She was the Arbroath missionary who was shot and held hostage in Iran for six months until she was rescued by Terry Waite.

Jean Waddell, the one-time organist of St Mary’s Episcopal Church, was considered a “chief spy” during the Iranian Revolution when all westerners were looked on with suspicion.

Shot twice

She was the Anglican Bishop of Isfahan’s secretary in Tehran when two Iranian revolutionary guards burst into her flat, strangled her unconscious, then shot her twice at point blank range.

The shooting made international headlines 40 years ago in May 1980.

The hostage drama which followed made her famous and pitched Mr Waite into the limelight and earned him a ‘trouble-shooter’ reputation.

Miss Waddell, who was a former wartime Wren, spent her childhood in Arbroath.

She left in 1956 in search of “something more worthwhile” than her work as a secretary for a business.

She moved to London and worked as a medical secretary and then for a charity for the disabled.

In 1965 she replied to an advertisement for a secretary to the Anglican Archbishop in Jerusalem.

When she arrived in Jerusalem the city was divided between Israel and Jordan.

The Anglican Cathedral, St George’s, was in East Jerusalem, under Jordan.

During the Six-Day War of 1967, shells exploded all around St George’s, while she and the rest of the staff sheltered in the cellars.

When the fighting was over, East Jerusalem was under Israeli occupation.

The readjustments for those around her were considerable.

In 1977 Bishop Hassan Dehqani-Tafti invited her to become his secretary in Isfahan in Iran.

US Embassy siege

Feelings against the Shah – and his Western supporters – were coming to the boil and, in January 1979, he left the country.

Foreigners began to leave the country, but Miss Waddell and her colleagues stayed on.

In late 1979 when 52 American diplomats and citizens were seized by a group calling themselves the Muslim Student Followers Of The Imam’s Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution and took over the US Embassy in Tehran.

The students’ actions were fuelled by the US admitting the Shah for cancer treatment, and refusing to return him to stand trial for crimes he was accused of committing during his reign.

The moderate Iranian government resigned and the theocratic authorities took full control of the country.

In May 1980, gunmen burst into Miss Waddell’s flat, shot her and left her for dead.

A few days later the son of her boss, the Anglican Bishop in Iran, was assassinated.

She was found by her downstairs neighbours and fellow Church Mission Society members, Diana and Paul Hunt and their two daughters.

Weak from the shooting, she thought death was just around the corner.

They got her to hospital just in time.

After a period of recovery, she was given an exit visa in Tehran to leave Iran but it was blocked in Isfahan.

Spying charges

On August 6 she went to offices in Isfahan with a British Embassy official to clarify issues and was arrested on trumped-up spying charges for which the punishment could be execution.

Back then, at the height of the Islamic revolution, she was blindfolded and moved around various prisons.

She ended up in Tehran’s Evin prison where she was to share a cell for six months with Cynthia Brown Dwyer from Buffalo.

The cell they shared became known as “Jean’s Cafe” because she had a heater and was able to make tea and coffee for the inmates.

Terry Waite, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s special envoy, arrived in December 1980 to negotiate the release of Miss Waddell and her fellow-missionaries John and Audrey Coleman.

A fourth Briton – a businessman, Andrew Pyke, an employee of the Dutch firm Helicopter Aviation Services – was also being held prisoner.

Angus South Conservative MP Peter Fraser gave a speech in the House of Commons in January 1981 where he praised the “outstanding efforts that were made by Mr Terry Waite” during his mission to Iran.

He said: “That mission was undoubtedly fraught with difficulties, but he overcame the obstacles that were obviously there, with what must be a rare diplomatic skill.

“I have no doubt that in no small measure that was due to his deep personal sincerity.

“We should do nothing to imperil the successful initiatives that were taken by the envoy of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

“It is acknowledged that the Iranian authorities seem to be prepared to understand that none of the missionaries is a spy, and we must continue to demand their immediate release from prison.

