Two decades since its launch as a forum to pool information and advice, Mumsnet has become one of the biggest parenting websites in the world and regularly attracts more than 10 million visitors a month.

But while many women – and some men – log on to talk pregnancy, parenting and all things child rearing, many stick around for the politics.

The site has become a powerful campaigning tool and has helped established real change across a number of previously underrepresented areas, even spearheading the push to have marketing companies kicked out of maternity wards.

It also regularly hosts make-or-break webchats with leading politicians, including a minor debacle in 2009 – dubbed ‘biscuitgate’ by the press – when then-prime minister Gordon Brown was accused of dodging questions about his favourite biscuit.

Since then, everyone from Nicola Sturgeon to Boris Johnson has appeared to woo voters on the site, with debates on Scottish independence and Brexit also helping to pad out the more than 45.5 million words written on its talk boards every month.

As Professor Sarah Pedersen, an expert in communication and media at Aberdeen’s Robert Gordon University, puts it in her new book, The Politicization of Mumsnet, many of the site’s regular visitors “came for the babies – stayed for the feminism”.

Her book delves into the way politicians have attempted to use the enormous platform to connect with its largely middle-class female user base, who are seen as a valuable political asset because of their tendency to “float” between parties.

Professor Pedersen believes the site has been able to parlay that interest into support for key Mumsnet causes, many of which – such as calls for better miscarriage care – began as grassroots campaigns and were then taken up by the site.

However, Mumsnet has also come in for sustained criticism and advertiser walk-outs for allowing a “safe space” for fiery discussions over proposed changes to the Gender Recognition Act, a subject that has led to allegations of transphobia.

Controversary around topics discussed on the message boards has seen opponents go to sometimes extraordinary lengths to silence the debate, including a naked protest by Fathers for Justice against advertiser Marks & Spencer in 2012 and a hoax call that saw armed police sent to the home of site co-founder, Justine Roberts.

Professor Pedersen believes Mumsnet’s popularity is partly down to it being a place where women can talk freely about politics without being drowned out by male voices or being subjected to the nastier side of other social media platforms.

She said: “I think it’s really important to emphasise that Mumsnet has always had political debate. I think that when women become parents this is the time when the fact we’re not in a gender-equal world really becomes clear to them.

“When you become a parent, you suddenly realise about things to do with maternity leave and childcare costs, and the brutal realisation that there is not equality dawns on you, I think, often for the first time.”

Professor Pedersen compares the forums to the letter pages of Edwardian newspapers – a previous research topic – where women, often using pseudonyms, entered a political sphere dominated by men to discuss marginalised issues, such as voting rights.

Mumsnet also allows a degree of anonymity by allowing users to pick their own usernames and a previous study by Professor Pedersen found the minority of men on the site often adapt their writing style or avoid certain topics to fit in.

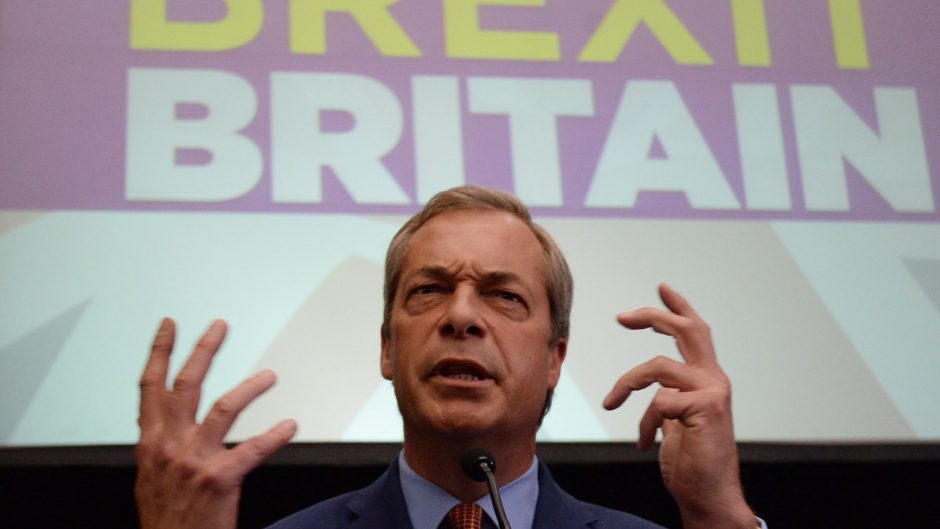

The platform allows politicians to speak to site users directly and while some have prepared well and used the opportunity wisely, others – such as former UKIP leader Nigel Farage – came off badly in the exchange.

‘It’s an opportunity for a dialogue’

Professor Pedersen said the unique nature of the site means those looking to drum up support or highlight their new campaign should take the time to research how Mumsnet works – and probably leave out the now well rehearsed biscuit anecdotes.

“I’m always amazed when I’m reading these webchats and it’s very clear that the politicians or their researchers haven’t gone on previously,” Professor Pedersen said.

“The chats are often up for a day or two before and you would think they would go along to see the five or six issues that keep being repeated, and to have already written answers to some of those questions.

“The other key thing is that a lot of politicians use it to broadcast, not to engage or have a conversation. It’s an opportunity for a dialogue but it’s rarely used in that way.”

Perhaps politicians would do well to remember the words of Robert Campbell who, after users took on his advertising agency over a controversial campaign in 2010, said : “Don’t mess with Mumsnet. It is like wrestling with an octopus.”