Michael Alexander visits Seamab, a national Kinross-shire based charity which helps some of Scotland’s most vulnerable children, and which is now seeking the help of Courier readers to fund-raise for a new school.

The 10-year-old boy seemed like any other bright, smiley child as he arrived at his new home amid the beautiful Kinross-shire countryside.

The youngster, moving to the area from the Highlands, appeared full of enthusiasm as he was introduced to his teachers and other staff, who showed him the classrooms, the outdoor education play area and the bungalow where he would be staying.

But suddenly the convivial mood changed. “Are their rules here?” the boy asked his social worker as he took in his new surroundings.

“Yes we’ve got rules here,” the staff replied, explaining the timetable for education, activities and bedtime.

“Well you can keep your rules because I’m no’ ‘effing’ following them!” the boy replied.

Brian Fearon, 67, the chairman of the board of trustees at the charity Seamab, smiles when he tells this true story, quoting the boy’s more colourful language in full.

The former director of social work with East Dunbartonshire Council doesn’t condone this type of behaviour at the residential primary school for vulnerable children.

But he understands the reasons for it and like the rest of the 80-strong Seamab team, is committed to offering a therapeutic and nurturing environment for children with severe social, emotional and behaviour difficulties.

“To have a 10-year-old staking out his territory and pushing the boundaries like that is just typical of the kids we get here,” explains Brian in an interview at the Seamab school outside Rumbling Bridge.

“The thing about our children is that they do not understand the social norms, the social graces.

“When they arrive here they have been battering away at the world and trying to make some sense of it. What we have to help them get past is that first way of looking at the world with suspicion and distrust, to start to relax a little bit and to start to trust the adults.”

Roots

Seamab’s roots date back to the 1930s when a Rumbling Bridge couple decided to set up a school for local ‘poor children’. For the past 27 years, the charity has specialised in looking after some of the country’s most vulnerable youngsters with complex needs and it can now accommodate 15 residential and one-day placement.

Children aged five to 13, referred by local authorities from all over Scotland are looked after by a range of staff including carers, teachers, therapists and social workers.

