The winner of the fifth Dundee Burgess charity short story competition is St John’s RC High School pupil Lewis Neilson.

Third-year pupil Lewis was picked unanimously by judges for his short story Gold Digger.

Shortlisted competition entrants attended a special prizegiving ceremony in the City Chambers, hosted by the Lord Provost Ian Borthwick.

Participants from all of the schools in the city boundaries were eligible to take part and had to write a short piece of prose, 650-800 words in length focused on a particular theme.

This year the competition entries had to involve a character born into a close-knit family living in abject poverty. As part of the plot, a part of the family suddenly comes into a fortune, with the youngsters then having to explore how the fortune was acquired and whether the dynamic within the family changed.

Competition judge Catriona MacInnes, acting editor of The Courier, said Lewis and his fellow contestants produced stories of a very high quality.

She said: “This year’s competition was of an exceptional standard. The pupils really got to grips with the storyline and they are all to be congratulated.

“It was so tight that my fellow judges and I had a tough time deciding the order of the top three – there was a great deal of debate and discussion, but in the end it was a unanimous decision.

“The winning entry stood out because it really painted a vivid picture and the ending was perfect. Lewis should be really proud.”

Lewis and runners-up Emily Crawford and Lucy Johnston will all enjoy a tour of The Courier offices at Meadowside, as well as having their stories published on our website (see below).

Mr Borthwick, who handed over the prizes at Wednesday’s celebration, said the city should be proud to have so many talented youngsters.

He said: “Congratulations to all the winners who have done such an impressive job.

“Some of the stories were quite moving and you could tell they had all put a tremendous amount of effort into their work.

“Thanks are due of course to their parents, carers and teachers who have supported them in their endeavours.

“Each story was written to a very impressive standard and it was good to see they had such a good grasp of language and history.”

The Burgess charity was established in 2011 by former Lord Provost John Letford and a number of business people from across the city.

The winning essays

First place — Gold Digger, by Lewis Neilson (St John’s RC High School)

The bitter breeze whistled and hissed as it crept through the derelict cracks in our wall, awakening my two brothers and me from our uneasy slumber. Every morning was the same, battling against the sheer coldness. Helpless. Left to curl up next to each other under our rough jackets as the wind jabbed away at our numb skin like a thousand needles at once. Yet, although money was certainly an issue for us, it seemed to bring us closer together as a family. We’d spend our evenings together, cosying up around our only source of light, a dim candle. Nothing could separate us; at least that’s what I thought…

I remember it perfectly… every detail, the turning point in my life.

We were congregated on the damp floor, telling our stories of the day’s harsh struggles, unable to feel much of our bodies as we nibbled on the remaining rations of bread. My mother and I spoke of our day at the local jute mill, Verdant Works. Each day was the same for us: a prolonged depressing walk to the factory, the towering chimneys towering high above the surrounding buildings as thick black smoke coughed from them, choking the air. Inside, everything seemed so vast. The machines groaned and whined from years of use; nothing ever fell still. Each day we tackled the deafening cacophony that shattered our ears and the thick dust which clogged our airways. Our coughing became relentless. I was a small, scrawny child, perfect for crawling under the working machines to recover any bits of jute which had fallen through. Sweat would pore like rivers down my forehead as I’d anxiously try to keep all my limbs attached to my body and all for a ‘generous’ few shillings a week.

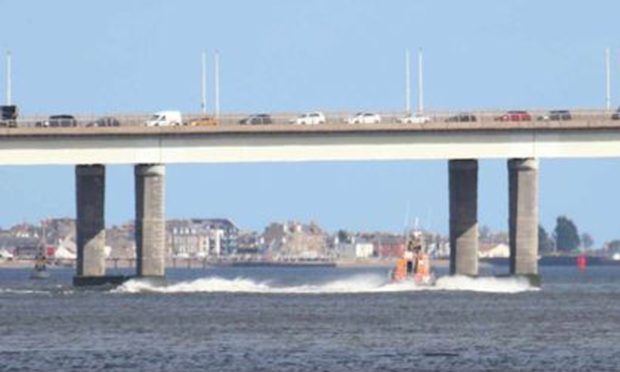

My father and two brothers didn’t have it any easier. They slaved away at the grimy coalmines over the Tay in Fife. They would work ridiculous hours in ridiculous conditions under ridiculous circumstances, all for a very ridiculous pay. Nevertheless, my father would never complain. He was a caring, considerate and commendable man always putting others first no matter what. His smile was infectious. He was our hero, a role model whom we were so very proud of, bringing light to our faces on the darkest of days and his inviting, gentle voice always warmed up the room in the coldest of hours.

He deserved so much more than this.

He told us about the claustrophobic tunnels he’d be trapped in for eight hours at a time and we listened in awe. He’d emerge from the hell hole unrecognisable, covered from top to toe in thick black soot and although seeing him stumble through the door from work brought me relief, I could never contain a chuckle.

