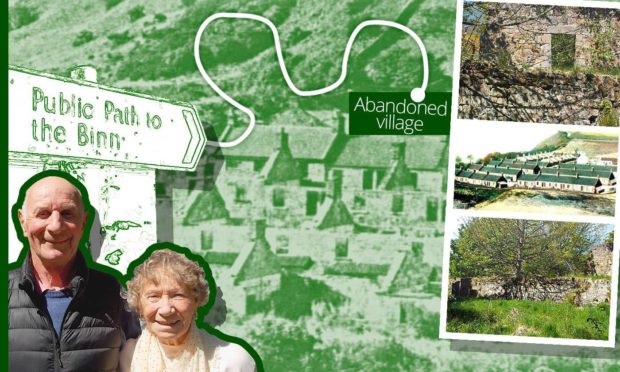

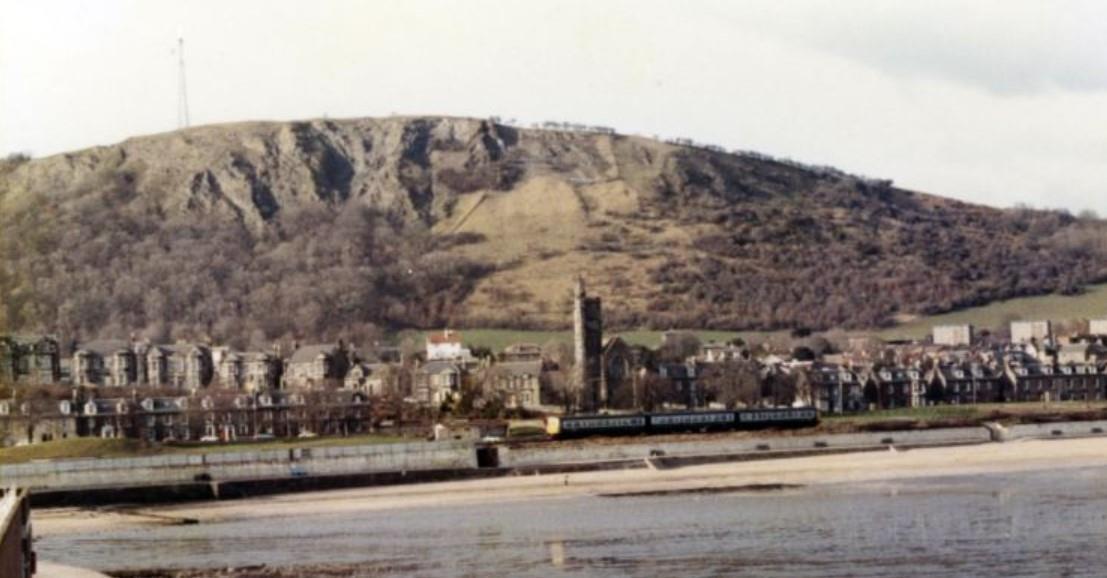

Nestled among lush woodland on a steep hill above Burntisland is Binnend – a former Fife village that has been left abandoned for the past 67 years.

