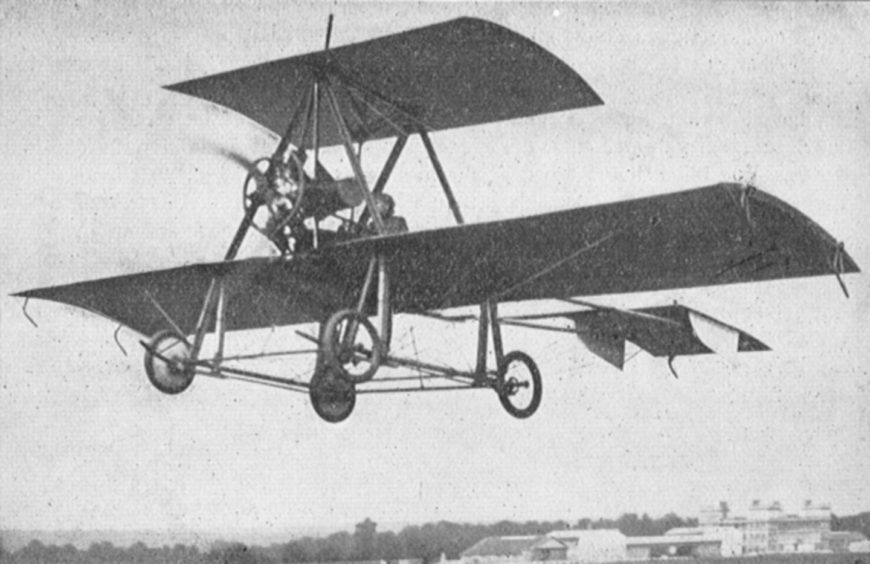

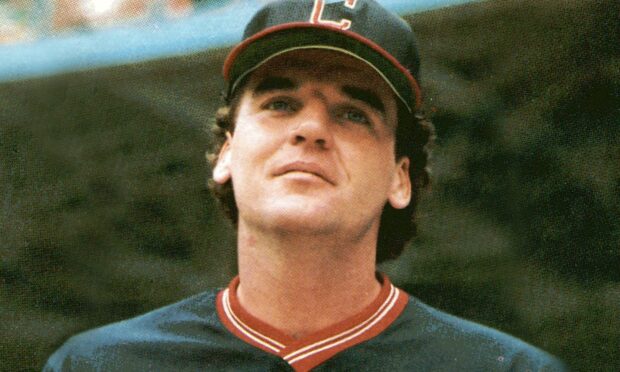

It was the day Dundee aviation pioneer Preston Watson made the supreme sacrifice.

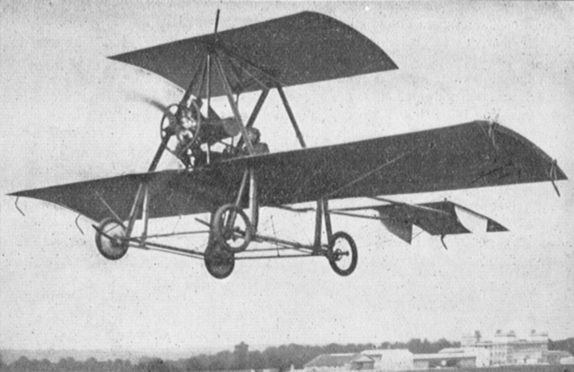

Watson was flying a biplane in East Sussex 105 years ago when it crashed to the ground just three months after obtaining his pilot’s licence.

Loud bang

At the age of just 34 he was one of the oldest and most experienced pilots in the Royal Naval Air Service when “a loud bang was heard and the machine was seen to fall through the clouds”.

Two men who witnessed the accident rushed to the spot and found Watson dead.

The machine was wrecked with parts of it in an adjoining field.

People living near the scene of the accident stated that they heard the aeroplane engine but could not see the machine.

There was a report that the biplane appeared below the clouds and fell to earth with a crash.

It was thought that the explosion must have happened above the clouds.

Eyewitnesses said the biplane “dropped like a stone” into a field opposite the Cross-in-Hand Hotel.

One man said the machine seemed to be planing down when there were three successive bangs and it fell nose first.

After it struck the ground there were splinters which flew into the air to a height of about 50 feet.

Watson’s body was buried beneath the debris of the shattered biplane.

His head and shoulders were only visible from between the engine and the propeller.

A doctor was called but could do nothing and the body was removed before the wreckage was immediately taken charge of by the military authorities and the field guarded.

Mechanical failure

The Caudron G3 he was killed in had only been in operation for a year.

The cause of the crash appeared to be structural or mechanical failure and not negligence or ignorance.

Local historian Dr Norman Watson said: “Although Preston Watson was a brave and resourceful pioneer airman, I think local historians have borrowed a little ‘latitude’ over the likelihood of him beating the Wright brothers to powered flight.

“The accounts which place Watson ahead of the pioneering Wright brothers, and the plaque at Dundee Airport which publicly advances the story, lack contemporary evidence and are based on one man’s memory stretching back 40 years from 1953.

“Powered flight was not an option for a provincial Scottish engineer in December 1903 when Orville and Wilbur Wright began our aviation adventure.

“There was not an engine in Europe capable of such a thing.

“It is a claim Watson never made of himself, and it was not mentioned in any of Dundee’s newspapers in 1903.

“Though I admire him hugely for his contribution – I doubt if Watson achieved powered flight in 1904, 1905 or 1906.

“Instead, it is worth acknowledging Preston Watson as a skilled aviator who contributed to the development of powered flight, and who made the supreme sacrifice when he was killed during the war near Eastbourne while flying a biplane, three months after obtaining his pilot’s certificate.”

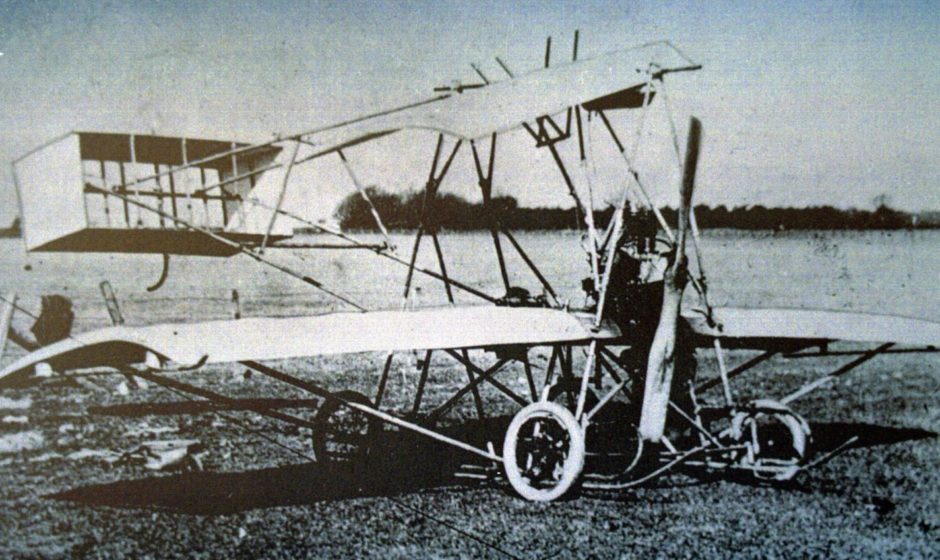

The claims were backed only by circumstantial and anecdotal evidence including that of Watson’s older brother James Y Watson that Watson’s first machine was actually a powered aeroplane.

Dr Watson said the earliest reference to him flying that he could find was a flight at Forgandenny in October 1909.

Brave and brilliant

He said the extensive obituaries carried in the Advertiser and Courier in 1915 also made no mention whatsoever of a 1903 flight.