Just when we all seemed to be dozing off and the light was slowly dying as the candle flickered vulnerably from the passing breeze, I could tell my father had news. His face was beaming and masked with excitement when he finally told us, “Th’day wis different, ah fun something doon th’ coal mines, tis worth a lot ‘n’ wull dae this fowk a hail load o’ guid.”

Our eyes widened and we all eagerly leaned forward in anticipation as good news was certainly not a common occurrence in our household. He reached for his ripped jacket and revealed a handkerchief. Resting it in the palm of his hand, he delicately unfolded it, corner by corner revealing the contents inside. I couldn’t make out what I was faced with, but my brother broke the silence, stuttering as he spoke, “Na wey is that whit ah thinks it is?”

“Tis gold, real gold, we’re aff tae be th’ richest fowk in Dundee,” my father replied frantically. We all slept like babies that night knowing it could quite possibly be the last night in this derelict, dehumanising space.

We woke like we always did, although the bitter breeze seemed to be gentler on us this morning and the wind’s needles seemed to be nonexistent. The three of us bolted into the room where mother and father had slept, expecting to join an enthusiastic conversation of what we planned to do with our newly found fortune. We were stopped in our tracks. Instead, we were faced with mother helplessly bawling her eyes out as she held a letter in her withered, shaking hands. The letter read:

“I’m sorry bit i’ve gaen, gaen wi’ th’ fortuin in search fur a freish oncom, a freish life… tis whit ah wantit”. All of a sudden, the needles were back, worse than ever. My heart sunk. Crushed, I faced reality. Bitter betrayal. My beloved father had broken us; left us stranded and hung us out to dry.

I learned a very important lesson that day, “All that glitters is not gold…..”

Second place — Cardboard Tables, by Emily Mary Crawford (Grove Academy)

Joshua lay wide-awake with his baby brother beside him. His stomach was rumbling like thunder. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d eaten a hot meal. He lay staring at the bare, depressing room that surrounded them with its single stained-mattress, an upside down cardboard box they used as a table, and a bin bag overflowing with rusty pots and torn clothing. The wallpaper was peeling off, mouldy spots dotted the ceiling, and the carpet was too revolting for bare feet.

Joshua turned onto his side. When his foot exited the cocoon of warmth beneath the patched-up blanket, it made contact with the unrelenting cold. His foot jerked sideways. For a minute he panicked and spun around to check behind him. Thankfully George was still in a deep sleep. He let out a sigh of relief. His mother hadn’t paid the gas bills yet. He hadn’t seen her in days. This was unfortunately a common occurrence.

Suddenly, the noise of the front door lock caused Joshua to bolt upright. George was still sleeping soundly. He could sleep through Armageddon, he thought to himself. He turned his attention to the bedroom door creaking open, only to be greeted by the sight of his mother carrying a white polybag. The strong scent of fish and chips wafted around the room. Does she have a chipper? His stomach roared at the thought.

‘Joshua,’ his mother whispered cheerily, ‘Wake George. I’ve got food.’ This was odd. They couldn’t afford takeaways. Joshua was about to ask her how, when the growling of his stomach interrupted him. It would be better to eat first, then ask questions later.

The three of them sat crouched over the cardboard box with the polystyrene container ceremoniously placed in the centre. Joshua was salivating at the sensational smell of malt vinegar fish and chips.

‘Mum, how’d you ge-’

‘Joshua,’ his mother interrupted in a threatening tone. He stopped talking, not asking her again. Despite the awkward atmosphere, and eating in silence, the taste was breath taking.

The secrecy of this new supply of money continued for weeks. In that time, they were given new clothes, regular meals, new furniture and a television even appeared! But the question still lingered. Where was the money coming from?

One night after dinner, George had been sent to bed early, his mother wanted to speak with him. ‘We’re moving to the ferry.’

‘What, how?!’

‘Shh, you’ll wake George.’

‘Are you borrowing money again?!” Joshua asked, indignantly.

“Joshua!” his mother gasped. She was embarrassed, she hated it when he mentioned loans. But he wanted answers.

The arguing continued for several more minutes until she blurted, ‘Fine!’ she snapped, ‘It’s from your father.’

Joshua paused. His mother never talked their father who hadn’t visited them in years. They had almost forgotten about him. His mother noticed his hesitation, and her scowl softened, ‘Your father passed away a couple of weeks ago. He left his money to us, along with a small company he owned. But there’s one condition: that you two must go to boarding school.’

It wasn’t what he’d expected. The inheritance was one thing but he had to go to a boarding school. Eventually, George would have to go too. Their mother would be alone. He was at a loss of words. He nodded and went to bed, struggling to absorb all this information.

Joshua lay wide-awake staring at the now-cosy room that surrounded him. The cardboard box was gone, replaced with a birchwood table. Cupboards filled with clothes and toys lined the walls, and instead of one shared mattress, bunk beds took its place. He couldn’t picture going to boarding school. He couldn’t picture being separated from his mother or George.