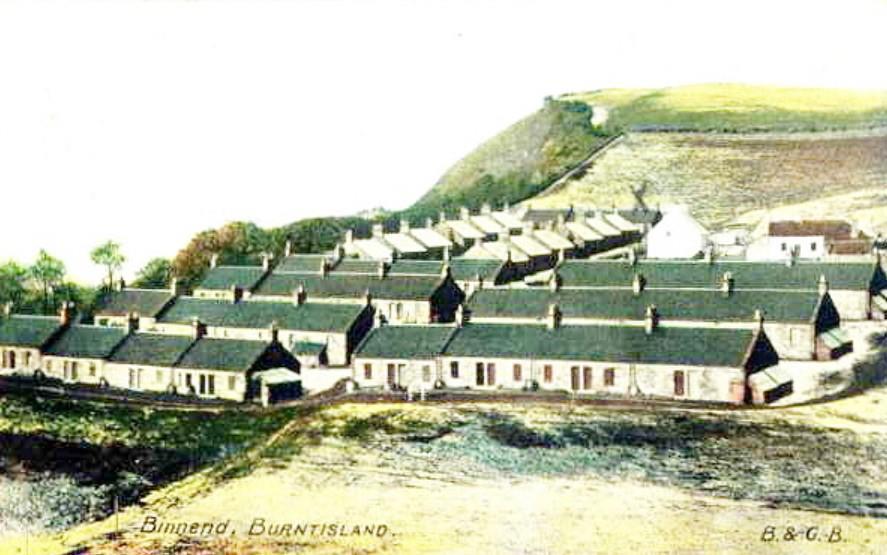

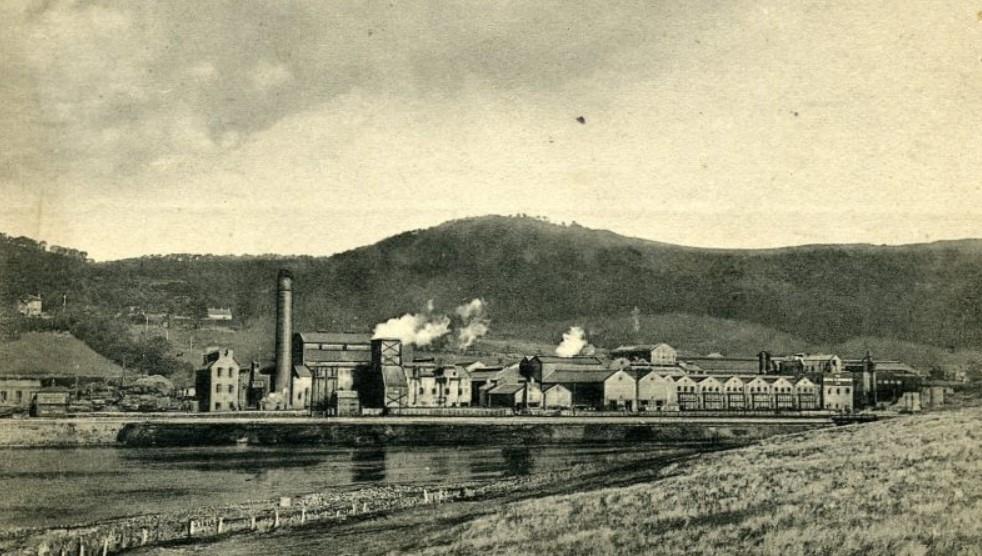

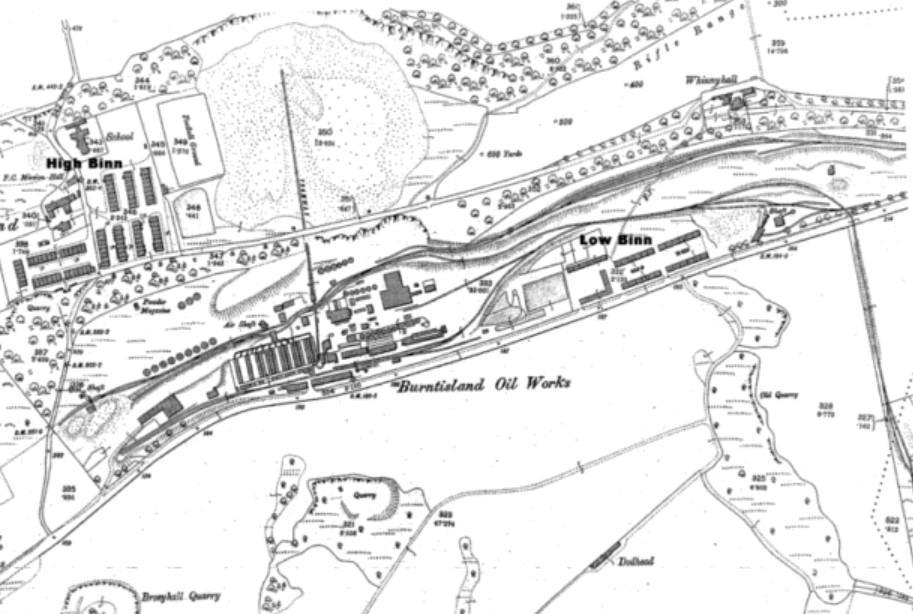

Known also as The Binn, or High Binn, the village was established at the old Binnend Farm to serve Burntisland Oil Works, which were in operation between 1878 and 1894.

