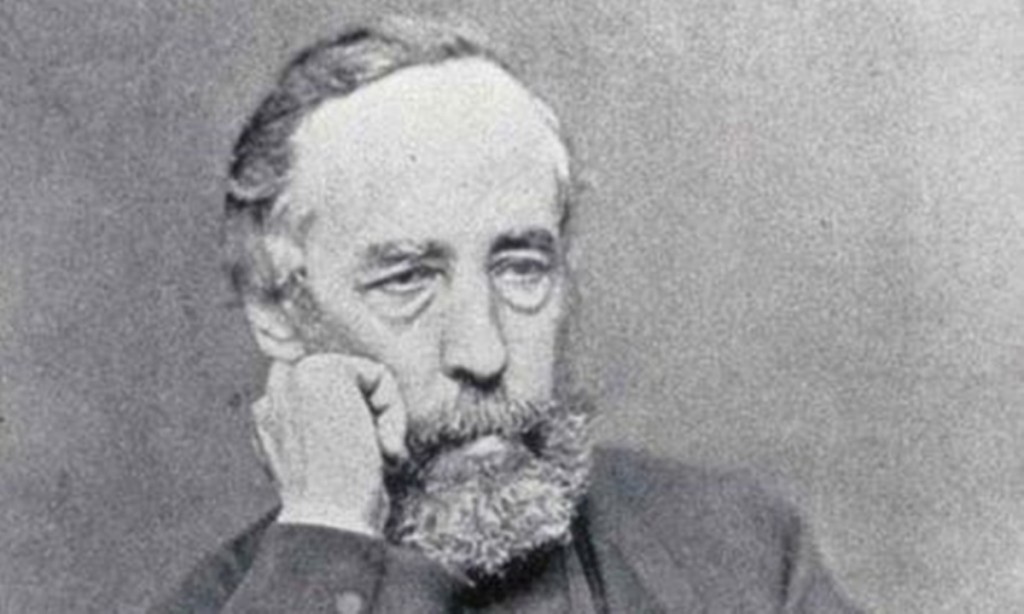

Two hundred years ago, climate science pioneer James Croll was born into relative poverty in Perthshire, yet he is largely unknown outside academia. Here, Michael Alexander learns more from Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society chief executive Mike Robinson ahead of an online talk about his life.

He is the Perthshire-born scientist who made his living as a janitor by day and pioneered our modern-day understanding of climate science and glacial history by night.

Yet in the year that the rescheduled UN Climate COP26 in Glasgow will focus the world’s attention on Scotland, the remarkable achievements of James Croll have been largely forgotten.

Visitors to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) headquarters in Perth may be aware of the Croll Garden which was named in his honour some years ago.

But on this, the 200th anniversary of his birth and ahead of an online talk on January 6 about his life, RSGS chief executive Mike Robinson is hoping that the forgotten “genius”, who was plagued by ill health and left school barely literate, will help inspire a whole new generation.

What did James Croll discover?

“James Croll was a really clever thinker,” says Mike.

“He predicted the thickness of the Antarctic ice sheet before anyone had ever been there.

“He predicted the rate of the degradation of mountains in America because of the records of saltation at the mouth of the Mississippi.

“And all of these things that he did to calculate the age of the Earth, the age of the sun and understand the principle of glacial epochs is really pretty remarkable.

“He was ahead of his time in many ways because it wasn’t until actually 1976 that we could even prove some of his theories.

“But his theories are all the more remarkable in light of his personal story.

“How did a man of such modest birth, who was plagued throughout his life with ill health, and who left school after only three years, barely able to read and write, become one of the leading scientific thinkers of his day?”

About James Croll

Born on January 2 1821 to David Croll, a stonemason and crofter, and Janet Ellis, formerly of Elgin, in the hamlet of Little Whitefield, about five miles north of Perth, the family were forced to move when James was three years old after the croft was cleared by the landowner Lord Willoughby.

