Michael Alexander explores the history of Queen Margaret of Scotland – later canonised as a saint – who married King of Scots Malcolm III in Dunfermline 950 years ago this Easter Monday.

She was the pious Roman Catholic who established a ferry across the Firth of Forth for pilgrims travelling to St Andrews that gave the towns of South Queensferry and North Queensferry their names. More recently she even inspired the title for the Forth’s newest road crossing.

But 950 years after Hungarian-born exiled English princess Margaret married Scottish King Malcolm III in Dunfermline on Easter Monday 1070, the legacy of Scotland’s 11th century Queen and canonised saint is so much more.

There’s no doubt that one of her most significant legacies was the Canmore dynasty which she and her husband founded. Of their eight children, four sons – Edmund, Edgar, Alexander and David – became kings of Scotland. A daughter Matilda also became Queen to Henry I of England.

But according to Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs, Margaret also changed the social, cultural, religious and economic trajectory of Scottish history.

“She single-handedly Romanised Scotland, introducing the Continental Benedictine Order to Scotland and reforming Scotland’s ancient Gaelic identity – casting aside it’s Celtic traditions and bringing it into line with Europe,” said Mr Speirs.

“The year 1070 is the date that Margaret came finally to Scotland in the aftermath of the failed English rebellion of 1069, probably landing at Inverkeithing although exactly where she landed in the Forth estuary is not recorded.

“This followed a meeting between Malcolm and Margaret and her family at Monkwearmouth in Co Durham, when they had taken ship for Flanders.

“They were driven north instead by storms and ended up back in Scotland.

“For commemorative purposes, however, it wasn’t her first time in Scotland, for she had come with her brother and extended family, escorted by Cospatric Earl of Northumbria, in 1068.

“On that occasion, Malcolm had counselled them to make their peace with William the Conqueror and return to England. She came north in 1068 and doesn’t stay. The year 1070 was to be the moment of permanent settlement through her marriage to Malcolm.”

Born around 1045, Saint Margaret of Scotland, also known as Margaret of Wessex, was the sister of Edgar/Eheling – the short reigned and uncrowned Anglo-Saxon King of England. Her family fled to Scotland following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. When she married King Malcolm III of Scotland, she became Queen of Scots.

While Easter Monday 1070 is historians’ accepted date of their marriage – and would “make sense” as it’s the most important day in the Christian calendar – Mr Speirs said that having double checked all the contemporary source material, there is actually “absolutely no indication” of the time of year the union took place.

It’s not even really possible to narrow it down to a window of a few months as the available source material just isn’t detailed enough, he said.

“Indeed, there’s a realistic possibility that they married in 1069 but most informed historians, whilst acknowledging this possibility, prefer a 1070 date,” he added. “The limited available historical evidence indicates they were married by the end of 1070.”

Quoting the work of Margaret’s biographer Turgot of Durham, Dunfermline Historical Society has explained how within two years of her marriage to Malcolm, Margaret had built a priory in Dunfermline.

The priory was dedicated to the Holy Trinity and to carry out the religious duties, she had monks sent to Scotland from Canterbury.

Religious life in Scotland was previously led by Culdee monks, who, for around 500 years had followed the teachings of St Columba.

Amid suggestions the Culdee form of religion had “become stagnant and duties were performed mechanically”, Margaret, who had been taught the Roman Catholic religion, set about attempting changes.