There was also a settlement at the Low Binn, which was built close to the main road – now the B923, east of the oil works.

At its peak the oil works, located opposite Burntisland Golf Course, employed almost 1,000 people.

According to the Burntisland Heritage Trust, Census returns show that the High Binn had a population of 564 in 1891, crammed into 95, mainly two-roomed, houses. The population of the Low Binn was 192, in 33 houses.

In 1889, the High Binn acquired a Free Church Mission Hall, which seems to have served all denominations; and in 1891 it got its own school.

At that time, there were around 170 children of school age. The village had a football pitch, nestling at the foot of a shale bing, and home to the Binnend Rangers.

There were two small shops in the village, but the inhabitants went to Burntisland for most of their messages.

When the oil works employees were paid off in 1893, Binnend village remained a going concern, although its permanent population began to decline.

There was a brief revival during World War One, when troops and dockyard workers occupied houses and the school.

And when the British Aluminium Company (latterly Alcan Chemicals) and the shipyard opened in Burntisland around the end of that war, the village provided low-cost homes for a number of the incoming workers.

Overall, 30% of the heads of household were Irish, with most of the rest born in Fife or the Lothian shale mining areas.

But the absence of basic facilities led to the formal closure of the village about 1931, although some residents insisted on staying on, despite the lack of piped water, gas, electricity and sanitation.

The only road was a rough farm track allowing slurry from the aluminium works to be dumped next to The Binn.

By 1952, only two couples, the Hoods and the McLarens, remained. Early in 1954, the last inhabitant, 74 year old George Hood of number 133 High Binn, departed.

The village was left to the mercy of the Territorial Army, Alcan Chemicals, the weather and the vegetation. Today very little remains of what was once a thriving settlement.

Video footage below shows two former residents, Bill Black and his sister Margaret Frew, returning to the site of their childhood home.

‘It’s a unique place’

The presence of water supply in their home meant Bill Black and Margaret Frew were among the lucky ones living in The Binn.

Bill, now 77, and Margaret, now 81, respectively spent their first seven and 11 years at the village’s Princes Street after their parents, William and Kate Ann Black, moved in from the Edinburgh area.

William, who worked at the aluminium works, installed a water supply to ensure the family did not need to use standpipes outside the houses.

He also had a separate “hidden” garden that grew fresh vegetables and flowers. There were even chickens there.

But there was still no internal toilet or mains electric at the house and lighting came courtesy of paraffin lamps.

Bill, who was born in 1943, says: “There were quite a few other kids up there and we used to run around and play a game called ‘kick the can’. It was a very simple game and we had a very simple life up there.”

Children living in Binnend went to the old Burntisland School in Ferguson Place. This meant a steep journey down the hill in the mornings and a challenging trek back up at the end of the day.

Bill recalls the infamous winter of 1947 when snow gathered “20-foot high” and makeshift sledges were created from the red shale that was dumped from the aluminium works. Occasionally he would get a lift up the hill in one the trucks.

“I thought it was wonderful,” he says. “We were in the fresh air and surrounded by trees. It was a nice place to be brought up.”

In 1950, the family moved to Colinswell Road in Burntisland.

“The aluminium company would have said to my father that the village was closing down so offered him housing in the town,” William says. “It’s progress, I guess.

“I recall that last day being in the back of a Frontier van and looking back at the village as we went down the road. It was really sad to leave.”

Bill stayed in Burntisland as he forged a career at Aggreko in Dumbarton. In 1989 he relocated to Melbourne in Australia to help the company expand.

Three years ago he returned to Fife and now lives in Kinghorn.