“No proper charges have ever been made against them, and the documents on which the wild allegations of CIA activity were based have been seen to be nothing but the crudest of forgeries.

“Hopes are still high that my constituent, Jean Waddell, and Dr and Mrs Coleman will be released in the near future, but until they are allowed to return home in safety it is vital that we demonstrate – as we are doing in this debate – that our concern is for them and that we express the wholehearted support for the Anglican Church in its efforts to get these fine people home.”

Arrival back in Britain

With Ronald Reagan now in charge at the White House, the US agreed to unfreeze Iranian assets in return for the release of the 52 hostages being held at the US embassy since November 1979.

Three of the four British hostages were released a month later in February 1981.

Miss Waddell left Evin only to be held for another two weeks, first in a house and then in an old palace.

There she found her fellow-missionaries whom she had believed to be dead, and waited while Mr Waite negotiated their release and that of four Iranian colleagues.

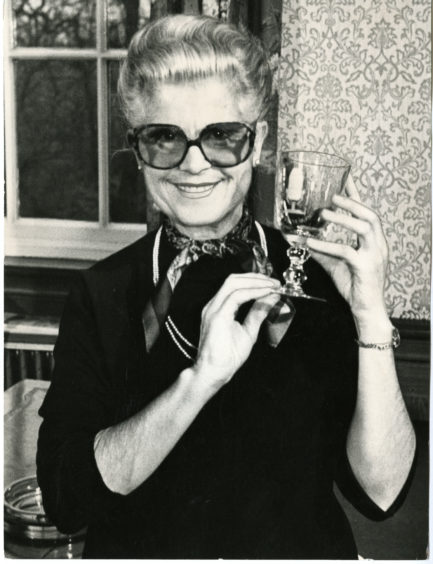

She arrived back in Britain on February 28 to be met at the airport by press and TV reporters.

When congratulated upon her endurance, she insisted that she did nothing.

She said that God did everything.

“When I felt particularly helpless and thought that I ought to be doing something I was always given the words: ‘Stand still and see the salvation of our God’.

“Such quiet and total reliance upon God worked miraculously; fear faded and an inner peace prevailed.”

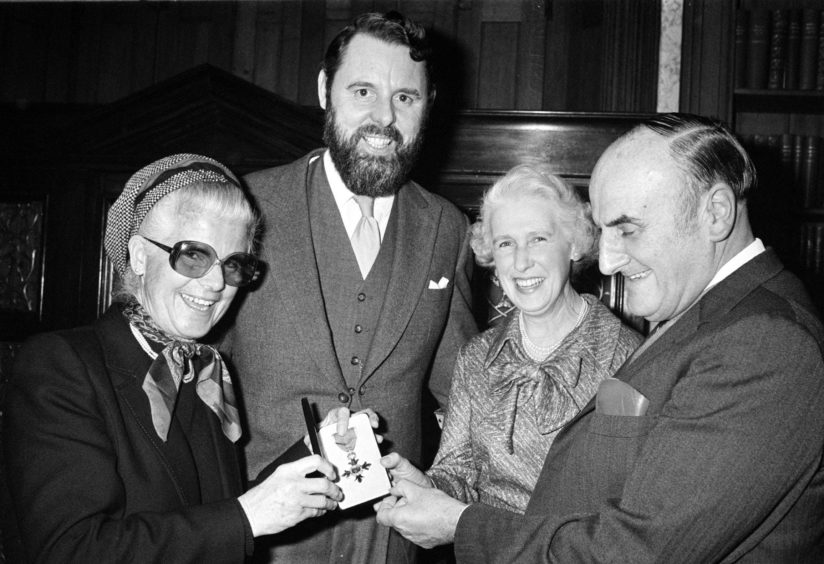

She was elected Scot of the Year in 1981 and received a civic reception from Angus.

She returned to her old job and worked in Basingstoke as secretary to the exiled Dehqani-Tafti.

