For some youngsters, it was the Daleks that sent them scurrying behind the sofa. For me, it was the Robinson family’s robot in 1960s’ US sci-fi series Lost in Space.

I found the thought of a talking, comprehending machine horrifying and fascinating at the same time.

Fifty years later and robots are now an integral part of so many areas of our lives – with new technological developments being made every day they are increasingly finding their way into our homes, our workplaces and even our pocket, so it’s important to understand and shape the relationships between humans and machines.

V&A Dundee’s groundbreaking exhibition, Hello, Robot. Design Between Human and Machine opens today. With more than 200 objects to explore, it takes visitors through four stages of robot influence and evolution.

In the run-up to the exhibition’s opening, V&A visitors young and old were entranced by a bubble-blowing robot called Soap Opera. The former industrial robot was reprogrammed by Andrea Anner and Thibault Brevet of Marseilles-based AATB, who specialise in transforming industrial robots into playful installations.

“From the 17th Century bubbles have been a comment on the morality and transience of life, but most people just enjoyed it as a beautiful playful thing,” says curator Kirsty, revealing that Soap Opera produced more than 38,400 bubbles over the seven weeks it was on display.

“Robots are part of our everyday and not a moment goes by without new developments in robotic technology,” Kirsty continues.

“How and where we encounter robots, the sort of relationships we form with them, and how we interact with them – or they with us – is no longer the exclusive domain of engineers and IT experts. Designers are now often at the centre of these decisions.

“This is an exciting time, and the right moment to be asking big questions about the role robots should and will play in all our lives.”

The idea of automata originates in the mythologies of many cultures around the world, while the word ‘robot’ comes from the Czech word, robota, meaning forced labour.

Hello, Robot. is laid out in four distinct themed sections, each asking thought-provoking questions about our relationship with robots. The first section focuses on the science and fiction of robots, tracing our fascination with artificial humans and looking at how popular culture has shaped our feelings about them.

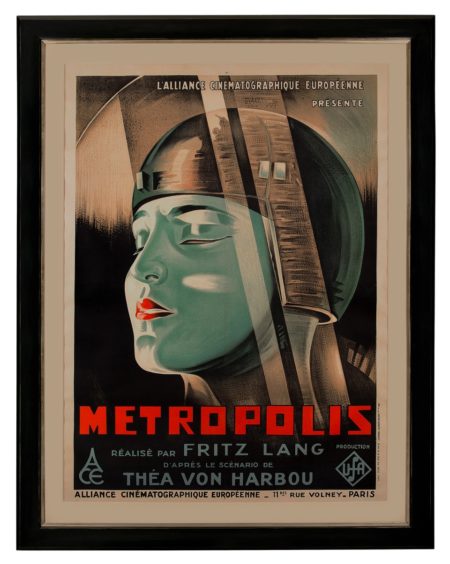

It includes a Japanese directional robot; an original film poster from Fritz Lang’s epic film Metropolis, which features one of the first robots ever depicted in cinema; the R2-D2 film prop which appeared in first Star Wars film in 1977; and the Robots of Brixton film which predicts a dystopian future where robotic workers battle with police in scenes reminiscent of the Brixton riots of 1981.

“These first four objects all explore the science fiction of robots and invite visitors to think about their first experience of a robot,” says Kirsty. “For most of us it was through popular culture, magazines and comics and TV. As well as giving a contextual understanding of what robotics are, this section also explores the research people are doing into robotics and challenges our perceptions of the relationship between humans and robots.”

While the first section looks at the two extremes of opinion – do robots help or destroy – the second phase of the exhibition then delves into the world of industry and work, looking at the impact of robotics from several different perspectives.

“It’s a pertinent and incredibly sensitive subject,” Kirsty reflects. “As well as exploring the idea that robotic technology poses a threat to jobs, it also looks at how robots can create opportunities, questioning the difference between work that can be automated and human creativity,” says Kirsty.

Here, visitors can meet the first collaborative robot designed to work side-by-side with humans in factories and a scribe robot called Manifest, programmed to write manifestos.

“I love Manifest,” Kirsty smiles. “With eight dictionaries in its internal memory, it churns out manifestos which don’t make sense and if it does it’s completely by chance. While asking if robots be creative, it also makes the point that they’re still far from perfect and a long way from taking over.

“This section looks at the relationship between humans and robots going forward and concludes that while the future looks optimistic and collaborative in the main, there’s still very much a place for both of us. Humans provide the creative side while robots carry out the repetitive side of things.”

The third section shows how humans are increasingly coming face-to-face with robots as household helpers and digital companions.

