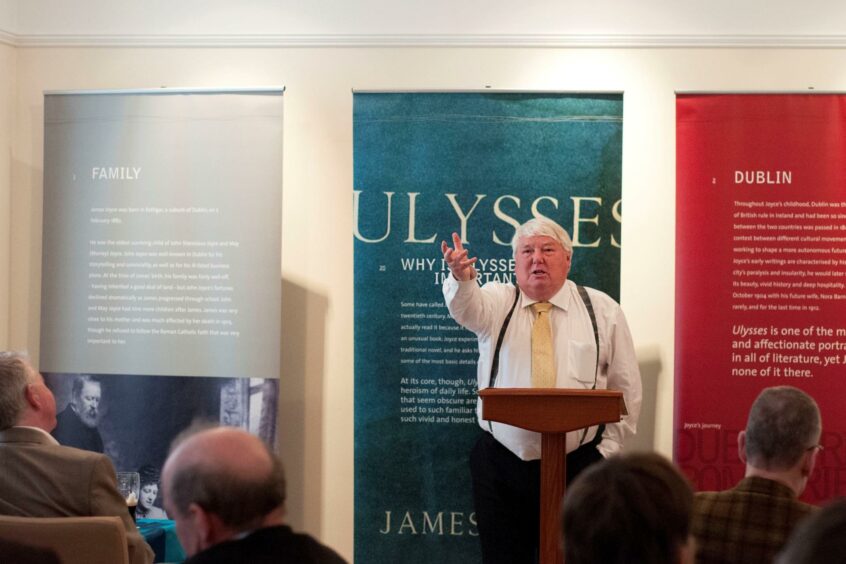

Dundee-born former BBC Scotland political editor Brian Taylor is one of Scotland’s best-known Joyceans. An avid reader from boyhood, he recalls discovering Ulysses as a result of that passion for the written word.

“While at school in Dundee, my interests ranged widely from sport, including fanatical support of Dundee United, to literature. I retain both to this day,” he says.

“However, even within the literary field, I spread myself somewhat. A young teacher at high school sparked an enthusiasm for the novels of Sir Walter Scott but I also admired Irish literature. Starting with the poetry of WB Yeats, I moved to Synge, Swift – and finally James Joyce. I have regarded Joyce as a genius ever since.”

Like Kean, Brian admits that “Ulysses can be challenging. Joyce teases us with literary and historical tricks and tropes”. He encourages us to stick with it, though. “Its subtlety, humour and intense narrative mean that it is decidedly worth the effort.

Conduits to Ulysses

“It’s perhaps best to start, as I did, by reading the earlier works, the Dubliners and A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man. They are outstanding in their own right, but also useful conduits to Ulysses.”

Brian recently chaired a discussion at the Scottish Storytelling Centre to celebrate 100 years of Ulysses. Introduced by fellow St Andrews University graduate and consul general of Ireland in Edinburgh Jane McCulloch, one of the themes discussed was whether Ulysses should be viewed as an Irish or a global novel.

Grounded in Dublin

“Ulysses is very much grounded in Dublin,” says Brian, “albeit with a framework derived from Classical myths and stories. Hence the title!

“However, I believe that it explores global themes such as passion, isolation, betrayal and common humanity. Importantly, with humour and empathy.”

Uncomfortable in his own country, Joyce lived abroad for most of his life but seemed incapable of writing about anywhere but Ireland in general and Dublin in particular.

“Joyce had what might be politely described as an ambivalent attitude towards his native Ireland,” says Brian.

“He found himself unable to live there. Yet it seems he could not write about anywhere else. It seeped into his consciousness and remained. So his narratives of Dublin are written, inevitably, from a distance.

“Yet I believe he took great care to be as accurate as possible in his portrayal of Dublin and Dubliners.”

For Jane McCulloch, growing up in Ireland meant that James Joyce was one of the literary greats always at the forefront of the national consciousness. Looking back, the consul general can’t pinpoint the first time she read his work. “I honestly don’t remember, but it was traditional to have a huge poster of ‘Great Irish Writers’ in the classroom. Those featured were, then, of course, all men – O’Casey, Yeats, Kavanagh, Joyce and so on,” she says.

“So, while the Irish canon of literature was always broader than that, and, is rightly celebrated as much broader than that now, there was no not knowing of Joyce growing up. I read Dubliners first, and it really is brilliant. It wasn’t foisted upon me, though, it was simply part of the rich literary tradition into which I could delve.”