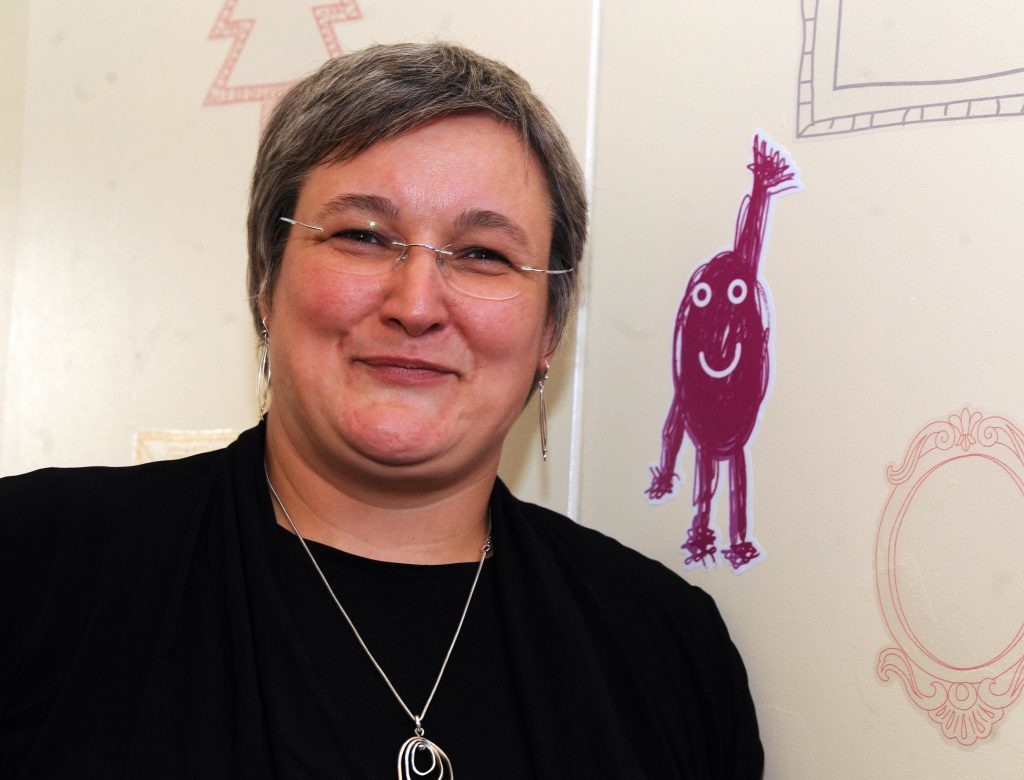

Seamab chief executive Joanna McCreadie, 46, a former social worker, says that “typical” residents at Seamab are little boys who have most likely experienced severe trauma, loss, violence and neglect in their young lives.

Often its children on the child protection register who have been identified as being at risk from a young age. Professional support, fostering and other residential placements will have broken down because the behavioural challenges have been too intense for their previous carers.

Because children have missed out on emotional support at a young age, their behaviour can pendulum erratically and they often lash out violently or chaotically.

‘Final opportunity’

But rather than offering a place of “last resort”, Seamab prefer to see themselves as a place of “final opportunity” with the average child staying for between two and four years.

“The challenges the children bring are generally they are very angry and very scared often at the same time,” says Joanna.

“They are kids who have learned from a young age they can’t rely on adults and are so sensitive to anything they see as criticism or disapproval.

“We help the children begin to believe in themselves and trust in others.

“We reassure them that whatever happens we are going to see this through with them. They won’t be thrown out of the door. We offer complete unconditional acceptance.”

Seamab is only as good as the staff team, says Joanna, with great patience and commitment required every day in the face of aggression, verbal and physical attacks by the children.

Seamab’s approach is based on an understanding of child development and is committed to a child-centred, attachment approach which comprises a mix of preventative and reactive work. The emotions of the child are explored, helping them to become more balanced over time.

Ultimate aim

The ultimate aim for every child is to help them heal, grow, learn and meet their potential.

Some will be supported back to their families, into foster environment or into their next placement.

But the biggest single challenge facing Seamab is funding. It costs local authorities £220,000 per child per year to send a child to Seamab, and with budget cuts across the country, the number of referrals has reduced over the past three years.

By comparison it costs the taxpayer an average of £300,000 per year to send a child to a secure unit.

With 25% of Scotland’s prison population made up by adults who grew up in care, the long term benefits of finding looked after youngsters a positive road in life are clear.

In the past, Seamab had difficulty connecting emotionally with potential donors and the local community.

For privacy reasons they can’t show the children’s faces in promotional material or tell their specific stories which in turn made it difficult to engage with the outside world – and fund raise.

It led Seamab to create a new brand identity and, with a little help from the children, it developed Sea Changers – a set of characters who give Seamab an endearing voice to tell their story.

Now Seamab is about to launch a major new fund raising campaign which aims to rebuild their school.

The current premises -a rather odd shaped building set in the Kinross-shire countryside – was originally built as a private home.

Pro-bono

Purcell architects of Edinburgh are already working on a pro-bono basis to redesign the building with other pro-bono support recently coming from the likes of Santander, CR Smith and SGN.

And Seamab, whose patron is former MSP and Presiding Officer George Reid and his wife Daphne, hope Courier readers will get behind the fundraising efforts.

Seamab fundraiser Susie Williamson, originally from Cupar, says: “We will be launching our Pocket Money campaign in late summer under the tag line ‘Small Change for a Sea Change’.

“It will be centred around the basis that most of us as adults have memories of receiving pocket money as children. There’s a big nostalgia attached to many of us about that.

“Our children at Seamab don’t necessarily have those memories. So what we will be doing is asking people to send us their pocket money memories with a donation.

“What many adults received as pocket money when they were young might buy you a coffee or a piece of cake now. Yet that money is worth so much more to the children at Seamab.”

In addition to building a new school, Seamab hope the campaign will also raise their national profile.

“As a national charity, we would like to see Seamab become a household name – standing for children who have been through terrible experiences but turning it into something more positive than that, “ adds Susie.

For more information go to www.seamab.org.uk