Andrew Pyke was finally released in February 1982 after being held in an Iranian jail without trial for 17 months.

Despite her travails, Miss Waddell’s love of the Middle East endured and for many years she escorted tours to the Holy Land.

Her experiences also deepened her respect for her Muslim friends and her certainty of the need to work together.

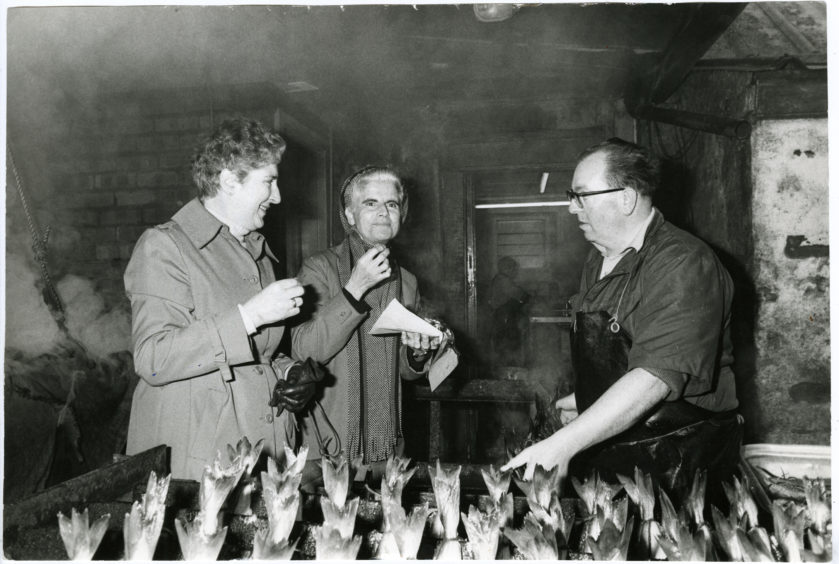

Smokie pancakes

Having never lost her missionary edge, she continued to dedicate time to helping others and returned to her native Arbroath twice a year where she would eat smokie pancakes every day at her sister’s.

She spoke about her experience in captivity which changed her outlook on life during which it transpired that the Iranians had offered to exchange her for tank parts.

“I was expecting to be executed every hour, every day, from the time I was taken to the time I was released,” she recalled.

“Important things come to the surface.

“All the little things don’t matter.

“You become more at peace.

“When I was in prison, the only reason I survived really was because God was there with me.

“It sounds a bit pious when you say it like that but I was very conscious of God when I was there, and was sort of strengthened by that, I think.

“I often think that the terrible people who are doing terrible things have probably had terrible things done to them.

“That’s what I felt about the Iranians who were nasty to me.

“I knew that awful things had happened to them and their families.

“A friend once asked me if I wouldn’t find life dull after Jerusalem.

“As you know, I didn’t!”

She died at the age of 97 in 2019.

Portrait of a trouble-shooter

Terry Waite was known to the guards as “the three-metre man” because of his height.

Four years later, he also successfully negotiated with Colonel Gaddafi for the release of the four remaining British hostages held in the Libyan hostage situation.

As an envoy for the Church of England, he travelled to Beirut in January 1987 to try to secure the release of four hostages, including the television journalist John McCarthy who had been kidnapped by jihad terrorists in April 1986.

He was himself kidnapped.

Mr Waite remained in captivity for 1,763 days, much of which was spent in solitary confinement.

He spent those years chained hand and foot, to a wall in an underground cell.

They were suspicious and interrogated him for the first year to see if he was being truthful about his mission.

That interrogation culminated in a mock execution, after which they told him they believed him and would release him within a week.

They had moved him, in a fridge, to the women’s quarters in a private house, and gave him better food to eat than he had had over the previous year, in preparation for his release.

But some political event occurred in the outside world and, to this day, Mr Waite does not know what it was, and his release never happened.

The political change had him back in normal hostage quarters again to spend the next three years in solitary confinement.

