The second in an exclusive four-part Courier serialisation of renowned Scottish writer James Robertson’s biography.

Michael William Marra was born in Dundee on February 17 1952, the fourth of five children: Edward, Mary, Nicholas and Michael were all born within four years of one another; there was nearly a five-year gap between Michael and Christopher. Their father, Edward Marra, was a printer. Michael recalled, ‘He worked a Heidelberg cylinder, the proper old letterpress printing’, which puts a slightly romantic gloss on what was often mind-numbingly tedious work.

Their mother, Margaret (née Reilly), was a primary school teacher, although she stopped teaching for several years in order to look after a house full of young children. Margaret was one of six children herself, and her family had struggled to find the means to enable her to go to teacher-training college at Craiglockhart in Edinburgh. Michael would celebrate her achievement on his album On Stolen Stationery with the track ‘Margaret Reilly’s Arrival at Craiglockhart’.

Lochee, where the family lived, was and is a working-class district, with a long history of immigration, especially from Ireland but with significant numbers also coming from Italy and Poland. This helped to create a diverse and vibrant culture.

The singer Sheena Wellington was raised in the same area of Lochee as the Marras, Clement Park, and remembers it as a good and safe place to grow up: the houses had their own bathrooms, and coal fires with back-boilers to heat the water; children played in the middle of the street because nobody owned a car; everybody used the bus.

Sheena and her wee pals used to chap the Marra door and ask if they could ‘take the bairn oot’. ‘Mind you, we very rarely got to take him oot, because we were very rarely clean enough. Mrs Marra being a teacher, if you had the slightest hint o’ a cold or if your nails werenae perfectly clipped, you didnae get!’

-

For more from the series, click here

But Sheena also acknowledged the very positive influences of Michael’s upbringing: ‘The family itself had a faith, an ethic, and a working-class decency which Michael grew up with…. He knew what was right, what was wrong, and in the middle was compassion and I think that very much came from his background.’

Both Michael’s parents had a great appetite for music, which was part of daily family life: Margaret played piano and sang in choirs; Edward did not play an instrument but loved jazz and classical music. Duke Ellington and Ludwig van Beethoven were Edward Marra’s great heroes: the only time Michael ever saw his father combing his hair was the night he went to see Ellington and his band play the Caird Hall in 1967.

One feature of the household, an item which in time Michael would inherit, was a very fine Blüthner piano. Michael’s oldest brother Eddie learned to play on this instrument and passed on a few tricks to Michael. Michael learned mostly by ear and by accident, discovering ‘the good stuff’ through perseverance: ‘I love the shape of written music, but it looks like an adventure with Neptune rather than what [the notes are] supposed to convey. To me, the piano is all lying in front of you. It’s difficult to make a mistake as everything leads to something else.’

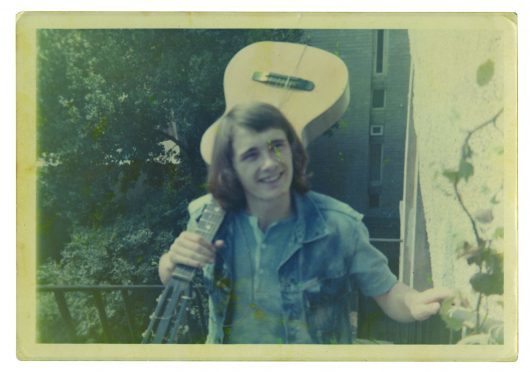

When Michael was in his teens, Eddie brought home a guitar for him and Chris. Both of them were interested in learning how to play it, taking their cues from the likes of James Taylor and Joni Mitchell. But while Chris would become a professional musician, for Michael instruments were always only a means to an end; and the end was to write songs.