“Moreover, I have a fundraising letter at home from the newly-formed Dundee Aero Club, dated December 1910, saying that they had just received a donation of their first-ever aeroplane (courtesy of Watson) which was ‘a semi-biplane type minus an engine’.

“Incidentally, the club had 30 members in 1910, including DC Thomson.

“It is a shame from Dundee’s point of view, but it certainly seems that Watson developed his first powered aeroplane in 1908 and tested it in 1909.

“And it was that year that he patented his first plane.

“This is not to lessen his considerable achievements as a brave and brilliant aviation pioneer.”

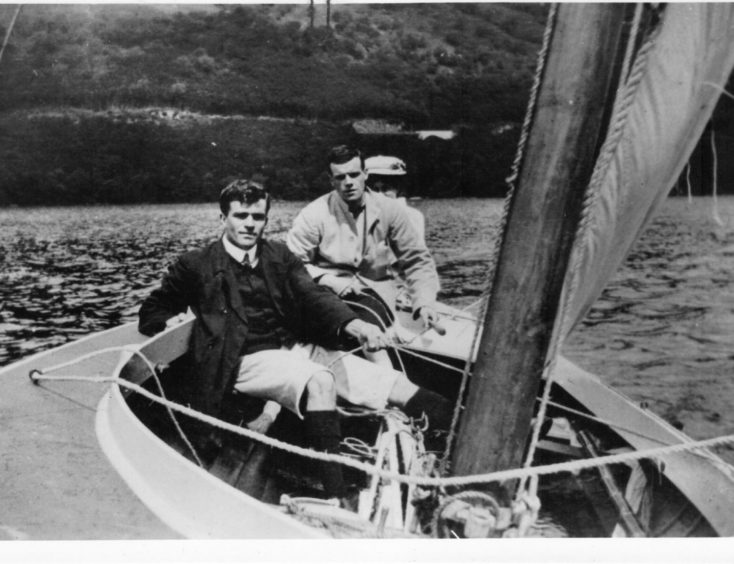

Born in 1880, Watson was born into relative prosperity.

He was the son of Thomas Watson of Balgowan, of the firm Watson & Philip.

Watson went to Dundee High School where he was an all-round sportsman before studying physics at Queens College in Dundee.

He was interested in all things aeronautical from an early age and constructed model gliders and even experimented on captured birds.

One day he was sitting on the wall of the Dundee Esplanade, close to the railway bridge, while his Newport Rugby Club team were busy training.

A friend asked why he was just sitting there instead of training with the others and Watson told him: “Some day we are going to fly, just like these gulls.”

Watson entered his father’s business, in time becoming a partner, but most of his energies were turned towards the study of aviation science and aircraft construction.

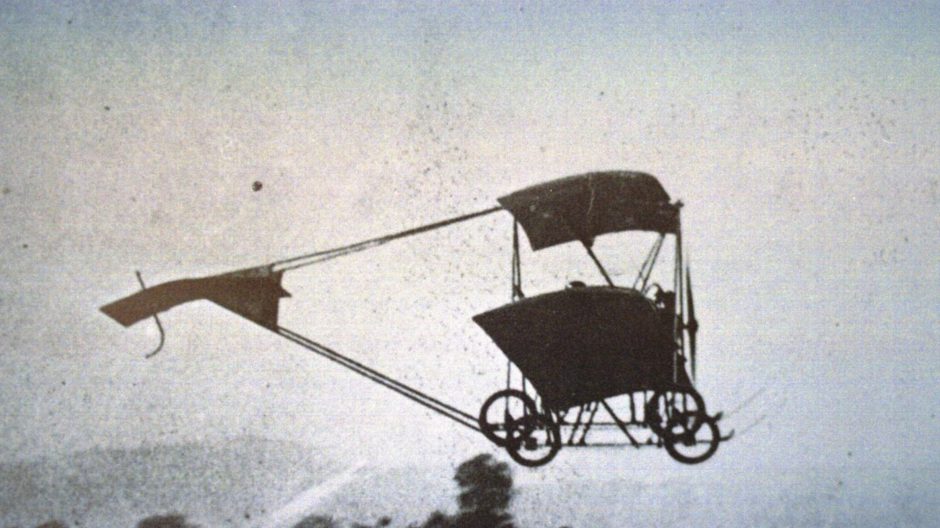

Rocking wing system

He was obsessed with the idea of building a flying machine and persuaded his father to advance him £1,000 to do just that.