“At this point we are asked to consider if we are willing to become dependent on smart helpers, if objects can have feelings and to what extent robots can replace humans in social contexts,” says Kirsty.

The objects in this section, which include an industrial robot adapted to feed babies and drones redesigned to look less threatening, aim to encourage conversations about the relationship between humans and machines at a time of fast-paced technological advancement.

“This section is all about our emotional attachment to robots and how we feel about them caring for us either now or in the future,” she says. “The objects are a good mix of those already in use and others that are speculative and still at the research stage.”

Paro is a therapeutic robot modelled on a baby seal, created in 2001 by Takanori Shibata, and used in more than 30 countries – including the UK – to provide comfort to elderly people and patients suffering from dementia.

As well as being designed to look cute, it contains different kinds of sensors so it can react to light, sound, temperature and touch, cooing and purring while being petted, tracking movement with its head and eyes, and remembering names.

“The fact that it is a seal rather than a cat or dog is deliberate – it won’t remind people of a beloved pet they have lost in the past,” explains Kirsty. “Used by the NHS, Paro is an example of robots taking care of us.”

Another thought-provoking exhibit is Raising Robotic Natives created by Stephan Bogner, Philipp Schmitt and Jonas Voigt in 2016.

A speculative design project, it imagines an environment in which children are exposed to constant robotic interactions.

“The Baby Feeder installation explores how much automation we consider desirable and questions if we should let robots replace humans in activities that we consider to be intimate,” says Kirsty. “The Baby Feeder toolhead fits a standard baby bottle and would save parents between 15-30 minutes per meal.

“This object works in two ways – it talks about children being used to robotics from birth and makes us question the ethic behind robots taking care of children: is this something we want?”

Kip, created in 2015 by Guy Hoffman and Oren Zuckerman, was developed to increase people’s awareness of their behaviour by detecting and reacting to the ‘tone’ of a discussion. The robot uses physical, non-verbal gestures to respond to sound. If the tone is friendly Kip leans forward and shows interest. However, if the tone is aggressive it draws back and begins to tremble.

“The designers hope prompting people to feel empathy for Kip will encourage more positive verbal interactions between humans,” says Kirsty.

“Kip is really sweet and when I saw it in Lisbon, a group of teenage boys surrounded it and it was fascinating to see how conscious of their actions they were and the power they had over its ‘emotions’.

Friend 1 is part of the Making Friends by Making Them series by designer and engineer Dan Chen. This desktop robot senses stress levels by monitoring activities and offering comfort by patting your hand with a gentle moving arm. It has also been programmed to say: “It’ll be all right”.

“Dan’s projects are very speculative and interesting and this series asks how we feel about a robot comforting us rather than a human – can robots convey comfort the way friends and family can?”

The final section of the exhibition examines the blurring of the boundaries between humans and robots, from hi-tech fashion that can sense danger and put up a physical barrier to the idea of robotic architecture and smart cities.

“It looks at the convergence between humans and robots and how our lives have already come together in fashion, architecture and medicine and other fields that you might not have considered.

Key items in this section include Spider Dress 2.0 – Dutch hi-tech fashion designer Anouk Wipprecht explores how automation and robotics can influence wellbeing by creating technological couture. Microchips, sensors and LEDs are integrated into her fabrics which she makes with a 3D printer with the result that her designs move, breathe and react to the environment around them.

The dress also registers the speed with which someone is approaching – the multi-jointed, movable robotic spider legs attached to the collar of the dress reach out if someone gets too close.

Outside the exhibition visitors can enter for free a new large-scale structure called Up-Sticks specially commissioned for V&A Dundee. Twisting and curving along the gallery, it’s inspired by historic Scottish building techniques and made of wooden planks and timber dowels.

Constructed in Gramazio Kohler’s robotic laboratory in Zurich it tests the idea of creative collaboration between human and machine. Abertay students from the Masters in Professional Game Development course have also created an augmented reality (AR) app which will be pre-installed in iPads available to visitors to use in Up-Sticks.

“AR enhances the spirit of the object through technology – it reveals hidden animation and visual effects to make the objects arresting and informative and show how they were made,” says Professor Joseph de Lappe, who led the research project.

Before she heads off to make the final tweaks to the exhibition, Kirsty has the final word.

“Hello, Robot. is a really important story to tell and fits in perfectly with V&A Dundee’s ethos as a museum of design. The exhibition explores how robots affect lives for good or bad, takes these themes and develops them further.

“It will be really interesting to see visitors’ preconceptions challenged and the dialogues that come out of this.”

Hello, Robot. Design Between Human and Machine starts today November 2 and runs until February 9 2020.