How can market towns be resilient and sustainable to all in the 21st century? A recent lecture by St Andrews University’s Professor Sir Ian Boyd explored the ‘big picture’, writes Michael Alexander.

In his introduction to the recent Cupar & District annual lecture, Bill Pagan, chairman of Cupar’s Development Trust, noted that in the past half century, the market town and former royal burgh had been through many changes.

The former Fife county town had suffered the closure of its civil and criminal courts, its GCHQ facility at Hawklaw, Scotland’s only sugar beet factory, a major agricultural market, elements of its further education college and its status as a local authority headquarters.

During Covid-19, Cupar had proven itself as a “caring community” through collaboration by numerous local organisations, all determined to play their part in mitigating the problems caused by the pandemic, then contributing to recover from it.

In an ever-changing world, however, how does a vibrant market town like Cupar adapt to the environmental, sustainability and post-Covid challenges of the century ahead?

Looking to the future

The question was posed as guest speaker Professor Sir Ian Boyd gave an online lecture titled: “Environmental shocks and resilient communities: How a 21st century market town can be sustainable to the benefit of all’.

A Fellow of the Royal Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Professor Boyd was Chief Scientific Adviser at the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs from 2012 to 2019, and is currently Professor in Biology at St Andrews University where he leads on climate change.

An expert on environmental shocks and resilience, Professor Boyd admits he doesn’t know too much about communities and market towns. He brings a “very analytical perspective” because he’s a scientist.

But one of the “great strengths” of some of the things he’s involved in is they mix up physical and social sciences and come to joint conclusions.

Building resilience

Many of the principles that can be used to build resilience into communities apply as much at national and international level as they do at local burgh and individual household level, he says.

Professor Boyd explained that one of the functions he had in government was to take a “broad brushed view” of the 10, 20, 30 year future – something that few in government tend to do when they are “firefighting” and dealing with short term issues.

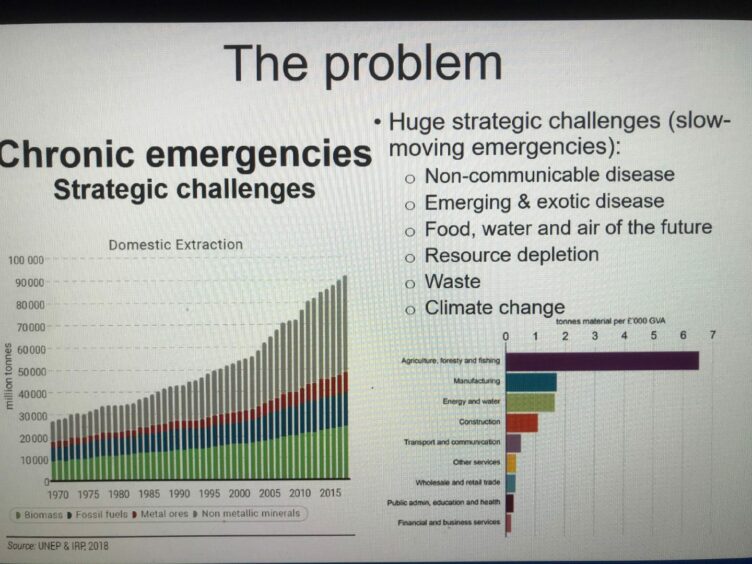

What are the strategic challenges?

What are the strategic challenges?

Non-communicable disease:

One of the biggest concerns of the health and science community right now is non-communicable disease, driven by lifestyle.

It’s illustrated by obesity and associated diseases.

It raises fears it will “swamp” our health system if it isn’t brought under control.

“That requires a whole attitude change and values change within society,” he says.

Emerging and exotic diseases:

However, the second example, illustrated over the past two years by Covid-19, is emerging and exotic diseases.

While a pandemic was an “entirely predictable event”, the timing and form of the disease was not known.

It was “rather fortunate”, he said, that relatively speaking, Covid-19 “didn’t kill very many people” because there are a lot of other diseases out there that could have killed much larger numbers and would have been much more difficult to manage.

However, it’s a continuous issue that needs to be addressed.

Food, water and air of the future:

Also of concern is access to food, clean water and clean air.

Most take them for granted. But he emphasises that they should not be.

“Our food supply system is extremely vulnerable to shocks,” he adds.

