It was the single-seat vehicle which was billed as the future of transport.

In 1985, British entrepreneur Sir Clive Sinclair unveiled the £399 electrically-powered pedal car the C5.

He had invented pocket radios, pocket TVs, electronic watches, and Britain’s biggest-selling home computers, which were manufactured at Timex in Dundee.

Dundee got its first glimpse of the three-wheeler C5 when it went on display at the Hydro Board showroom in Whitehall Street after electricity board shops were selected to display the vehicle.

However, the contraption’s launch in Dundee 35 years ago was an unmitigated disaster.

The Courier’s then motoring writer Ian Lamb tested the C5. Police closed off two major junctions on the circular route he was to be taking but the event ended in disarray.

The drive chain fell off twice and Mr Lamb travelled only a few yards.

The vehicle was then carried ignominiously back into the Hydro Board showroom for repair.

Huge interest in the C5 in Dundee

“It was a total disaster,” recalled Mr Lamb from his home in Arbroath.

“There was huge interest in the C5 in our area because of Sir Clive Sinclair’s connections here so, as I was motoring correspondent, I was asked to arrange to drive one.

“I spoke to the Hydro Board shop manager and he was happy to let me have a shot of the one in the shop on display in the window.

“I went down to Whitehall Street at lunchtime and found they had decided my ‘test drive’ would be up Whitehall Street, right into the Nethergate, right again into Crichton Street, then Whitehall Crescent and back to Whitehall Street.

“To ensure nothing untoward happened, they had also arranged for two policemen to be at the junctions onto and off Nethergate to stop traffic to allow me to do the circuit.

“Shop staff carried the C5 on to the road, and a large crowd built up very quickly and surrounded it.

“The manager went over the controls with me, signalled to the bobby at the top of the street, got the crowd to clear a path and off I went – all of 15 feet before the drive chain dropped off.

“Embarrassed, they re-attached and tightened it. We had a second start and the same thing happened.

“The manager decided this was doing potential C5 sales no good whatsoever, the two bobbies were stood down and the ‘vehicle’ was carried ignominiously back into the shop.”

Electric car dream

Sir Clive had an interest in electric vehicles for a long time and wanted to develop his own.

Early research and development had started in the early 1970s at Sinclair Radionics.

In March 1983 Sir Clive sold some of his shares in Sinclair Research to raise £12 million and form a new company, Sinclair Vehicles.

The contract to assemble the C5 was given to the Hoover Company, who carried out manufacture at their washing machine factory in Merthyr Tydfil, Wales.

Sir Clive estimated well over 100,000 cars would be sold in Britain in 1985 alone.

Damning report from British Safety Council

The C5, which was just six feet long, and no wider than a bicycle, could be driven by anybody over 14, without a driving licence, road tax or crash helmet.

Sir Clive claimed the open-top single-seater, which could run 1,000 miles for the same price as a gallon of petrol, would add to safety on the roads.

The C5 received mixed reviews after going on sale before the British Safety Council issued a highly critical report on the vehicle.

Out of 14,000 made, 5,000 were sold before manufacturer Sinclair Vehicles went bust.

Releasing a vehicle with no weather protection was not a particularly good idea and the C5 now enjoys the dubious distinction of Worst Gadget of All Time, ahead of Betamax videos and pizza scissors.

Clive Sinclair: A man ahead of his time

Sir Clive Sinclair was a man ahead of his time.

Born near Richmond, Surrey, his middle-class family were unconventional.

The oldest of three, Sir Clive had a happy childhood but he didn’t really get on well with other children and preferred the company of adults instead.

His father and grandfather were both engineers, and Sir Clive’s bedroom was often a forest of wires and circuit boards.

He even built a miniaturised communications system for his hideout in the woods.

During his teens, he rejected the chance to go to university because he said “there’s nothing a university can teach me I don’t already know”.

When he was 18 and working as a technical journalist, Sir Clive came up with his first professional invention – The Micro Kit radio circuit.

To help sell it, he founded his first company, Sinclair Radionics, and within three years was married to wife Ann and selling The Sinclair Microamplifier Radio.

Big break

His break came with the invention of The Sinclair Executive, the world’s first pocket calculator which won a host of design awards.

Sir Clive visualised that all technological products should be “the size of a cigarette packet”.

It inspired his next invention, the world’s first LED digital watch (The Black Watch).

Its futuristic design and unconventional look was too far-fetched for some and centrally-heated offices and nylon carpets affected its ability to work.

One day in the late 1970s, Sir Clive had a brainwave while watching one of his children play with a Tandy Radio Shack.

“I could see how exciting these were for young people,” he said.

“But the cost of them was prohibitive.

“I felt sure that if a working computer could be made for a reasonable price, there was potentially a mass market for it.”