False starts?

Like many people, Jane admits that she has started to read Ulysses countless times. “I have yet to finish it,” she says, “but I think that it is easy to be familiar with Ulysses without having read it completely. The language, the characterisation, Dublin as a character, the comedy, the pathos, the bawdiness… there’s more than enough to be drawn to, and there are elements of the story, or passages of the text, that are universally familiar.”

Jane also points out that although the book is viewed as an Irish novel, Joyce visited Scotland and developed an interest in Scottish writers, history and literary tradition.

“He visited Glasgow with his father in 1894,” she explains.

“The wonderful short story The Dead in Dubliners features a Scottish character, Mrs Malins. By the time he writes Finnegan’s Wake, Scotland, and Scotland’s literary traditions feature more and more.”

Enduring legacy

A century after it was first published in full, Ulysses may have lost its capacity to shock the modern reader but it continues to entertain and provoke debate.

For Jane, Joyce’s novel is still celebrated today “because it merits it! This modernist masterpiece transformed world literature. It was banned, it was burned, it was blacklisted; Joyce was blackguarded, and he blackguarded in return, so it is more than its text.

“The celebration of Bloomsday, June 16, the world over demonstrates how this book, set on just one day, June 16 1904, has caught and retained imagination the world over.”

And for those of us who are still to get to the end of the tome? “The podcast is your friend!” she says.

“It has long been advocated that the way to read Ulysses is to read it out loud. That’s fine if you have a room to yourself, or a willing companion who wants to hear it read.

“However, many brilliant readers have done that for us, and I am currently enjoying Ulysses with the book in hand, while listening to others’ voices. I can recommend the recordings which are being released by Friends of Shakespeare and Company in Paris, the original publishers of Ulysses.”

A short recording of an excerpt from Ulysses is being released every day until Bloomsday this year, read by an impressive cast of more than 100 writers, artists, comedians and musicians from all over the world including Will Self, Eddie Izzard and Amy Sackville.

The recordings can be found by searching Friends of Shakespeare and Company read Ulysses by James Joyce online or on your usual podcast provider.

From Dubliners to Ulysses

Another Scottish fan of Joyce’s writing is social media journalist Carla Jenkins, “I first came across him when my school English teacher, Brian Docherty (‘The Doc’ at the time) left us some battered copies of Dubliners on our desks one day in the approach to our highers,” she recalls. “I went to a Jesuit Catholic school and had realised a few things about my faith and the schools teachings at that time which I think led me to feel an affinity for the book and the characters.

“I haven’t quite pinpointed what it was about the books or his writing that hooked me in, but I just remember it being the most fantastically beautiful thing that I’ve ever come across. I had never experienced writing like it.”

Joyce Summer School

“I went from there to reading A Portrait, which was for school again, and I actually attended the Trieste Joyce Summer School without having read Ulysses. It took me a whole summer to read it, which was not usual to me, and I read it going between Glasgow to London to Dublin to Trieste and ended it in Portugal. I’m still convinced that part of me only read it because I had promised to write my University dissertation on it, but maybe I knew I needed that push to get over the line and carry about the huge big blue book with me on planes, trains, automobiles.”

For Carla, it is perfectly normal to feel intimidated by a tome of Ulysses’ reputation, in fact she feels that anyone who claims not to be may be slightly deluded. “Yes, I think that to say you aren’t intimidated by Ulysses is a really special type of lie,” she says.

Don’t start at the beginning!

But she does have some useful advice for anyone waiting for a way into the book, “Start at Episode 4,” she enthuses, “don’t be afraid to google what in the name of God is happening in this; read it out loud and roll the words around in your mouth, underline the sentences that you find beautiful and write them down.

“Ulysses is written for the reader to use and abuse as they please. It’s one of the greatest gifts that art has given us.”

So whether you choose to dedicate a summer to reading it, dip in and out at your leisure or let a podcast do the talking, all of these Joyceans would urge you not to give up on Ulysses – and most of all to enjoy it in the way that suits you best.

- For information on international events celebrating the centenary of Ulysses in person and online, visit ulysses100.ie and bloomsdayfestival.ie

- To watch Brian Taylor’s conversation with Scottish Joyceans Carla Jenkins, Maria-Daniella Dick and Richard Barlow online search The publication of Ulysses – a lively conversation in Edinburgh.

Conversation