Michael Alexander speaks to author Vicki Masters about her inspirations for an historic novel set against the backdrop of the infamous Siege of St Andrews Castle in 1546/47.

When German cleric Martin Luther began protesting against the practices of the Catholic Church which led on to the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation in Europe during the early 16th century, it led Scottish clerics such as John Knox to embrace this new theology and revolt against the Catholic Church in Scotland.

By the 1540s, Cardinal Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews, was the head of the Catholic Church in Scotland and in a bid to stamp out growing revolts, he condemned many to be burnt at the stake after they were tried for heresy.

When Beaton had Protestant preacher George Wishart burned in front of St Andrews Castle on March 1, 1546, he hoped it would bolster his authority and quell growing religious tensions.

However, in May 1546, a group of Protestant conspirators gained entry to Beaton’s residence at St Andrews Castle, disguised as stonemasons, and assassinated him.

After being repeatedly stabbed and mutilated, Beaton’s body was hung out on display at one of the castle windows as the conspirators occupied the castle.

For 14 months the conspirators were besieged by the Governor of Scotland, Regent Arran.

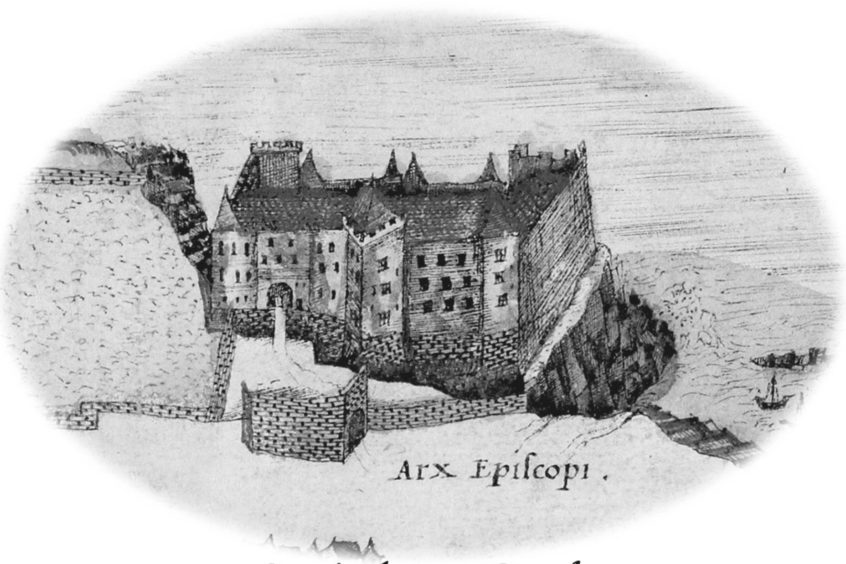

It resulted in the creation of one of the castle’s most remarkable features – the mine (dug by Regent Arran’s troops) and countermine (dug by the Protestant rebels).

These underground passages of medieval siege warfare are unique and a source of fascination for visitors to the castle to this day.

However, over 18 months the Scottish besieging forces made little impact, and the castle finally surrendered to a French naval force after artillery bombardment.

The Protestant garrison, including the preacher John Knox were taken to France and used as galley slaves.

It’s a remarkable story that has captured the imagination of thousands of visitors over the years – particularly those brave enough to go down the mine/counter mine and to peer into the infamous bottle dungeon where Beaton’s body was stored in salt.

Has Scottish history been given enough coverage in schools?

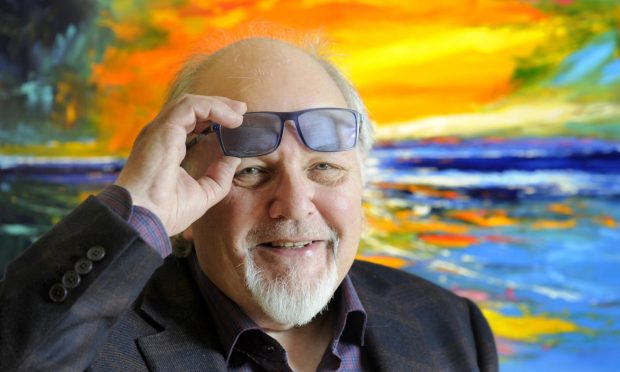

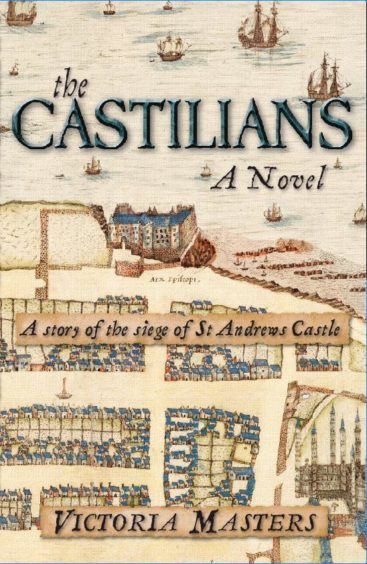

Yet when former Fife woman Vicki Masters, who went to school in St Andrews, decided to write a historic novel – The Castilians: A story of the siege of St Andrews Castle – set against the backdrop of the siege, she realised how little meaningful Scottish or even St Andrews history she had been taught at school.

