The Angus Glens as we know them today are a near wilderness inhabited mainly by deer and grouse.

Farmhouses and hotels are sporadic enough for this area to be a reserve for solitude, escape and country hikes well away from urban areas.

It may be hard to imagine, then, that these glens – Clova, Isla, Prosen, Esk, Moy and Lethnot – once teemed with thousands of people.

For centuries until the 1800s the residents lived in townships, the remnants of which can still be seen in even the remotest areas.

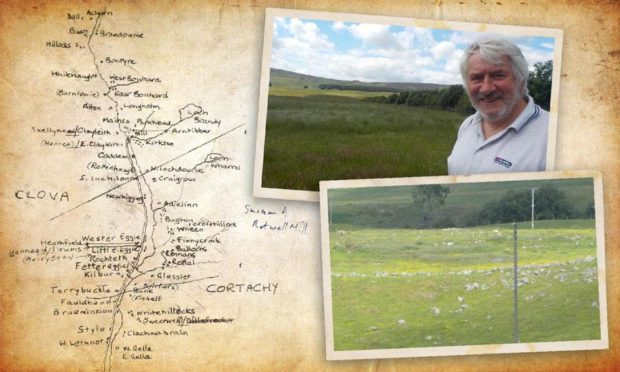

Some years ago, Kirriemuir farmer and local historian David Orr joined other amateur archaeologists to investigate deserted rural settlements dating back to the medieval period.

The group was formed under Scotland’s Rural Past Scheme, run by the Royal Commission on Ancient Monuments of Scotland, which was concerned about the disappearance of medieval ruins.

Here, David reveals its illuminating findings on Glen Clova’s past, and explains how a war and changes in rural and urban industries contributed to its declining population.

‘There was something like 1,200 people’

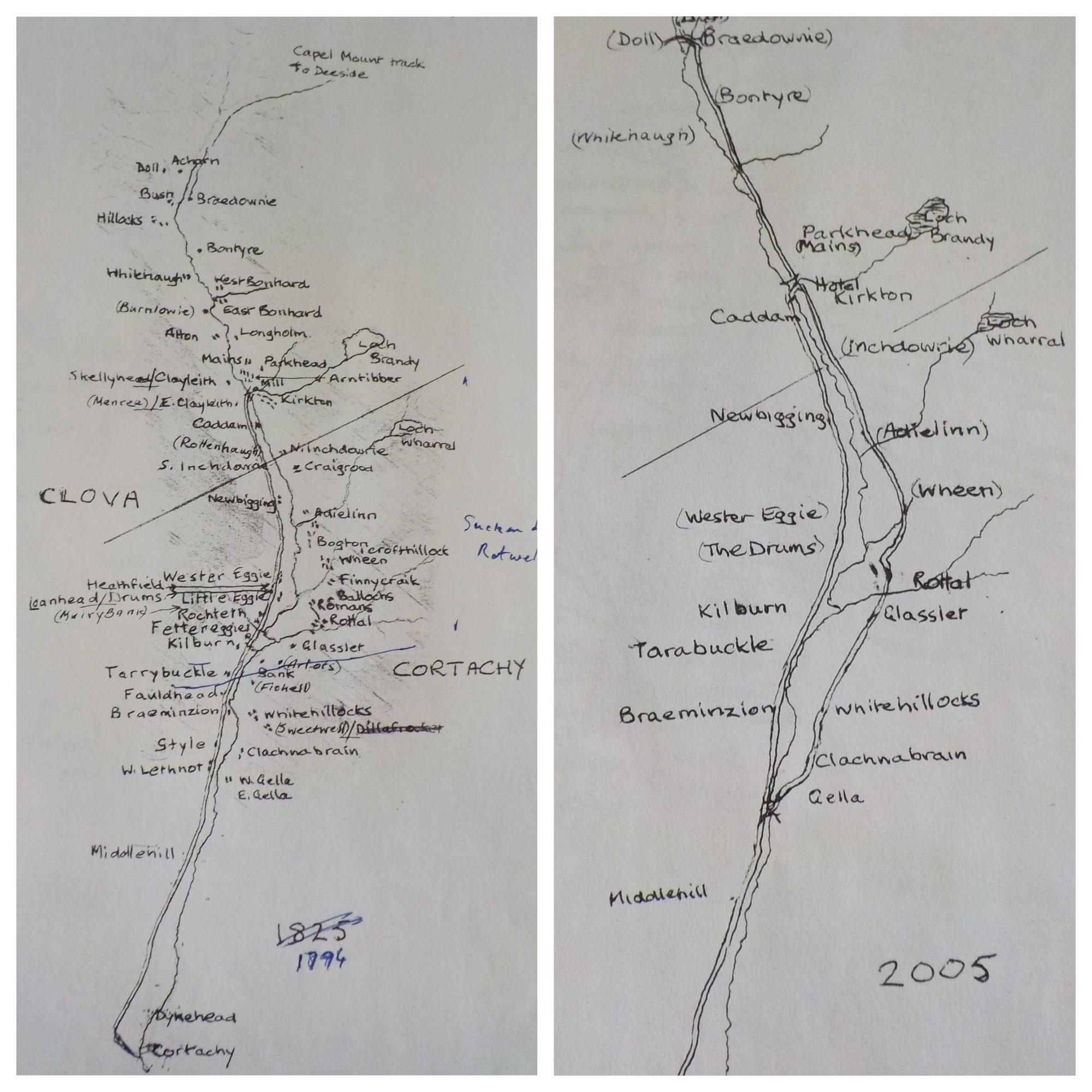

Hand-drawn maps compare the glen in 1794 to 2005.