“During Covid-19 it was one of the biggest concerns that the food supply system would fail. It didn’t, but it was a close run thing on occasions.”

Resource depletion:

Another area of concern is resource depletion.

While these issues can often feel remote, the exponential extraction of resources for domestic consumption has been ongoing since the industrial revolution and is accelerating.

Professor Boyd says many don’t understand that some of our biggest environmental problems are actually associated with consumption.

Waste:

Waste is another major problem and a reality of the resources we consume.

Fundamentally, the rise in waste that we have – whether solid or gaseous like greenhouse gases and the pollution it causes – is driven by the amount of materials we absorb into the economy.

To give an illustration how fast it is going up, from the years 2010 to 2013, China used more cement than the USA did in the whole of the 20th century.

“With regard to waste, the amount of waste we produce is directly driven by the amount of material we consume,” says Professor Boyd. But waste is becoming toxic within the environment.

“And that toxicity expresses itself in a very wide range of different ways – everything from the poor air quality we have to global warming, climate change, to things like poly saturated hydrocarbons that leak into the oceans. They are very toxic, partitioning into the fats of tissues of things like fish.

“If you go onto the Department of Health website, it says don’t eat fatty fish more than once a week. The reason for that is actually eating it more than once a week you would potentially gain a toxic dose of some of these compounds.”

Climate change:

The final point on Professor Boyd’s list is climate change. It’s a consequence of consumption, but its consequences also have to be directly managed as well.

Examining how materially efficient different sectors of the economy are, Professor Boyd says agriculture, forestry and fisheries are “extraordinarily inefficient”.

Food production in particular is four or five times less resource efficient than manufacturing and energy and water, he says.

“What’s more,” he adds, “the real concern here is while manufacturing, energy and water are continually showing efficiencies – in other words they are becoming better at using less and less resource to get the same value, agriculture is not.

“It has not increased in its efficiency for the last 30 years, despite the fact that immense spent on research to do that.

“That’s why one of my big clarion calls is we have to transform how we produce food.

“If we do not transform how we produce food and do it quickly, probably by the middle of the century, then we will suffer a huge consequence because the land that we use for producing food cannot be used for other things, and that includes storing carbon, biodiversity and it also includes the health and welfare of people.”

How do we tackle the issues?

When it comes to tackling these fundamental issues, Professor Boyd says there are three competing discourses running through society.

The Tragedy Discourse:

The ‘Tragedy Discourse’ takes the view that unless global common land is managed properly, it gets “trashed”, as is happening globally now.

Backed by the likes of Greta Thunberg, it concludes that if we continue following that course, we will not only run out of resources, we’ll run out of living space for people too, and there will be serious winners and losers.

“Even in Scotland we use twice the amount of basic resource that we would be using if we were sustainable,” he adds.

“We use 18 tonnes of basic materials a year individually in Scotland, but we need to get that to eight tones to be sustainable.

“In other countries, particularly the USA, consumption is twice or three times what we consume in Scotland.

“But we shouldn’t make us feel good because we are well over what we are due as our fair share of global resources. It’s a values based argument, that literally how we live is not compatible with sustainability of the planet.”

The Adaptation Discourse:

The Adaptation Discourse, by contrast, is usually proposed by liberal economists because what they espouse is that we are an imaginative organism with fantastic powers and capabilities who can solve problems by ingenuity.

Examples might range from the Covid-19 vaccine to new food production technology.

The Survivalist Discourse:

The final discourse, meanwhile, is the Sustainability or Survivalist Discourse, which is more or less “business as usual”, with a few investments here and there.

“Most of the governments who attended COP26 are very much in this category,” he says.

“We’re not going to change how we live. We will invest to some extent in the technology that might dig us out of the hole. That’s very much the attitude in government.”

Acute emergencies

Professor Boyd has also been involved in planning for acute emergencies.

He had responsibility for the clean-up of the Salisbury novichok poisoning and has also been involved in other emergencies like flooding.

Systems are in place to respond to national risks when they occur and a continual process of understanding where those risks are.These range from pandemics to food supply failure to seismic activity, nuclear accidents and dam bursts.

Ultimately, however, the aim is to reduce the frequency and impact of events by creating resilience in communities.

“In other words, when things go wrong, then communities ideally will not even notice, and if they don’t notice then they are resilient” adds Professor Boyd.

*The Cupar & District lecture 2021 can be viewed below: