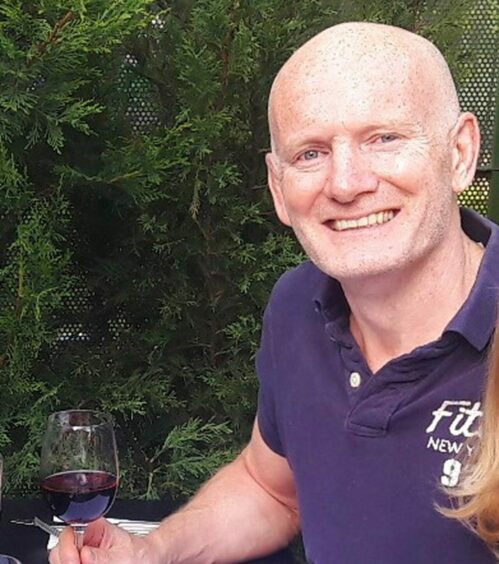

Michael Alexander speaks to the author of a new book who thinks SAS founder Sir David Stirling should be regarded as a ‘phoney major’.

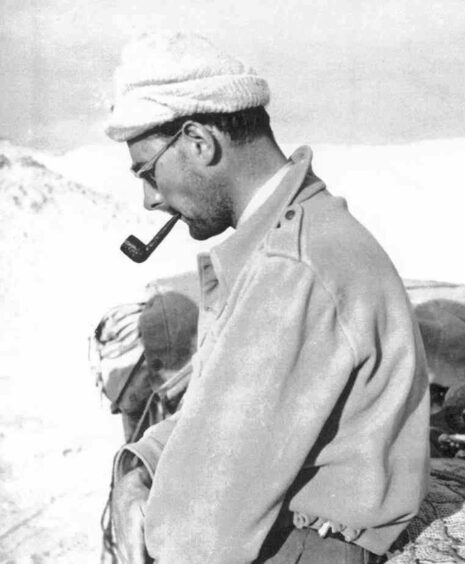

He was the maverick Scots aristocrat – nicknamed the Giant Sloth – credited with founding one of the world’s most famous military units.

Sir David Stirling’s formation of the Special Air Service (SAS) in the North African desert in the summer of 1941 created a new way to hit back at German and Italian forces from behind enemy lines.

The 6 feet 6 inches tall gambler, innovator and legend is remembered as the father of special forces soldiering.

But was the Perthshire-born officer really a military genius, or was he in fact a shameless self-publicist who manipulated people, and the truth, for his own ends?

Analysis of character

It’s a controversial question posed by best-selling writer, historian and TV consultant Gavin Mortimer in his new book ‘David Stirling The Phoney Major: The Life, Times and Truth about the Founder of the SAS’.

In the biography, Mortimer analyses Stirling’s complex character: the childhood speech impediment, the pressure from his overbearing mother, his fraught relationship with his brother, Bill, and the “jealousy and inferiority” he felt in the presence of his SAS second-in-command, Paddy Mayne.

Stirling received a knighthood and plaudits from military forces around the world before his death in 1990 aged 74. Mortimer credits him with being “physically brave and charismatic”.

However, drawing on interviews with SAS veterans who fought with Stirling, and examining recently declassified government files, Mortimer concludes that while Stirling was instrumental in selling the SAS to Churchill and senior officers during the Second World War, it was Mayne who really carried the regiment in its early days.

David Stirling, he says, was at best an “incompetent soldier and at worst a foolhardy one, who jeopardised his men’s lives with careless talk and hare-brained missions.”

“I would say that I am rehabilitating Paddy Mayne who has really had his character assassinated in various books and TV programmes amid a nasty snide whispering campaign,” says Gavin in an interview with The Courier.

“One can feel a degree of sympathy for Stirling because he was an ideas man and he was someone who found himself in a situation ie commanding officer of the SAS, who clearly wasn’t cut out for this role.

“But it was Paddy Mayne who was to all intents and purposes the leader.

“When Mayne died, Stirling saw his opportunity. He returned from his self-imposed exile in southern Africa and staked his claim to be the ‘father’ of British special forces.”

Research began with Paddy Mayne

With an interest in rugby, Gavin Mortimer first got interested in the wartime SAS more than 20 years ago through research he was doing into his hero Paddy Mayne.

In the late 1930s, Mayne played rugby for Ireland and the British Lions.

As a young writer in the late 1990s, Gavin thought about writing a biography on him.

During the course of his research, however, he read a book he regards as the best memoir of the SAS ever written, Born of the Desert by Malcolm James, who was the SAS wartime medical officer.

Through James, who lived in Oxford at the time, he got to know another original SAS member Johnny Cooper.

It was Johnny who suggested he write a history of the wartime SAS from the perspective of the men rather than the officers.

Johnny introduced him to the regimental association, and through that introduction, he was contacted by around 70 wartime SAS veterans, including several in Scotland, who wanted to tell their story.

Gavin says it’s taken him a while to examine in more detail the wartime SAS and particularly the role of David Stirling.

The Phoney Major is a play on words of David Stirling’s 1958 memoir The Phantom Major – written three years after Mayne’s death.

Who was David Stirling?

Born in Keir House, Perthshire, in 1915 into an aristocratic Scottish family with a proud military heritage, David enjoyed the freedom of the Scottish Highlands as a child, where he honed his skill as a hunter.

He was dubbed the “Phantom Major” by German Field Marshal Rommel, and Britain’s commander Field Marshal Montgomery described him as “mad, quite mad”.

He was rumoured to have personally strangled 41 men.

He was finally captured by the Germans in 1943. He escaped and was recaptured by the Italians. After four more escape attempts he was sent to the notorious Colditz prison where he spent the rest of the war.

Later he formed a private military company working in Gulf states.

What strikes Gavin when he looks back at his interview notes now, however is how the now mostly deceased wartime SAS men were all “in awe” of Paddy Mayne.

The other interesting thing, he says, is how they paid tribute to David’s older brother Bill.

They described him as an “intelligent man” who was “under-rated and unsung”.

‘Lounge lizard’

“David was, to use the vernacular of the time, a lounge lizard or a loafer,” says Gavin.

“He was known in the Scots Guards as the Giant Sloth.

He was lazy and he preferred spending his time in the posh clubs and gambling dens of London.

“It was Bill throughout life really who took David under his wing.

“David like a lot of middle sons born into land owning families was at a bit of a loss.

“Bill had inherited the estate and the money and the power and the status that came with it in 1932 when their father died.

“And so this myth of David Stirling founding the SAS by himself was just that – a myth. It was Bill really who was the intellectual.”

Gavin describes Paddy Mayne as the “physical force” of the SAS in World War Two and Bill Stirling as the “intellectual force”.

David Stirling, by contrast, was the “frontman”. He was “quite charismatic and quite forceful and a very good salesman”.

However, he was a novice, Mortimer says, when it came to identifying Britain’s need for a small but highly trained guerrilla force.

Did David Stirling embellish his past?

“How can I put it politely, but when I delved into David Stirling’s life outside the war and what had been written about him in his two biographies, there’s a lot that he embellished,” says Gavin.

“He claimed he went to America in 1938 because he wanted to climb Mount Everest. He didn’t.

He was sent to America by his mother and Bill who were at their wits end because he was so aimless. He was actually ranching. They had a family friend in El Paso.

“He also made up his time at Cambridge. He said he spent most of his time gambling at Newmarket.

“In fact he was only at Cambridge for three terms, none of which coincided with the racing season.

“He left Cambridge because he quit which was a feature of his life when things didn’t go the way he wanted. He would often walk away.”

Gavin says David Stirling tried to portray himself in later life as a kind of “devil may care buccaneer – a gambler”.

Another fabrication, he says, was the claim he spent a year and a half in Paris in the 1930s being taught by the famous French painter Andre Lhote.

However, the real David Stirling, he claims was “immature and undisciplined and insecure and just purposeless”.

Death of Paddy Mayne

Gavin claims that what allowed Stirling to “pull off this deceit” was the death of Paddy Mayne in a car crash in 1955.

“In the 10 years after the war, David had spent most of his time in Southern Africa, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe),” says Gavin, “and he had nothing to do with the SAS.

“But the death of Paddy Mayne meant he could rewrite the history of the SAS because there were really no officers left to challenge his version of events.

“There was of course Bill Stirling. But because he recognised David’s flaws and how lost he was after the war, he was quite happy to let David take the plaudits.

“The joke during the war was that SAS stood for ‘Stirling and Stirling’.

“There were numerous examples in the 1940s and the years immediately after when Bill and David were referred to as the co-founders of the SAS.

“But Bill had a business career, was married with a young family: he was everything that David wasn’t. Discrete, modest, unassuming.

“But within the SAS itself there was no one to challenge David’s version of events.

“That’s why he was able to get away with it really. He came from the upper class. He was very much an establishment man.

“The Stirlings were friends of the royal family. He was a very powerful figure and no one was wishing through his lifetime to challenge his version of events.”

‘Mystique’ of the SAS

Gavin says there’s no doubt the “mystique” of the SAS also helped David Stirling re-write history.

What changed the whole image of the SAS, however, was the Iranian embassy siege in 1980.

The TV images of black clad SAS men abseiling from the roof and forcing entry through the windows.began what Gavin describes as “the cult of the SAS”.

“There’s a mystique that has grown up around them,” he says, “and Stirling in the last decade of his life was able to jump on that bandwagon.”

*David Stirling The Phoney Major: The Life, Times and Truth about the Founder of the SAS by Gavin Mortimer is published by Constable, £25, ISBN 978-1-47213-458-5.

Conversation