Some families were encouraged to relocate to Burrel Town, a mile or so east, and others were offered an area of derelict bog-land a mile or so west, in some sort of recompense for being displaced.

This latter area became the village of Wolfhill and here James’ father managed to clear between four and five acres and build their own house.

Having previously farmed an area of closer to 20 acres, as Croll’s family had for at least the previous 200 years, it was not possible to feed the family from such a small land-holding, so James’ father had to revert to his trade as a stonemason and travel regularly away from home. It therefore fell to James to farm the land.

But James was afflicted with a pain in his fontanelle which would have required him to wear a hat in class to keep his head from hurting.

This was enough to put him off attending school, so up to the age of eight he was schooled in part by his parents, occasionally by a visiting school teacher, but in main by his elder brother Alexander.

Unfortunately Alexander died at the age of 10, and James was forced to attend school himself from that point onwards.

James, whose younger brother William had died two years earlier at a few months old, attended school in Guildtown from the age of nine.

But he found the teacher to be “too tyrannical”, says Mike, and did not fare well.

Below average student

When he finally left, aged 13, to help manage the croft, by his own admission he was below the average student.

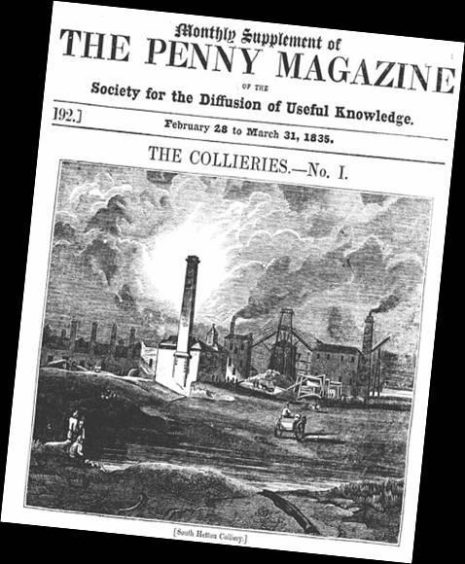

But it was around this time that he stumbled upon the monthly ‘Penny Magazine’ of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge in a shop in Perth and suddenly his intellect was unleashed.

“Croll read avidly from this moment forth,” explains Mike, “and by his late teens felt he had a pretty good grasp of most of the main disciplines in science.

“Ironically geology was one of the few subjects he struggled to find much enthusiasm for.

“At the age of 17 James had to go and get a job, and he moved the two miles to Collace, to learn to be a millwright.

“After almost six years of what were fairly poor living conditions on the road, he finally tired of the job and was relieved to move back to Wolfhill, where he took himself back to school to learn algebra.

“As a 22 year old in a class of children he was a novelty, albeit not unique in classrooms of that period, but it is again evidence of his desire to learn.”

New theories about glaciation

It was at this time that a leading Swiss scientist, Agassiz rocked the Swiss geological community by first reporting his theory of glaciation at a conference in Neuchatel.

Up until this time most scientists believed that massive rocks, which had travelled large distances from their source had been washed there in the biblical floods that Noah survived.

The idea that glaciers covered larger areas and had deposited rocks there but had now retreated was controversial and widely disputed, but it was Agassiz in 1837 who first formally presented this theory.

A deeply religious man who worked as a joiner to help build his friend, the Reverend Andrew Bonar’s new Kirk at Kinrossie (now the village hall), Croll moved to Glasgow and then Paisley where he continued to work as a joiner for three years, until 1846, when his elbow became ossified and he was forced once again to return to Wolfhill.

He began working for Bridgend coffee merchant David Irons in Perth for some months, before Irons set him up in business in Elgin with his own shop.

Whilst in Elgin he met and married Isabella MacDonald from Forres who helped him with the shop, but within three years, he became ill and unable to work and was forced to sell it and move back to Perth.

Staunch tee-totallers, he and his wife established a Temperance Hotel in the Well Meadow in Blairgowrie, but it was perhaps predictably unsuccessful and he once again had to sell up.