The map on the left from 1794 shows several populated townships that no longer exist. These include Bogton, East Bonhard, West Bonhard, Style and Finnycraik.

The 2005 map on the right includes many fewer residential locations.

David says: “Going back to around 1500 to 1600 there were far more people living in the countryside and in Glen Clova there was something like 1,200 people. Now it’s less than 40.”

Sources of information

- Factual sources: Airlie estate papers (GD16 in the National Archives) and the Balnaboth papers (with Hector McLean of Balnaboth).

- The parish register of marriages and baptisms is extant, with blanks, from 1662, the Kirk Session minutes likewise.

- Available censuses detail the population between 1841 and 1901.

- Archaeological evidence

Very little is shown in Ordnance Survey maps. When these began in Scotland in the 1840s a decision was taken not to record everything in the landscape. A rule of thumb was that anything below knee-high would not be recorded.

‘People lived hand to mouth’

The group undertook a detailed investigation of Rochteth, a former township south of The Drums on the western side of what is now the B955.

Rochteth is first recorded in 1698. Kirk Session records state that in the 18th century action was taken to relieve poverty amid begging and famine.

“People lived hand to mouth,” says David.

“Their meals would have been based on oats. They would have had some milk from the cattle they kept, and some vegetables they would have been able to grow on their kailyards.

“It was not a monetary society. Rent was paid in fowl or sheep.”

Power of the miller

In this period the then Earl of Airlie owned great swathes of land in east Scotland, including the Angus Glens.

This meant all residents were tenants, mostly living off the land.

They grew grains such as wool, barley and linseed for flax and the fortunate ones may have had a cow or horse.

“It was subsistence farming,” David says. “They had to take grain to a miller to grind into porridge or suffer penalties such as losing their holding.”

The miller was one of the most powerful people of the community. Appointed by the baron, the miller would allocate the food “so you had to be on his good side”, says David.

There were two mills in Glen Clova. One was next to the hotel at the top of the glen. The other was in Rottal, requiring a traipse across the valley for Rochteth residents.

Countryside looked different

From the 17th to 19th century there was also a network of droving routes developed for people to get their animals to markets. They were sold in central Scotland and then driven again to England.

“The crops used back then were different to today,” says David.

“A lot of the residents weaved flax and wool. They grew a lot of flax at the bottom of the glen and the countryside would have looked very different to how it does now.

“In the summer it would have been a sea of blue flowers, which would have been quite a dramatic sight compared to the grass we have today.”

Living with animals

For thousands of years residents lived communally in roundhouses.

These circle-shaped buildings were made of wood and stones.

“Animals would have stayed inside because they kept you warm in the winter,” says David.

These homes were replaced during the Dark Ages (500 AD – 1550 AD) with Pitcarmick-type buildings that had rounded ends to break the wind better. They were more secluded but still lacked windows.

Apart from hut circles of indeterminate age the only remains of the townships are the remnants of these homes.

These can be spotted sporadically throughout the glens as two-foot-high turf-covered walls with roundel corners.

‘There was a village green’

David returned to Rochteth this summer to inspect the remains.

“Some sites have had ploughs put through them and the remains destroyed,” he says.

“Sites are disappearing fast but this site has been planted with trees and wherever you look you can see the footings of old buildings.”

“Houses all had a kailyard to themselves to grow food.

“In Rochteth there was a sawmill, kiln and village green.

“We know there was a shopkeeper and carrier who may have brought goods from Kirriemuir and may even have gone across to Deeside.

“The people who lived here worked the land and we can see where the chickens were kept.”

A circle is ‘not coincidental’

David also has some advice for those who might want to visit the glens on a township-spotting mission.

“Trees are tell-tale signs of old townships,” he says. “If you see one on its own it may have been next to a village green.

“Wherever you look you can see the footings of old buildings. If you see a square formation of laid rocks that will not be natural so you know it will have been a settlement.

“You’re always going to have rocks lying about but if there is an alignment or a circle then that is not coincidental.”

War effect on population

In 1740 Glwn Clova’s population had dwindled to 912. By 1841 there were just 250 people left. Twenty years later the glen was all but deserted.

The population dwindled for a number of reasons.

The glens supplied men to fight during the Jacobite rising of 1745, which was the first opportunity for residents to experience different areas.

“Things were never going to be the same after that,” says David. “Some died and some decided there was more to life than what they had experienced at the glen.”

Living conditions were also becoming harder. A trend towards intensive sheep farming persuaded the landowner to remove tenants or move existing ones to the fringes, effectively destroying their livelihoods.

This coincided with the beginning of the industrial revolution and the development of the jute industry in Dundee.

The population of the city grew from 4,135 in 1831 to 55,338 in 1841. Many of these new residents came from the glens, never to be replaced.

‘Covid has reversed the trend’

Today the Glen Clova population is a fraction of its former size and the old families – the Lindsays, Ogilvys, Duncans, Crightons and Mitchells – have largely gone and most inhabitants are recent arrivals.

“It’s difficult to say this is sad because it is how Scotland evolved,” says David.

“Covid has reversed the trend to a certain extent and for the first time in a couple of centuries more people want to live in the countryside.

“I like to imagine the busy scenes, particularly in September and October when huge numbers of cattle were driven to the markets.

“It was once a thoroughfare that now is very very quiet.”