For more than a millennium, Dunnottar Castle has seen countless attempts to storm its ancient walls and break down the doors of this glorious, ancient stronghold.

The latest attempt – a tawdry bid to break through a door and lock at the front of the imposing edifice last week – is not even a footnote in a history which has seen the castle attacked by Vikings, stormed by William Wallace and bombarded by Oliver Cromwell’s cannons as he tried to seize the Honours of Scotland, the nation’s crown jewels.

The fortress, sitting high on the cliffs of a rocky outcrop jutting into the sea just south of Stonehaven, was even the scene of a Dark Age siege described as the first major battle between Scotland and England.

Now, the fascinating story of Dunnottar Castle – graced by Kings and Queens of Scotland – is set to be retold, with bold plans to put a human face on the history of the people who lived, worked, defended and suffered there over the ages.

“I think the history of Dunnottar Castle encompasses what Scotland was about,” said Jim Wands, the castle custodian.

“The history of the castle is the history of Scotland in miniature – invaded, retaken, and protecting important things for the country.

Symbol of Scotland’s nationhood

“For example, the Honours of Scotland were a symbol of Scotland’s nationhood.”

Jim said work is now under way to revisit the interpretation of the castle’s story, including information, not just inside the keep, but on the coastal walk to it. There are also proposals for a visitor centre, sitting beside the existing lodge house.

The castle’s story is a rich and compelling yarn, stretching back into what is justifiably called the mists of time.

Jim said: “We know the site has been inhabited since Pictish times. There have been people living in the area for thousands of years. In the fifth century, St Ninian brought Christianity here and chose Dunnottar as a site for one of his chain of churches that ran right up the coast of Scotland.”

Dunnottar’s earliest mention in history comes in the Annals of Ulster of 681AD when a siege at the fortress is referred to, involving King Bridei, who was trying to unite the Picts to stand against the overlordship of the Angles.

Some 300 years later, in 934, the castle was again under siege – this time at a pivotal point in our national history in what could be viewed as the first big battle between the Scots and the English. Constantine II, King of Alba, survived a month-long siege at Dunnottar against the King of Wessex, Athelstan.

King killed in Viking invasion

Constantine went on to extend his influence across territories driving back Angles and Vikings. It was his campaign which brought much of what we know as modern-day Scotland under the direct rule of a King of Alba. And so Scotland was born.

Sieges and battles were Dunnottar Castle’s stock in trade over its long history.

“We know that during the ninth century, King Donald II of Scotland was killed defending Dunnottar Castle from a Viking invasion,” said Jim.

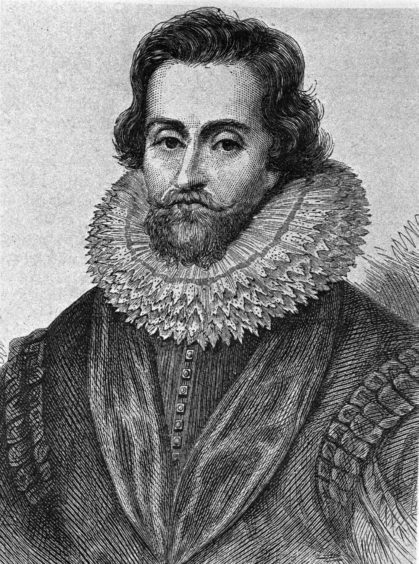

During the Wars of Independence, the fortress was garrisoned by Edward I, Hammer of the Scots.

It was taken back in dramatic fashion by William Wallace in 1297, who laid siege then stormed the castle, burning down the chapel with the English troops inside. Legend had it that Wallace scaled the cliffs to the south of the castle and gained entry through an unguarded window.

In the following centuries, Dunnottar Castle became the seat of the great Earls Marischal of Scotland, and was extended and improved – although not without consequence.

Jim said: “Sir William Keith, the Great Marischal of Scotland, built the Tower House at the castle in 1392, but because he had built it on what was consecrated ground, the Pope at the time ex-communicated him, which was a devastating blow for someone of his standing. So to make amends he built Dunnottar Church and paid some money to the church, so the Pope let him back into the church.”

James VI was living it up

The castle saw royal visitors, including Mary Queen of Scots on two occasions with her son James, the future James VI of Scotland and First of England.

“James came back in 1580 and spent 10 days here stag hunting and basically living it up,” said Jim, who has been castle custodian for six years.

