AMONG the great treasures of the British Library are the Thomason Tracts, a remarkable collection of 17th Century Civil War-period printed pamphlets and news-sheets.

Numbering around 22,000, these were collected by the London bookseller George Thomason at the time of their issue.

While researching Cromwellian history at the London library some years ago, leaning heavily on the tracts allowed me access to the collection’s treasures, including rare pamphlets dealing with the trial and execution of Charles I in 1649.

The English Civil Wars took their time to gain momentum. As the pace of mobilisation quickened, Oliver Cromwell was busy in committee work to increase parliamentary power. Conciliation with the king seemed a distant hope and Cromwell’s work was, in effect, the early preparation for the conflict to come.

By the spring of 1642 he had just fashioned an achievement in the Long Parliament, the Militia Ordinance, legislation which positioned the army in the hands of those who would protect Parliament against royalist forces, and which placed sovereign authority in Parliament’s hands.

As the Civil Wars unfolded, the private correspondence of the king added to Parliament’s resolve. The letters of foreign ambassadors at Charles’s court proved the king intended to re-establish his authority in England with foreign help and by force.

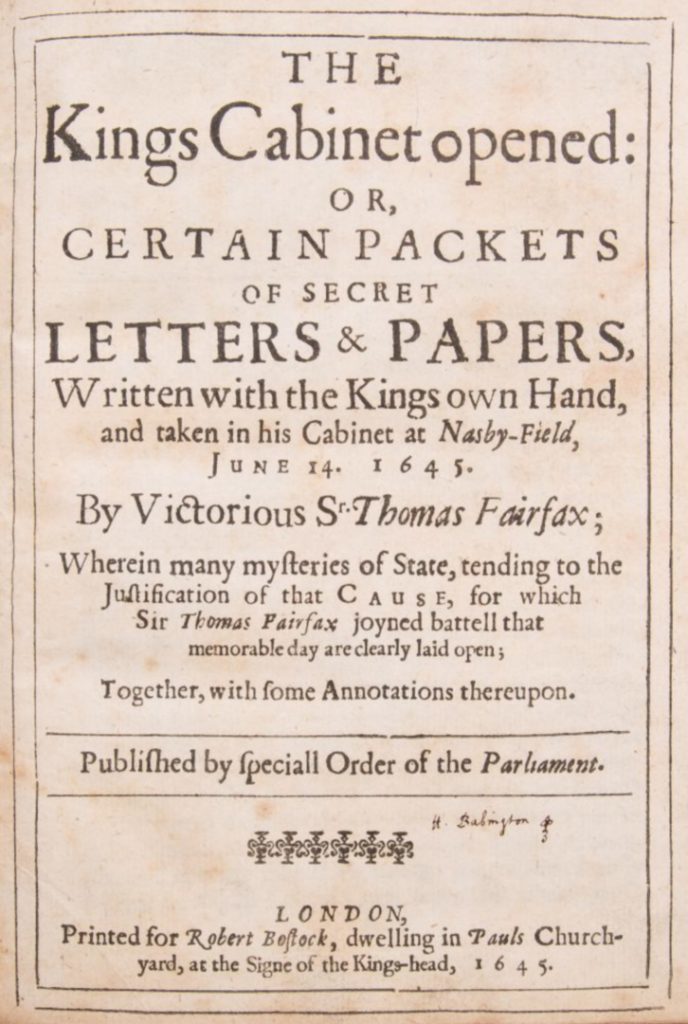

And then, after the Battle of Naseby in 1645, Charles’s own letters were seized by Roundheads and sensationally published as The King’s Cabinet Opened, confirming his wily intentions beyond doubt.

This discovery comprised private copies of the king’s letters, and original letters sent to him. It included 20 letters from the king to Queen Henrietta Maria, and five from her to him. A huge scoop in today’s terms, they were quickly published to demonstrate the king’s double dealing.

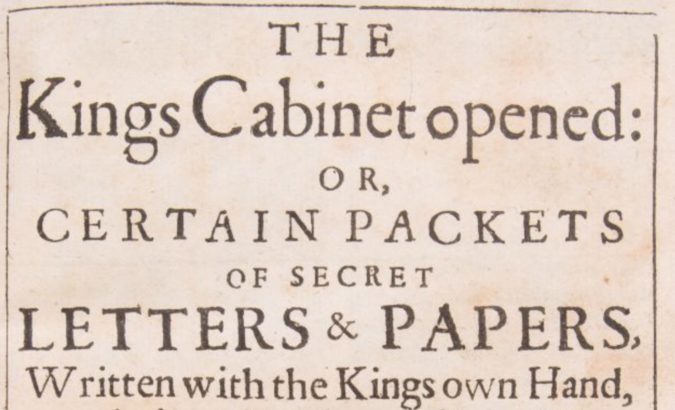

Bearnes Hampton & Littlewood’s sale in Exeter on September 6 sold a copy of this important work – The Kings Cabinet Opened. Or, Certain Packets of Secret Letters & Papers, Written with the Kings Own Hand, and Taken in His Cabinet At Nasby-Field, June 14. 1645.

Published in London and dated 1645, the BH&L copy was in decent condition and bound into 56 pages.

Not a rare work, but history-changing nonetheless, it sold for a triple estimate £280.