He also invented a rocking wing system for control which he patented in 1909.

At the same time, he devised a control system using a single ‘stick’ control for up-down and turn-and-bank, which remains fundamentally the system in use today.

It is very likely that he was the first to do so.

He built and adapted three planes before he volunteered for active service in the air when war broke out.

He underwent training at Hendon in the spring of 1915.

Watson obtained his pilot’s certificate and became a sub-lieutenant in the navy wing of the Royal Flying Corps, later the Royal Naval Air Service.

He wrote to his wife in February that year about his commission being “in some sort of connection with the experimental work at the aircraft factory”.

It was only after his death that the real campaigning to get Watson into the history books began, and his biggest supporter was his brother James.

James introduced himself “as the first man to fly a heavier than air machine in Britain” during a touring exhibition by the RAF which reached City Square in Dundee in January 1949.

He said that the plane had been built by his brother, the late Preston Watson, in the same year (1903) as the American Orville Wright made his first flight – but, because James was lighter than his brother, he had made the first flight in it at Errol.

Four years later, during celebrations to mark the golden jubilee of the Wrights’ flight in London, James stated that “his brother Preston Watson made a powered flight of between fifty and a hundred yards in 1903”.

James said: “If I hadn’t tried to establish my brother’s claims I would have felt I was not doing the right thing by him or Scotland.

“Whether Preston’s flight was the summer of 1903 or the summer of 1904, six months after the Wright Brothers, I can’t recall definitely, but I do claim Preston’s machine was far ahead of theirs in design.”

Those who testified included John Christie who had been a ploughman on Daleally farm from 1900 to 1906.

He said he often stopped work to watch the plane clearing hedges and fences and was sure the plane had been flying in 1903.

Blacksmith’s anvil

Broughty Ferry man Alexander Robertson also told how, shortly before he had left school in 1903, aged 13, he had guided a pony to help Preston Watson pull his plane from the shed to the flying field.

David Urquhart of Kirriemuir remembered and described exactly how the plane had been launched, using two falling 56lb weights and a blacksmith’s anvil to catapult it into the air after running along greased wooden rails.

However, none of these witnesses could produce any documentary evidence to back up their claims as to the exact dates involved.

For years, James sought for proof of the date of his brother’s first powered flight.

The whole thing hinged on the date that Watson bought his first engine.

In 1955 a letter sent to James from John Bell Milne from Dundee, who was a good friend of Watson, appeared to put the matter to rest, once and for all.

He said: “There was a good deal of secrecy about the building of this first aeroplane.

“I was among the first to see the machine in its early stages of construction at the works of his cousin at Carolina Port.

“The framework was that of a glider.

“There was no wheels and no engine.

“In 1906 Preston learned that it was possible to purchase a 60lb 10/14 hp Dutheil-Chalmers engine from Santos-Dumont in Paris.

“I quite remember he asked me to accompany him on his mission. It was, however, too close to my examinations in Edinburgh to allow me to go.

“I have still a wonderful memory; 1906 was bound to be the year.”

Aeronautical historian Charles Gibbs-Smith later carried out detailed research into the Scottish claims for a book on aircraft development in 1960.

In 1966, Gibbs-Smith wrote to The Courier repeating his views: “There is no truth in the story of the 1903 flight, and after confronting Mr James Watson with the facts of the case, he wrote to me in 1955 saying, ‘I make no claim that the machine that Preston used in 1903 was a powered machine’.”

Indeed, a year before his death Watson was quoted in an aviation magazine as saying: “These gentlemen, the Wrights, were the first to fly in a practical way.”

Watson is buried in Dundee’s Western Cemetery.