Michael absorbed everything, from hymns sung at church (the melody of ‘Soul of My Saviour’ would find its way into the opening bars of Michael’s ‘Mother Glasgow’) to Elvis Presley – ‘Jailhouse Rock’ was his earliest, indelible musical memory. The Beatles impressed not just because of their energy and enthusiasm but because they wrote their own songs. In fact, Michael said, it was John Lennon who ‘forced’ him to be a songwriter: ‘his voice was more than language.’

Michael first publicly articulated his long-term ambition to write songs while still at St Mary’s Primary School in Lochee. A group of boys in his class were discussing what they wanted to be when they grew up, and he said he wanted to be a songwriter. As the others mostly intended to have glittering football careers, this was not a popular option, in fact he expected derision, but then another boy, John Duncan, chipped in, ‘My uncle’s a songwriter.’ This assertion too was met with a degree of scepticism. ‘Oh aye. And who is he?’ ‘Stephen Sondheim.’

None of them had heard of Sondheim or West Side Story (the show opened on Broadway in 1957), but it turned out that John Duncan was telling the truth. ‘The mere fact that somebody had a relation who wrote songs as a job was impressive,’ Michael remembered. ‘It was a big thing for me.’

Michael and school

It is fair to say that Michael and school did not agree. Once, at primary school, he was pulled up when writing a story about meeting Cilla Black on a bus in Lochee. He had written a piece of dialogue in which a bairn said, ‘Look at her, she looks dead like Cilla Black.’ The teacher red-lined the sentence and replaced ‘dead’ with ‘very’. From then on, there was always likely to be trouble between Michael and the system.

But it was at secondary school – Lawside Academy – that things became really difficult. His disaffection was less with learning than with school as an institution, and this would grow into a lifelong distrust of all institutions. His extreme antipathy to being told what to do and when to do it would re-emerge twenty years later when he found himself kicking against the demands of the music industry. ‘I really do not like anybody controlling my time or even deciding what topics we are going to be thinking about. That, very early, was a drawback at school.’

By his own admission he was every teacher’s worst nightmare, an ‘underminer’ quietly and deliberately sabotaging everything he could. There was, for example, the occasion when he persuaded his classmates to bring an assortment of screwdrivers and other tools into school: under his direction, they proceeded to dismantle the classroom, taking the desks apart but leaving them with just enough support to stay upright until the next class arrived and tried to sit down.

‘It wasn’t as if I wasn’t educating myself anyway,’ he said later. ‘I could read and write.’ He could, for example, consult the encyclopaedia his father had at home. ‘They taught us at school about the discovery of the South Pole without mentioning Amundsen. That told me what was going on quite early, I thought: “Watch out.” In my book at home, A was for Amundsen.’

Michael and rules

One of Michael Marra’s abiding characteristics was a distrust of institutions and officialdom. School, church, the monarchy, the music industry and the BBC all fell into this category. When he was musical co-director, alongside Rab Noakes, of John Byrne’s TV series Your Cheatin’ Heart, he spent nearly a year based in BBC Scotland’s Glasgow building and said he felt as if he was working in a post office. Rab said of Michael’s earlier, stressful experience of being in London, ‘There’s a way you have to act in the music industry and it’s difficult for many people but for Michael in particular it was hard, he just couldnae connect at that level, that kind of language and behaviour.’

Michael reacted badly to rules and regulations. If you tried to tell him what to do, he would often do the opposite. His brother Chris said, ‘Michael felt failed by school, but school didn’t fail him – he just didn’t suit it. It’s like saying that showbiz failed him – it didn’t, it just wasn’t his place.’

Independence of mind and freedom of choice were fundamental principles for Michael, from when he was a boy right through his entire adult life.

Michael Marra. Arrest This Moment is published by Big Sky Books and is available from October 20 via all the usual stockists or direct from www.bigsky.scot. £16.99 for paperback, £24.99 for hardback.

Michael Marra. Arrest This Moment is published by Big Sky Books and is available from October 20 via all the usual stockists or direct from www.bigsky.scot. £16.99 for paperback, £24.99 for hardback.