“We were told a little bit in primary school,” says Vicki, 66, who attended the old Madras College Primary (West Infant) and Madras College.

“We were told about the terrible burning of George Wishart and before that Patrick Hamilton.

“It was done by this ‘evil’ man Cardinal Beaton and then we were told – in revenge quite rightly – these people had stormed the castle and murdered the cardinal.

“But it was a very Protestant-centric story, and there was no mention of Henry VIII’s huge influence and how these men were pensioners to Henry VIII – he was paying them, his ‘assured Scots’ as he called them.”

Growing up on a farm at Nydie, near Strathkinness, Vicki remembers being fascinated by the history of the area.

There were old quarry workings and tunnels on the farm where stone had been removed by monks to improve Balmerino Abbey.

However, she was 12-years-old before she visited St Andrews castle for the first time thanks to a visit organised by her history teacher Miss Grubb.

She remembers getting excited about the mine and countermine and the bottle dungeon where the cardinal’s body was kept pickled in salt for the whole 14 months of the siege.

However, even when she went on to study history for two years at Stirling University, she remembers there being “very little exposure” to Scottish history.

“It was almost like we weren’t told our stories,” she says.

“Mary Queen of Scots and that was about it. Even at Stirling University there was some interesting modern history.

“But there was hardly any Scottish history. It was as if it wasn’t a big thing to learn about Scotland. It felt overlooked.”

What is the context of the book?

Graduating in sociology, Vicki had thought about becoming a social worker before marriage and having three children changed her plans.

Living in Markinch, Pitlessie and KIngskettle over the years, she worked latterly in organisational development and executive coaching.

When her family grew up, she took a career break and worked in Namibia for 18 months doing Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) in the mid-2000s.

She also dabbled with writing and while she’s worked on a few novels over the years, completion of The Castilians is the first she’s completed and released.

“It follows the whole period of the siege,” she explains.

“It starts with the burning of George Wishart. It’s grim. It’s factual.

“I was very interested in what it would be like for the people of St Andrews during this time.

“What it would be like to be stuck in the siege. You’ve got these guys in the castle, you’ve got the town filling and emptying with soldiers.

“Then you’ve got the people in the castle – it took a while for the soldiers to arrive so they are coming and going: taking things like lords of the countryside and they are attacking people and women.

“And the soldiers come and the town is absolutely hoaching with soldiers and you get pestilence and so people are trying to live through that.”

Vicki explained how she tells the story through the eyes of a brother and sister.

The sister is outside and the brother, who believes in the need for reform, has gone in to fight with The Castilians.

He’s fighting with them because he really believes the church needs to reform.

Yet at the same time he’s not entirely comfortable with some of the things the rebels are doing.

His sister is calling for him to come out – warning that if he doesn’t the family might be punished and lose everything. But he insists he must stay with his men.

At the same time, the sister is getting pushed to make a suitable marriage that might protect the family, and she doesn’t want to do that.

“It’s about this challenge of loyalties,” says Vicki.

“It’s about what do we choose – ourselves or our family? Do we follow our heart? Do we do what’s right? Do we look after our family? Do we do what’s most important? They are really beset by these choices.”

To help with research, Vicki used material at St Andrews University Library and the National Library of Scotland. She was mainly looking at secondary sources.

Biographies of John Knox and Cardinal Beaton were helpful, as was a course at St Andrews University run by Dr Bess Rhodes who looked at the riches and rewards of the church and how it was impacted on by the Reformation.

Perspective

She also found herself crawling on the rocks below the castle at low tide to get the perspective of how the castle looked from the sea.

Yet even now, Vicki remains surprised how little has been written about much of the detail.

“There’s bits and pieces,” she says.

“Take the siege tunnel. The reason we know that’s when it was built is it’s mentioned by the French ambassador to the English court who writes about them digging a siege tunnel in October 1546. That’s about the only reference to it. Knox doesn’t mention it.

“But there was a real business in dealing with sieges.

“The Italians were experts at it. The guy that finally gets them out is an Italian who’s working for King Henry of France.

“The main way they got them out was they hauled canon on the top of St Salvator’s and the cathedral towers and fired on them from there. That’s what got them out in the end.

“The Italian siege engineer Strozzi – he criticised the Castilians for not knocking down those towers because if they had it would have made his life much more difficult because they wouldn’t be there to fire canons from.

“Imagine how that would have changed the skyline of St Andrews if St Salvator’s wasn’t there and St Rule’s Tower ? It’s really interesting.”

Vicki says she always had a “sixth sense” she was going to write this book.

When she heard the name they called themselves was The Castilians, she remembers thinking “that’s great, that’s perfect”.

She’s not finished yet though.

Vicki is already planning a sequel that continues the story of the brother and sister and where they end up and what happens next after the siege.

She’s also got another book half-finished which is based on her mother in law’s experiences in the Second World War aged 16 going overseas with ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association).

*The Castilians: A story of the siege of St Andrews Castle by VEH Masters is available now. The publisher is giving away 10 signed copies through The Courier. To have a chance of winning a copy, send your details to features@thecourier.co.uk by 9am on Wednesday January 13 to enter the draw.