He then worked as an insurance salesman in Dundee, Edinburgh and then Leicester, but, as a retiring and modest man, was never comfortable in the role.

This time it was his wife who became seriously ill, and they were forced to move back to Glasgow where her sisters could help with care.

First scientific papers

Croll took some time at this stage to produce his first book, “The Philosophy of Theism”, and tried his hand as a journalist on a temperance newspaper in Glasgow.

Then finally, at the age of 38, in an age when the average life span was barely mid-40s, he finally got the lucky break he needed.

Paid just £1 a week (equivalent of £3,500 salary today), plus taxes, coal and a house, he got a job as a janitor at the Anderson College in Glasgow.

But he was the happiest in his work that he had ever been as he now had access to the extensive library.

Fairly quickly he began to develop more and more scientific papers.

In 1864 Croll waded into the glacial debate and wrote a critical paper for the Philosophical Magazine : “On the Physical Cause of the Change of Climate During Glacial Epochs”.

He proposed that there were in fact several ice ages and that they were brought about in part by changes in the orbit of the Earth round the sun; the tilt of the Earth in space, particularly in relation to the different seasons; and by the ‘wobble’ of the magnetic poles over time.

This began a period in which Croll corresponded regularly with many of the greatest scientific minds of the day including Darwin, Tyndall, Lyell, Wallace, Lord Kelvin, Joseph Hooker and Fridtjof Nansen.

In 1867 he was persuaded by Archibald Geikie to join the Geological Survey of Scotland.

In 1875 he published his most critical work, the distillation of his theory of ice ages and earth’s orbit, called “Climate & Time”.

In 1876 – the year his only surviving brother David died – he was made a fellow of the Royal Society, an Honorary Member of the New York Academy of Sciences and he was awarded an Honorary degree by St Andrews University.

However, forced to retire early aged 59, from the continuing ill health that had so plagued his life, he was forced to move into rented lodgings in North Methven Street in Perth after failing to get an enhanced government pension.

Death

He was later given a monetary ‘gift’ by the Geological Society which allowed him to see out his days in a house at 5 Pitcullen Crescent in Perth.

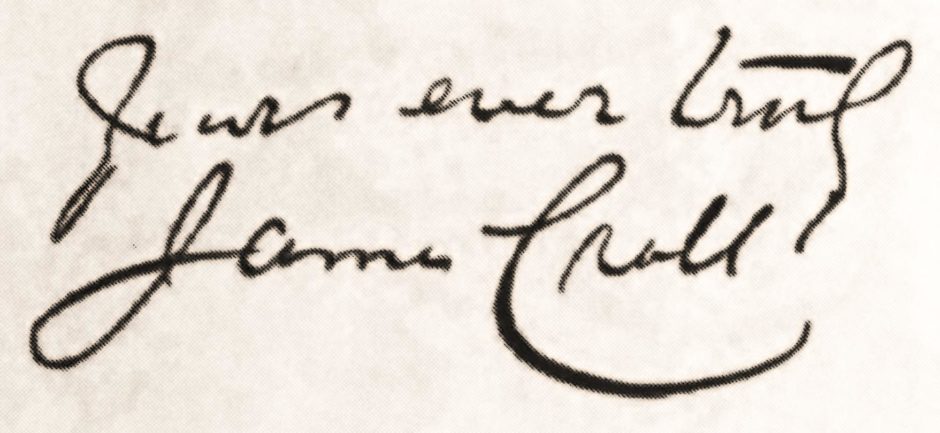

Mike adds: “James Croll died on December 15 1890 and is buried in Cargill churchyard on the banks of the Tay, close to the area in which he grew up.

“In all he produced 92 scientific papers, wrote four books and although elements of his theory were incorrect, he opened the door to an understanding of the links between the sun and the Earth’s climate, paving the way for Milutin Milankovitch (1879-1958) and others to refine and develop his thinking.”

*For more information about the online RSGS James Croll event at 7.30pm on January 6, 2021, go to https://www.rsgs.org/Event/james-crolls-bicentenary