Sales went through the roof

He said he was sure everyone in the modern world would have a computer in their home by the year 2000.

Sir Clive invented one and 50,000 were sold, at around £100 each, proving there was a future for home computers.

Two years later, he came up with the ZX Spectrum and sales went through the roof.

They were manufactured at the Timex plant in Dundee.

His next big hope was a mini flat-screen TV which he thought was the first of its kind.

Sadly for him Sony’s Watchman beat him to the finish line by 18 months.

Knight of the realm

Not to be outdone, he was named Businessman Of The Year in 1983 and knighted for his services to British Industry.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher gifted a ZX Spectrum to the then-leader of China.

Then, suddenly, it all went sour after the Sinclair C5 was halted following derisory sales.

The huge financial losses forced Sir Clive to sell the Sinclair name and the rights to his computers to Sir Alan Sugar’s Amstrad.

He said: “It wasn’t a blow to my confidence. You can’t win them all.”

Sir Clive visited Timex in 1983

Timex in Dundee was producing a computer every four seconds at its Camperdown plant in 1983.

The Spectrum offered colour graphics for the first time.

The Spectrum’s predecessors the ZX80 and ZX81 had both sold well to computing enthusiasts, but it was the ZX Spectrum that turned home computing into a mass market hobby.

The first ZX Spectrum was launched on April 23 1982 in two models – a version with 16 kilobytes of memory, selling for £125 and a 48k model for £175.

There was no monitor and computers were connected to a television through the aerial socket.

Like ‘dead flesh’

The original Spectrum was once memorably described as feeling like “dead flesh”.

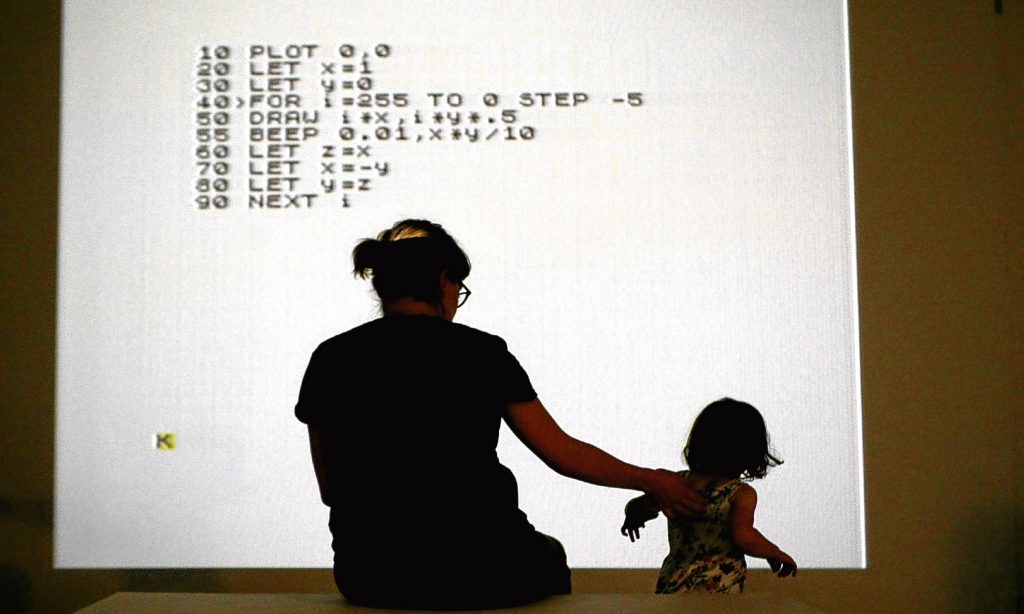

Programmes and games had to be loaded using a cassette recorder connected to the computer or typed in word for word in the computer language BASIC.

Although it was originally only available through mail order, within three months Sinclair Research had a backlog of orders that reached 30,000 as games such as Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy and Dizzy helped to popularise the machine.

Despite competition from higher-powered computers such as the Commodore 64 and the Amstrad, price cuts ensured the computer remained Britain’s most popular model.

In 1983 Sir Clive visited the Timex factory in Dundee and was presented with a special white version of the machine to celebrate the millionth unit sold.

Spectrum stock sold to Sir Alan

Sinclair released several updated versions of the computer that even offered a more professional plastic keyboard.

However, other Sinclair products such as the C5 were proving less successful and under mounting pressure, Sinclair Research sold the rights and remaining Spectrum stock to Sir Alan Sugar’s company Amstrad for £5 million in 1986.

It signalled the end of Spectrum manufacturing in Dundee as Amstrad moved production to Taiwan before the line was discontinued in 1992, no longer able to compete with most powerful computers and consoles on the market.

A generation of “bedroom programmers” creating games for the Spectrum grew up to create the games industry that exists today in Dundee.