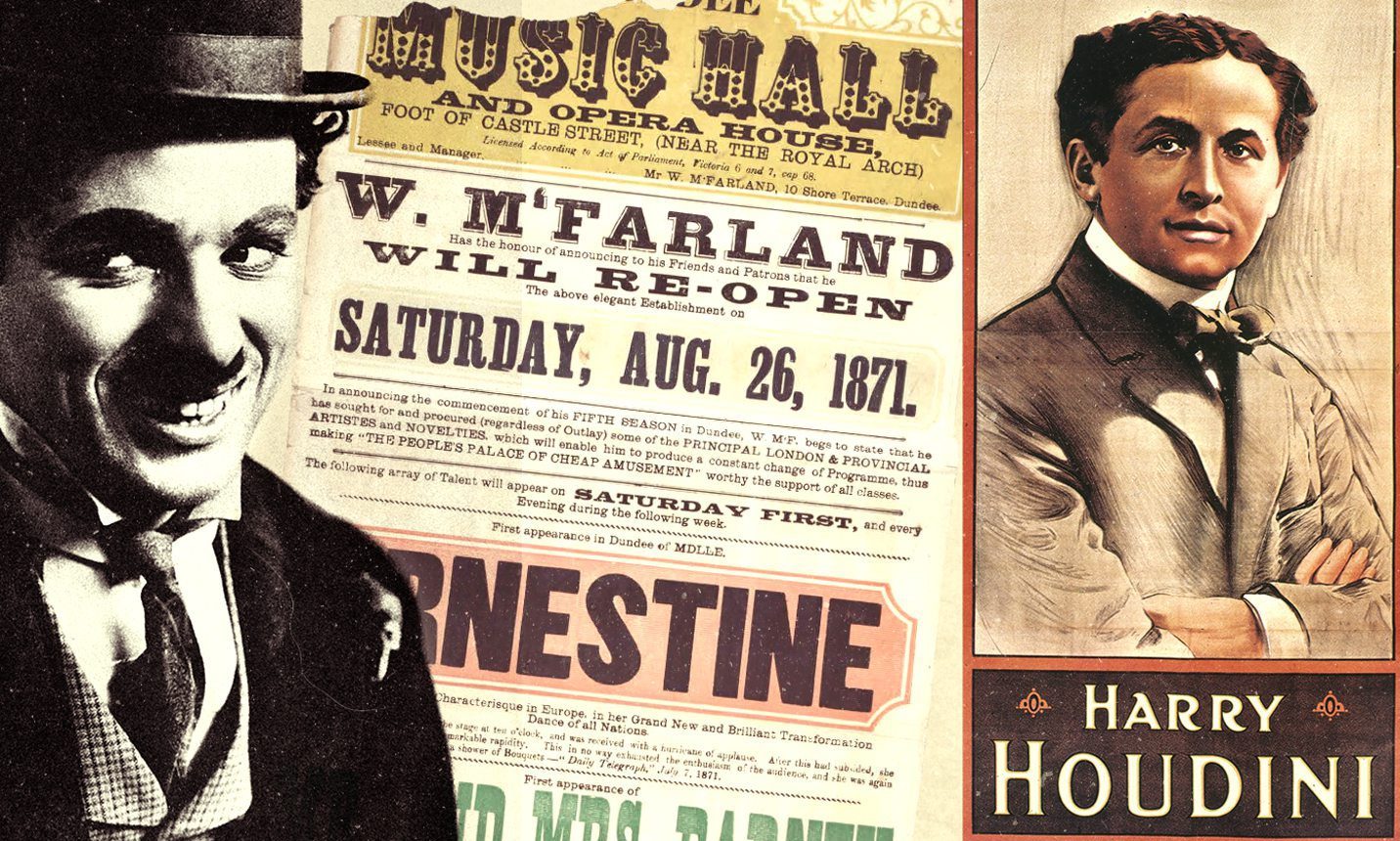

He reckons one of Dunnottar’s finest moments came in 1651 in saving the Honours of Scotland, despite Oliver Cromwell laying siege for eight, long months. The Roundhead leader wanted to claim the Scottish crown jewels, which had been hurried up the coast from Edinburgh for protection as Cromwell’s troops advanced.

