“Witch” today strikes up a vision of a pointy hat, green skin and a broomstick, sometimes with a black cat to boot.

But hundreds of years ago more than 3,000 people in Scotland were accused of witchcraft and many were burnt at the stake.

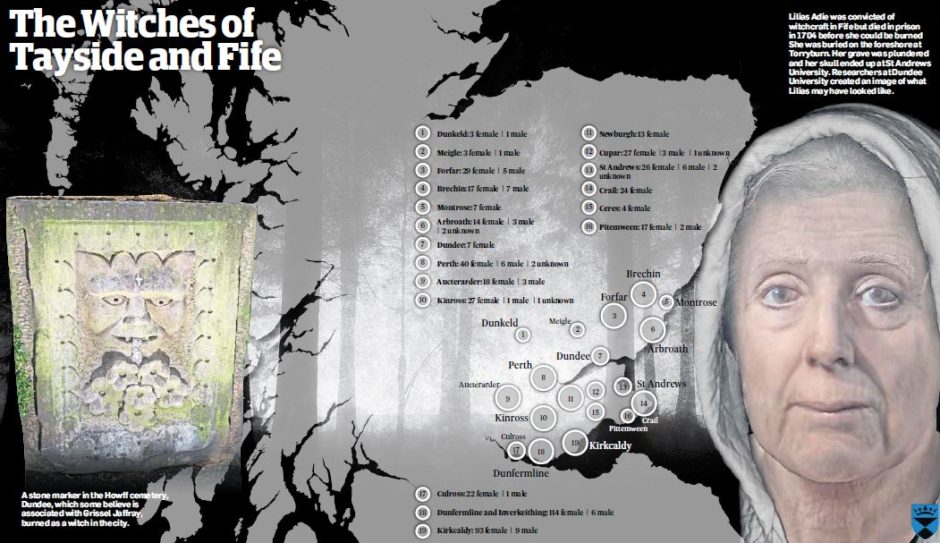

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries 500 male and female alleged witches, one as young as 14, lived in Courier Country.

Some openly admitted their paranormal behaviour, others defended their innocence with their last breath.

Their crimes ranged from charming, poisoning and sorcery to failed healing attempts and cursing. Most were punished by execution or banishment.

Lesser offences were dealt with by the church, usually resulting in the accused being excommunicated.

Now Edinburgh University has created a map of where all of the accused witches in Scotland lived, with details of their misdemeanours and retribution.

It reveals those who were executed, and freed, while the fate of some remain unknown to this day.

Crook of Devon, now a peaceful village in Kinross-shire, was home to 28 accused witches, more than anywhere else in Tayside and Fife.

In the summer of 1662, the settlement was the scene of the killing of a coven of witches.

Of the accused, only one of them, Agnes Pittendreich, escaped the fatal trials, shown mercy as she was pregnant. She was respited and ordered to return for trial after having her baby but there are no records of later proceedings against her.

Those who were less fortunate were strangled by the local hangman and burnt at a mound near the current village hall.

But nobody was safe from capture, regardless of social status. Margaret Hendirsoun of Dunfermline, better known as Lady Pittadrow, died in prison in 1649 after being arrested on a witchcraft accusation.

Witchcraft was a social affair as five middle-class women from Cupar – Margret Wishart, Jonet Staig, Alison Melvill, Jonat Mar and Elspeth Millar – were accused of making a demonic pact in February 1622. All of them confessed but no details of their fate were found in the university research.

A further five – Agnes Robertsone, Janet Robertsone, Agnes Quarrier, Helen Cummyng and Alesoune Hutchesoune, all Dunfermline, were accused of witchcraft and freely confessed to making a demonic pact and the murder of a John Bell. There are no recorded details of any trial or execution.

According to records about Katharine Grieve from Dunfermline, she claimed another witch invited her to her house where they had a pint of ale and cake with the devil.

Agnes Hendrie of Kirkcaldy was also close to the devil. In 1674 the widow said she turned to the devil “in despair of her poverty”. The devil then marked her in a “privy place”. She was executed the following year.

Another widow, Jonet Hendrie, claimed the devil used her “in the manner of the beast”, while Katherine Potter confessed to carnal relations with the devil, branding him “cold as ice”.

One Perth man, David Roy who worked as a cook in 1601, turned his hand to witchcraft in a bid to seduce his employer’s daughter. He consulted a witch and used potions made of his “awn natur” for her to consume.

But there is also evidence to show witchcraft was used for good as a handful of “white witches” made an appearance on the map. A farming couple from Forfar, Giles Chalmer and George Fraser, used an enchantment to make their oat field more productive. This was not without malice, as it thought the purpose was to make theirs more successful than their neighbours. They were summoned to the Privy Council in Edinburgh but there are no trial records.

One white witch, Alexander Drummond from Auchterarder, claimed to be able to cure “all but sudden death”. He caused a stir among church elders when he said he was more powerful than ministers because he could give health.

John Brughe, from Kinross, worked as a professional healer in the 1640s but his career took a sinister turn when he was accused of being a witch. As an act of revenge, he jeopardised baptismal covenants, as well as digging up corpses and using the flesh to harm people. He was found guilty after a trial and executed in 1643.

One of the most notorious witches was Helen Guthrie from Forfar, described as a spiteful woman who boasted of supernatural powers to terrify her neighbours.

When she thrown into Forfar Tollbooth to await trial, Guthrie did not go quietly. She immediately pointed the finger at other women in the town, accusing them of flying on broomsticks, cannibalism and receiving stipends from His Satanic Majesty.

She spun out the accusations over the course of a year, delaying her burning. Many of the women put in the frame by Guthrie were put in branks, iron cages placed over the head with a spike protruding into the mouth. This helped ease many a confession from the 22 women burned as witches in Forfar.

Guthrie was executed on November 14 1662 and there was a bit of a party atmosphere about the town, according to burgh records.

Another mystery comes in the shape of Margaret Merchant, who confessed in 1650 to meeting the devil at Lucifer’s Loch, said to be in Brechin, but the location of the loch has not been confirmed.

The last person to be legally executed for witchcraft in Britain was Janet Horne in 1727. She and her daughter were arrested in Dornoch in the Highlands and sentenced to be burnt at the stake. Her daughter escaped but Janet was stripped, smeared with tar, paraded through town and burned alive.

Missing from the map is Maggie Wall, whose name features on the only monument of its kind in Scotland dedicated to a single witch.

The memorial, which sits by the roadside around half a mile south-west of Dunning, has the words “Maggie Wall burnt here 1657 as a witch” written in white letters.

It is not featured in the resource as there is no evidence that Maggie even existed, never mind that this was the place of her death.

Some have suggested it was built by a local landowner who had been having an affair while others believe it may be linked to the executions of a group of women from Dunning who were tried for witchcraft in the 1660s.

It has achieved notoriety through its connections to the Moors Murderers Myra Hyndley and Ian Brady, who visited the cairn in September 1965, having already killed four children.

In May last year 22-year-old Annalise Johnstone’s throat was slit at the monument. Twelve months later, a jury found the murder case against her brother, Jordan Johnstone, not proven.