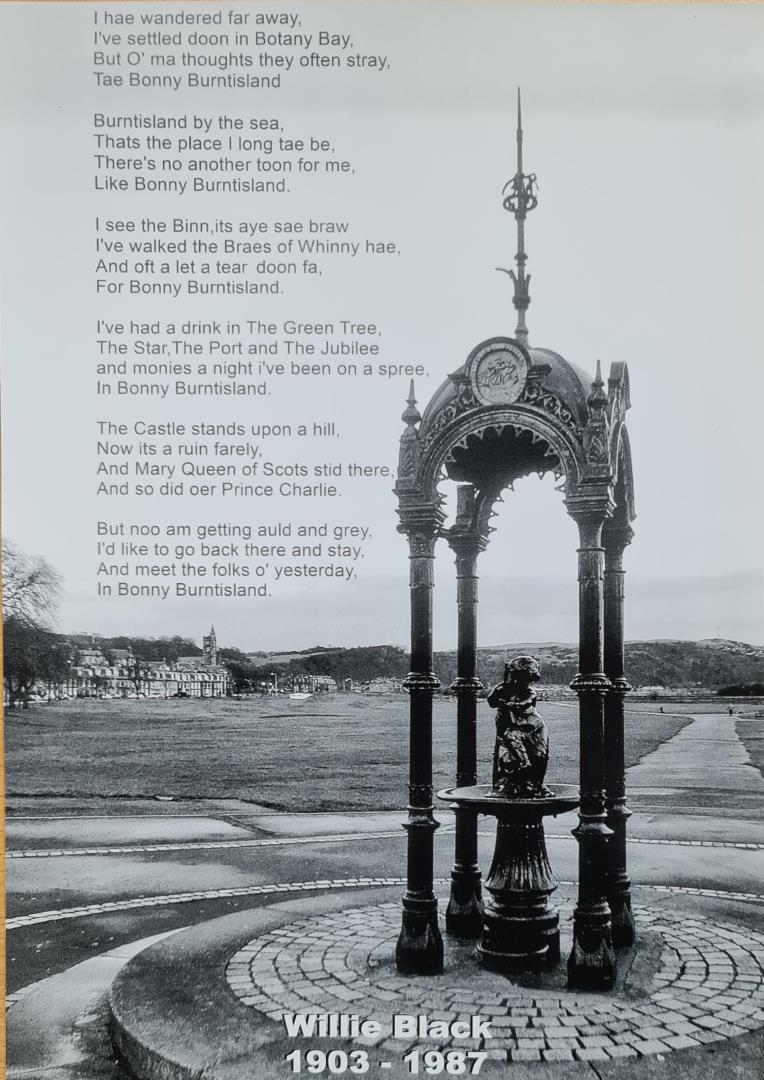

“I go up to The Binn all the time for my walks and to look at the wildlife,” he says. “When I play golf at Burntisland twice a week it is also in front of me, which is comforting.

“It is now buried, with a fence around it. You would not know there had been the village there.

“I’m proud to say I come from Binn village. When I tell people I lived there they often look surprised and shocked. It’s a unique place.”

‘We had to walk around with a torch when it was dark’

While the Black family lived in The Binn the permanent population was on the decline but many of the houses found a new role as holiday homes.

Basic they might have been, but visitors from the cities loved the fresh air and

freedom. The large number of Binn village postcards from that time are now invaluable as a permanent historical record of a lost village.

“Because my father came from Dalkeith and mum from Edinburgh all the relatives came here for holidays. They thought it was lovely,” says Margaret Frew.

“My mum was one of seven sisters so we had lots of visitors. On a clear day my dad could look through his telescope and tell the time on the clock of the Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh.

“There was no street lighting on The Binn so we had to walk around with a torch when it was dark.”

When Margaret visited Binnend in May 2021 – around 40 years since she was last there – she saw the village had been sealed off and become a no-entry zone.

“It was a wee bit disappointing not to be able to see exactly where our home was,” she says. “But it was lovely to come back.”

Dad ‘could see’ German pilot

German air forces targeted the aluminium works during World War Two.

On one occasion, sometime between 1943 and 1945, a plane was said to have missed the works and dropped bombs on a field near Cowdenbeath Road.

“My dad told me that he was walking me in a pram when a plane came zooming over,” says Bill. “He says he could actually see the pilot just before he dropped the bombs.”

The craters on the field were said to be a local landmark for many years.

‘You certainly had to be tough to live up there’

“It was a great place for children but not so good for adults” is how Peter MacGillivray sums up living in Binnend.

Peter, now 86, lived in the village with his father Peter and mother Betty for the first 15 years of his life.

In this time he was also joined there by three younger sisters.

“It was primitive to say the least,” says Peter. “The outside toilet was a dry toilet that had no water in it.

“It was like a bucket that you had to empty in a midden and then disinfect it.

“There was one bedroom and living room, which included a Primus stove to cook food.

“It must have been terrible for women to cook on it and to wash anything you had to go to a separate building.

