As St Andrews University’s world-renowned Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence launches its 25th anniversary celebrations, Michael Alexander learns more about how the violence of ‘killing strangers’ became modern.

The director of Europe’s oldest research centre on terrorism is “extremely worried” about the prospect of a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland in the event of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit.

Dr Tim Wilson, who heads St Andrews University’s world renowned Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV), said the re-hardening of the border would be an “absolute gift” to so-called dissident Republicans.

And he is “extremely worried” about the “levels of ignorance about the situation at the highest levels of the British government”.

“I’m a realist pessimist,” said Dr Wilson.

“I’m extremely worried by the outlook on the border. We know from the long history of Northern Ireland that apparently violent conflict can die down and then reawaken. We’ve seen that in the 20s, 30s, 50s and 60s onwards.

“I’m extremely worried about the levels of ignorance about the situation at the highest levels of the British government.

“To a certain extent they have been forced to engage with it, but the actual intuitive understanding of how fragile the situation is seems to be beyond the top tier of the Cabinet.”

Oxford University educated historian Dr Wilson, whose interest in political terrorism was awakened while running an after-school club in North Belfast during the 1990s, spoke to The Courier to mark the official launch of the 25th anniversary of the CSTPV.

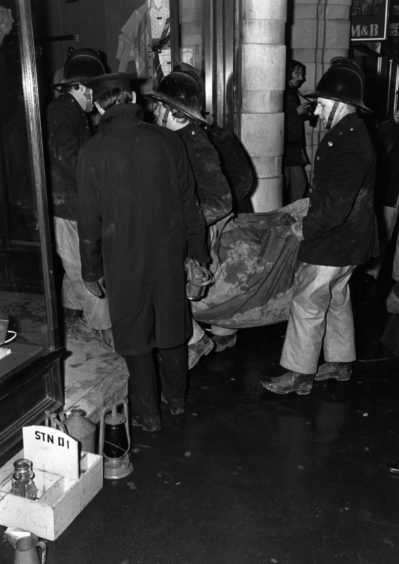

Dr Wilson recently gave a lecture at St Andrews University called ‘Killing Strangers – How Violence Became Modern’ that will examine the origins of our contemporary terrorism crisis.

Over the past 25 years, the CSTPV has consistently remained at the forefront of cutting-edge research into the causes and consequences of political violence. It has built both a global reputation and close links with ‘practitioner’ communities: whilst rigorously retaining its academic independence.

To mark this quarter century, Dr Wilson’s keynote lecture sought to shed light on how we have come to live in these terrorism-dominated times. For example, how did we get to a point where every time we travel by plane or on underground trains, official announcements remind us that total strangers might slaughter us?

“It’s really about asking why does the violence we see around us take the forms it does?” he said.

“If we stand back, it’s actually very very strange to live in a society where every time you catch the London Underground, or get on a plane at Edinburgh Airport or wherever it is, you will be reminded that total strangers might slaughter you or do terrible things to you, and that we sort of accept that! “It’s like urban pollution – we just accept that’s part of urban living.

“But it’s actually a very very weird idea. Historically, most violence – politically or not – came from relationships that have gone toxic or gone intimate. You ask any CID detective in any police force – they’ll always look for a relationship if they can find a murder victim or whatever.

“The idea that total strangers might kill us for some cause which we may know little or may not even have heard much about is a very strange idea and that’s what I’m trying to ask: where on earth has that come from?”

Dr Wilson said the short answer is that it’s deeply bound up with a whole set of processes which go to make up the modern world. Technology, for example, can distance people from the consequences of their actions.

Yet if an action can get the attentions of millions of people simultaneously, then that in itself is a form of influence which can spur further outrage and shocking behaviour including political violence.

“Often we have this assumption that violence is somehow barbaric and medieval and somehow a reflection of a failure (in our society)”, continued Dr Wilson.

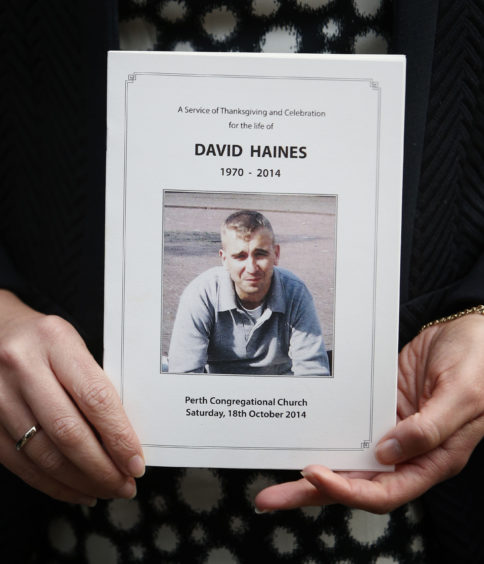

“(Former Prime Minister) David Cameron talked a few years ago about beheadings being medieval and belonging to the Dark Ages. That’s a very common assumption. I’m trying to offer the rather disturbing counter view that perhaps in some way this type of violence belongs to our age, belongs to our society.

“We can’t just externalise it and say it’s somehow freakish or left over from medieval society. It’s not.”

Dr Wilson, who joined the CSTPV in 2011, said the centre was testimony to the vision of its founding fathers Bruce Hoffman and Professor Paul Wilkinson in 1994 – a time when everyone thought ethnic cleansing was the main concern and that perhaps terrorism was “yesterday’s news and a Cold War phenomenon”.

“The centre has had a lot of back up from the top of the university and I’m proud and pleased to say that,” he said.

“The founding fathers took the long term views, and I think they have been thoroughly vindicated both in seeing that terrorism would be here to stay in one form or another.

“The distance between St Andrews and both Edinburgh and London also matters. It’s a good place to take a long cool hard look at human nastiness broadly defined.”