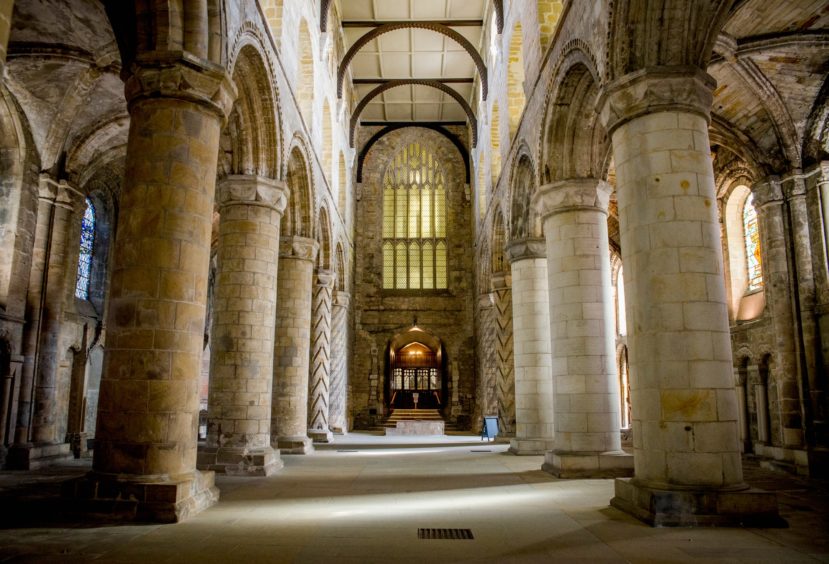

Today, substantial remains of the great Benedictine priory founded by Queen Margaret in the 1070’s and elevated to abbey status by David I in 1128, still stand in Dunfermline. It replaced an older 10th-century Culdee church on the site.

When she died in Edinburgh Castle on November 10 1093 – just days after her husband and her son Edward were killed at the Battle of Alnwick – her body was taken to Dunfermline for her burial.

When she was canonised in 1249 by Pope Innocenti IV – a result of her renowned charity work, helping of the poor, her alleged ‘miracles’ and perhaps as a thankyou from Rome for Scotland’s support during the Crusades – the church was enlarged again to include her shrine.

The western part of the building is the nave of the Abbey church, and the eastern end serves as the parish kirk.

But Mr Speirs said that from an archaeological perspective, there is so much more to celebrate. He also feels the history deserves greater recognition to put Dunfermline on the map.

“We have Margaret’s shrine in Dunfermline, Margaret’s Stone in Dunfermline and Margaret’s Cave in Dunfermline,” he said.

“We also have photos of the tiny church in which she was married. It now lies underneath the 1140s Dunfermline Abbey nave – but it was excavated in c.1920 when the floor of the abbey nave was lifted.

“Her miracula – the list of her miracles submitted to Rome as part of her canonisation bid in 1249 – was discovered only recently in the Royal archives of Spain.

“There’s even one of her personally owned illuminated 11th century gospel books.

“The book is described in Turgot’s early 12th century Life of Queen Margaret and was rediscovered only in the 19th century.

“It’s now in the Bodleian. Turgot – her confessor – wrote a life story of her and describes the miracle of this gospel book being dropped in a river but when Mags went back to recover it, it was undamaged!

“We also have a relic, her scapula, preserved in Dunfermline even if her head shrine and birthing gown etc can no longer be traced.

“The degree to which she single-handled changed Scotland is truly incredible.

“The amount of reliable contemporary source material for her is also amazing.

“She was buried at Dunfermline and formed the centre of the second biggest medieval pilgrimage cult in Scotland.

“The story of her devotion, the influence on her husband and on Scotland in general, is amazing.

“Her birthing gown was used by every Scottish Queen from the 11th century up to the time of Mary Queen of Scots and of course she had sons who were kings of Scotland and a daughter who was Queen of England.

“Yet, if you go to Dunfermline Abbey, the finest example of Scoto-Norman architecture in Scotland, essentially a massive shrine to her built by her son David I, there is almost no mention of Margaret – or the other 21 royals buried in what was the medieval royal mausoleum of Scotland. Why?

“Everything about the story is amazing.”

The Courier told last year how experts were using 3D scanning technology to discover more about the life of Margaret and how her scapula bone – a reliquary in the possession St Margaret’s RC Church in Dunfermline – was venerated.

Glasgow University archaeology student Lauren Gill, from Cardiff, and Martin Lane from Cardiff Metropolitan University visited St Margaret’s RC Memorial Church last March to carry out the study of the bone fragment which has been housed in a crystal reliquary since 1886.

From canonisation in 1249, she lay intact in her Dunfermline shrine until the 16th century when Mary Queen of Scots asked for her head to be sent to her, to bring her help as she gave birth to her son who would become King James VI.

Her head was then taken to a Jesuit College in Douai, France, but was never seen again after the French Revolution.

As the Reformation gathered pace and threatened to destroy Catholic churches, the remainder of her body was secreted away in the 16th century, ultimately being taken to Escorial Monastery by Philip II of Spain.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that Bishop James Gillis of Edinburgh sought permission from Pope Pious IX for a relic to be brought to Scotland.

They sawed a piece of the shoulder bone off and they sealed it with the seal of the Escorial.

Bishop Gillis brought it back to Scotland to be placed in St Margaret’s Convent in Edinburgh but when the convent closed it was moved to St Margaret’s RC Memorial Church in Dunfermline in 2008 where it has been since.