The life of a Dundee aviation pioneer who might have beaten the Wright brothers to flight is being celebrated.

Preston Watson – thought by some to have been the first true aviator – was said to have made several flights over land near Errol 115 years ago, in August 1903.

The claims were backed only by circumstantial and anecdotal evidence including that of Preston Watson’s older brother, James Y Watson that the machine was actually a powered aeroplane.

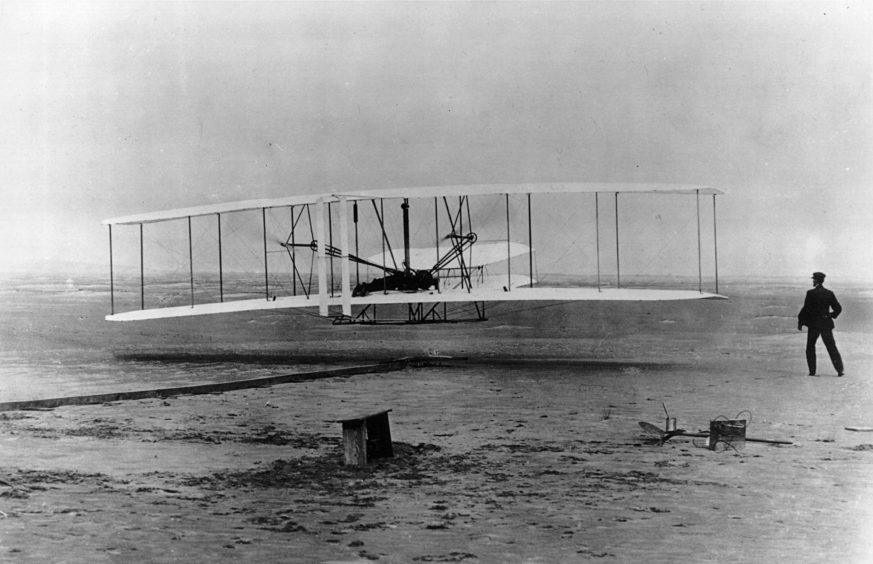

Watson’s apparent flight on the banks of the Tay is said to have taken place five months before the Wright brothers made what is now generally accepted to have been the first manned flight of a heavier-than-air powered aeroplane.

Watson’s wire and wood flying machine was hoisted by means of ropes and weights into the trees, catapulted with engines running, and flew some 100 to 140 yards before landing.

Encouraged by his success, Watson went on to build two further planes

Iain Flett from the Friends of Dundee City Archives said: “There’s no sure way now to nail the dates and technical details of Preston Watson’s early work on power but we should still celebrate the fact that he was one of the small international band of brave and resourceful pioneers who somehow took aviation from string-bags in only 12 years to aircraft designed for military use.

“The Caudron G3 he was killed in had only been in operation for a year and at the age of 34 he must have been one of the oldest and most experienced pilots in the Royal Naval Air Service.

“His probably unmatched experience would suggest that the cause of the crash was structural or mechanical failure and not negligence or ignorance.

“He is joined in Western Cemetery by five more airborne warriors from the Second World War, one of whom is listed on the Battle of Britain memorial in London.

“We should continue to salute them all for their courage and professionalism.”

An obsession with flight

Born in 1880, Watson, who studied at Dundee High School, grew up with a strong leaning towards mechanics.

By around 1901 he was obsessed with the idea of building a flying machine and persuaded his businessman father to advance him £1,000 to do just that.

A friend of Watson’s, Bob Melville who farmed at East Leys Farm near Errol in the Carse of Gowrie, allowed him to use a shed where he started work on his first plane.

The claim that Watson beat the Wrights to powered flight did not materialise until nearly 50 years after the Wright Brothers undisputed flight.

James Y. Watson championed his brothers cause for many years.

He went back to Errol and got half a dozen men to testify that Preston Watson took off in a ‘flying machine’ in the summer of 1903.

Watson was never able to tell his story as he died while training with the Royal Naval Air Service in 1915 aged 34 when his plane exploded above Eastbourne.

He was buried with full military honours in the Western Cemetery in Dundee.

TESTIMONIES

Those who testified included John Christie who had been a ploughman on Daleally farm from 1900 to 1906.

He said he often stopped work to watch the plane clearing hedges and fences and was sure the plane had been flying in 1903.

Broughty Ferry man Alexander Robertson also told how, shortly before he had left school in 1903, aged 13, he had guided a pony to help Preston Watson pull his plane from the shed to the flying field.

David Urquhart of Kirriemuir remembered and described exactly how the plane had been launched, using two falling 56lb weights and a blacksmith’s anvil to catapult it into the air after running along greased wooden rails.

However, none of these witnesses could produce any documentary evidence to back up their claims as to the exact dates involved.

The most compelling evidence against the Watsons claim for pioneering honours came from aeronautical historian Charles Gibbs-Smith.

He carried out detailed research into the Scottish claims for a book on aircraft development in 1960.

In 1966, Gibbs-Smith wrote to The Courier repeating his views: “There is no truth in the story of the 1903 flight, and after confronting Mr James Watson with the facts of the case, he wrote to me in 1955 saying, I make no claim that the machine that Preston used in 1903 was a powered machine.”