But eventually, he would have to go. How could he refuse this condition? If he didn’t follow the will word for word, they would lose everything. If he stayed, the will would be null and void. He would never allow that to happen. He would go. With his decision made, he surrendered to a restless sleep.

Three months passed and Joshua was about to board a flight for boarding school in London. Nervously, he approached security. His knees turned to mush, and his hands were clammy. He felt extremely anxious. He wouldn’t fit in; he accepted that. What worried him was George. When he looked back at George, he looked so small and appeared as if he was about to burst into tears. Joshua felt a jab at his chest. He wanted to run back and tell him that he’d stay there with him. But instead, he waved goodbye to them both and proceeded through security.

Third place — A Catastrophic Fortune, by Lucy Johnston (St Paul’s Academy)

The wind was bitter and crisp. Each surface, more glacial than the last. The rain, battering against the roof, producing a sound that can only be described as the rolling, rumble of waves against the sea shore. The air forced it’s way through the cracks in the windows, through the slit in the base of the door, surrounding each room with a blanket of wintery frost. The wooden floorboards were damp from a leak in the ceiling and the stench had made it’s way into every single piece of furniture they owned. The accommodation had a sombre feel; the presence of nothingness would even unease the dangerous beings of the dark. A snarl radiated from a dingy corner, reverberating throughout the house. A mess of a man emerged from a heap of torn rags (of which he called ‘a bed’) on the splintering boards.

“Shut up Bert, you old mutt!”

The mongrel stared at it’s owner.

“It’s only rain!”

A feeble figure of a twenty-four-year-old looked at the beast. His hair, dishevelled and dense, blanketed his head and his once-fitting clothes now baggier than the eyes of an insomniac. His bones as visible as a solitary lantern in a dark forest. He shuffled towards a cracked window pane, behind his so-called bed, and peered out to the almost deserted street, to see the horse and cart of the rag and bone man, then he noticed his brother, Samuel, delivering newspapers. Samuel was a young, healthy teen, small for his age, but with a heart too big for his chest. He had always been the tidiest of his brothers, caring about his looks more than his physical health. The spectator shakily lifted a bottle of cheap gin to his pale, cracked lips. The door swung open.

“Edward! Are you drinking again!?” Samuel bellowed.

“Why would it matter to you?” Edward grunted.

Samuel looked down in disappointment.

“Is there any money for dinner?”

“No, we used it to sole your shoes, remember?” Edward replied.

“But we had some left…”

“And I was tired of being sober.”

Samuel stormed out in disbelief, slamming the door so forcefully that the entire house shook.

Edward sighed, “More for me, I guess.”

He took another swig of the alcoholic beverage.

Edward had always admired his brother, Samuel, so hardworking, so determined, so caring but sometimes his temper would get the best of him. Victor, on the other hand, had always been led by his aspirations: singing in the local church choir. Victor would regularly participate in singing competitions. In fact, he was doing one right now, in which the grand prize was a bursary placement in London Royal National Theatre.

Edward gulped down another mouthful of the burning liquid.

After their father, William, died of the drink, their mother, Margaret, took her own life, unable to bear the agonising grief. Although Samuel and Victor were coping as best as they could, Edward was suffering from low mood and his nerves. He too had now taken to the drink.

Edward looked at the calendar, ’28 December 1879.’ He had almost forgotten that Christmas had been three days ago, not that he would have celebrated anyway. He took another shot of gin.

Edward remembered the last time he felt any sort of happiness. He took a train across the Tay Bridge to Fife, with his brothers, to have a nice family day out. It was a lovely summer’s afternoon, if he tried hard enough he could almost feel that gentle sun on his face. They visited Balmerino and the Abbey ruins. But, since then, everything had gone downhill. He had just stopped caring about life and started to wish death upon himself.

Edward looked at the almost empty bottle of gin. He laughed, as he had even impressed himself by the amount of alcohol he had consumed. Edward crawled over to his ‘bed’, covering himself in the rags, he heard a familiar monotone voice.

“You’ve disappointed me, Edward. You’ve disappointed your entire family. Just given up, already!”

“Dad! You’re not real!” Edward screamed, as he realised he was hallucinating.

Edward opened one last bottle of the intoxicating solvent, and downed it entirely. He stared at the clock, which read ‘7:15pm.’ He closed his eyes, as his life slowly began to ebb away.

******

Samuel burst through the door, almost snapping the hinges “THE TAY BRIDGE COLLA…”

Samuel stared at Edward’s inanimate body.

“Edward…? Edward…EDWARD!”

Samuel was standing over Edward’s body, deprived of all life. His skin was blue and colder than ice. His eyes, no longer a window to the soul, but rather a window to nothingness. This was the only time that Edward had seemed so…’alive.’ Bert lay still in the corner, unaware of all the events that had just unfolded.

Victor barged through the doorway.

“I’VE WON!”