“I was determined not to be beaten,” he said.

“Besides which, I was convinced of the rightness of what I had done.

“It was a right and just cause and that kept me going.

“My faith helped me, too, but not in ways that some people might expect.

“I didn’t feel, as some people claim to feel, the close, warm presence of God.

“I often felt very isolated and frightened.

“But I didn’t feel abandoned by God.

“He wasn’t to blame for my situation.

“I don’t blame Him for things that happen in life.

“I feel that is a very childish view.

“It isn’t a just and fair world and I don’t believe suffering is apportioned equally.

“Many suffer more than others.

“But having said all that, I think if you can say, as I could say because of my faith, in the face of my captors: ‘Well, you have the power to break my body, the power to bend my mind, but my soul is not yours to posses’, it’s enough to enable you to maintain hope.

“And if you can maintain hope in situations, you can often deal with them constructively, and that’s what I tried to do.

“I was immobilised, I was chained, I had to live all my life internally.

“But that is not so dissimilar to what some people have to do because of illness or whatever.

“I don’t single myself out as a special case.”

He tried not to think of his wife and family too much, for it was simply too painful to do so.

He worried that his kids would have been affected by his absence, perhaps dropped out of university, and that was a real source of concern to him.

He was finally released on November 18 1991.

Having studied theology, but with no thoughts or desire to seek ordination, Cheshire-born Mr Waite became an education officer with the Church of England.

He became an adviser to the first African Archbishop of Uganda, and was seconded to work in Rome as a liaison officer with the Roman Catholic Church.

The family returned to England so that the children could complete their education at home, and it was then that the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, recruited him as an adviser on international affairs.

It was a baptism of fire for the policeman’s son as he was pitched into the Iranian crisis following the Ayatollah Khomeni’s revolution.

He said: “My style of working has never been to pay money to secure the release of hostages, but to try to find a peaceful and face-saving solution.

“It worked in some situations and not in others.

“We went into Beirut, largely because of pressure from the Episcopal Church in America, who urged us to try to secure the release of Terry Anderson and Tom Sutherland.

“To be honest, originally we didn’t want to get involved for we knew it would last a long time and was highly political and contentious.

“My belief is that once you take up a cause like that, you just stick with it.

“But, after many appeals, by many people, we decided I would take it up.”

Every time he went to discuss the potential release of a hostage, he swapped his usual battery-powered watch for a wind-up one.

His theory was that if he were captured, chances were the battery would go flat before he was released.

As it turned out, he had the wind-up watch with him when the Hezbollah pounced in 1987, but it did him no good whatsoever as they took it from him before throwing him into the cell that was to be his home for five years.

“I calculated there was an 80% chance I would be captured or killed,” he said.

“But the reason I went back was simple.

“I felt the Church had to be the last body to walk away.

“If these hostages could not rely on the Church to try to help them, then who could they turn to, and what did that say about the Church?

“There comes a point in life where political decisions and moral decisions have to separate and this was one of them.

“Politically, it may have been mad for me to go back, but morally, it was absolutely the right decision.

“I’m no saint, and I definitely haven’t always done the right thing in my life, but that time I’m 100% sure I did.”

Despite his ordeal, Mr Waite refused to blame his captors, believing that they were just “ordinary lads from the villages, brought in to do a job”.

Mr Waite said: “I hope, if I had to, I would have the courage to do again what I did.

“It was my decision, not Robert Runcie’s, that I went.

“If the Church commits itself to people, it should not forsake them until the involvement becomes dangerous for the people themselves.

“I don’t remember lots about my lectures when I was a student, but one thing I do remember one of our teachers saying was this: ‘If ever you stand on a public platform, or in a pulpit, always remember that one day you may be called down from that pulpit and asked to put into practice that which you have spoken about’.

“I haven’t always done that. Of course, I haven’t.

“But at some point in life, you have to take a stand and I feel that is what I did in Beirut.”