“The food had to be brought up from Burntisland, which meant walking up and down a hill for a mile. Rationing was also an issue.

“There was only one phone in the village, which was in Mr and Mrs McLaren’s home so you had to go to them if you needed to call a doctor.

“You certainly had to be tough to live up there – especially in the winter when it was wild.

“I remember one winter it was so cold that the water pumps froze so you had to go to a horse trough to get some water to clean with. I remember doing this and being chased by sheep!”

Peter’s dad was a joiner for the Ministry of Defence at Donibristle in Dalgety Bay.

“My parents would have lived at The Binn due to a lack of housing,” says Peter.

“Most of the people living there would have been waiting to be rehoused in Burntisland.

“The houses were privately owned and they would have been paying rent with the rates waived because of poor facilities.

“The kids didn’t mind it at all. We had open countryside and you could roam anywhere without parents worrying about anything happening to you.

“We could go up and down the hill no problem but for older people it was a death trap.”

The family moved to Aberdour in 1950.

“We were quite happy to get away to get proper facilities,” says Peter. “We moved to a house that had a lot more room for the family.”

Peter, who has been writing a book about his experiences at The Binn, worked at Rosyth Dockyard and then on nuclear submarines, living for a time in Singapore.

He now lives in Dunfermline.

‘We had a bunk bed in the curtain area’

David Jack was five when he moved from a flat above the Green Tree Tavern in Burntisland High Street to 13 Belvedere Terrace in the High Binn.

It was 1944 and his father William Taylor Jack orchestrated the move after getting a job for the British Aluminium Company. Also joining them in the house was David’s mother Elizabeth and younger brother Robert.

“For children it was fine but for adults the lack of facilities must have been horrific,” says David, now 81.

“When we were living above a pub we had internal water, sewage and electricity but there was none of that at The Binn.

“In the living room we had a bunk bed in the curtain area.

“As kids we would go out on Saturday morning as a group and would not be back until the evening.

“The village had shale mines and we would find an entrance to it and wonder in for two to three metres before we got scared and came back.

“Sometimes we would go to Orrock Farm and we also might visit a wee loch called Silverbarton.

“We used to wander to these places and our parents didn’t seem to worry about it.”

In 1950, when David was 12, the family left for a home in Lothian Road, Burntisland.

“When we left a lot of the village was empty and derelict. Only a few homes were habitable.

“It was sad to leave but as a family we had a lot of connections to Burntisland. My grandad, for example, lived in Seaforth Place.”

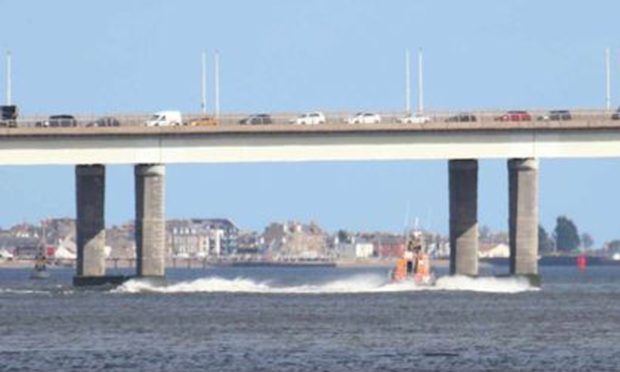

David went on to work for the National Coal Board as a mine surveyor. He later moved into civil engineering and was involved in the construction of Forth Road Bridge.

He worked for Fife Water Board and then took on a similar role in Glasgow, where he has lived since 1985.

Some slept between the ceiling and roof

Some of the houses in Binnend were so overcrowded that the beds were used on a shift system, 24 hours a day.

In some cases people slept in the space between the ceiling and the roof.

It was not that bad for John Forrest, now 87, but he was one of five people having to squeeze into two rooms.

He shared the house with his father, mum Sarah, brother Walter and another girl, Freda.

“All we had were two rooms for five people,” says John, who lived in the village for the first seven years of his life, leaving in 1940.

“The first room was used as a living room, diving room and bedroom. The others had beds in it.”

His family had to get water from a well and bathe in a communal washhouse.

John, who went on to work as a miner in Frances Colliery in Dysart, adds: “All of the houses are now gone, which makes me feel sad.”