But in the midst of the siege, the Honours were smuggled out and hidden in nearby Kinneff Church. There are two accounts of how this sleight-of-hand was pulled off from a castle ringed by troops and cannons.

In one, Christian Grainger, wife of the Kinneff minister, asked leave to visit her friend Lady Barras, besieged in the castle with her husband, and was allowed entry. The Honours were hidden in a bundle of flax being carried by a female attendant who was with her and spirited away after they left.

In another version, the honours were lowered down the cliffs in a creel to Mrs Grainger’s maid who was pretending to gather seaweed by the shore, then sneaked them away under the noses of the English troops, the sacred objects covered in dulse for disguise.

Dark days of ‘killing times’

Jim said: “I would love to believe the idea of Mrs Grainger hiding them and walking past the lines of soldiers besieging the castle, but I think the more realistic one was the Honours being lowered over the edge to someone below.”

The siege had seen Cromwell’s cannons battering the castle from Black Hill, where the town’s War Memorial now stands. Eventually, the attackers brought up even bigger guns to finish the job.

“They just bombarded the castle, badly damaging it, and that was pretty much what prompted the surrender,” said Jim.

“The crown jewels were gone by then, so there was no need to tough it out.

“But when they got access to the castle and found the crown jewels were gone, the troops did even more damage to the castle.

“That’s been pretty much a running theme throughout the castle’s history. When people took it over and it changed hands between the Scots and the English, as the English troops would leave, they would damage it so it would be more difficult to defend.”

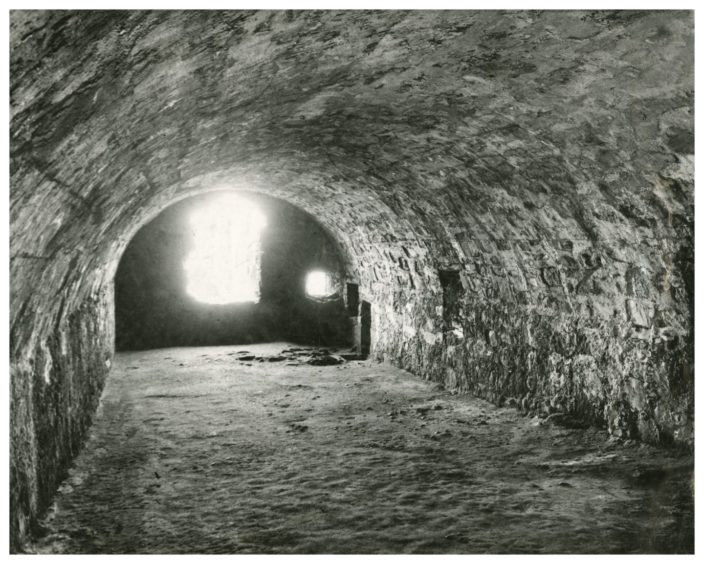

The darkest days of the castle came in the “Killing Times” of the Covenanters in 1685. A total of 167 people – 122 men and 45 women – were imprisoned in one cramped cellar. They were supporters of the National Covenant demanding the Kirk be free of interference from Charles II and his bishops.

Conditions in what became known as the Whigs Vault were horrific.

Jim said: “The prisoners had been marched from the Central Belt up to the castle because the prisons down there were getting full. They were held for eight or nine weeks and their only crime was refusing to recognise the King’s supremacy in spiritual matters.

“They were imprisoned with little food and no sanitation from May 24 to the end of July. We know that 37 Whigs took the oath of allegiance and were released. Another 25 escaped but 15 were recaptured and two fell to their deaths during the escape attempts. Another five prisoners died and the remainder were deported to the West Indies, but it’s believed 70 died of fever on the journey or shortly after.”

Unroofed and stripped of its contents

Barely 30 years later, the glory days of Dunnottar Castle ended. For supporting the Jacobite rising of 1715, the 10th and last Earl Marischal, George Keith, was convicted of treason, his estates forfeited and Dunnottar was unroofed, its contents stripped, to become the ruin it is today.

More than 200 years later, in 1925, the property was bought by the Pearson family and the 1st Vicountess Lady Cowdray began restorations which would see it open to the public again.

“She wanted to make sure it wasn’t getting any worse,” said Jim. “People were coming and taking stones from the castle down to Stonehaven to use in buildings there. If you look up when you are outside the Marine Hotel at the harbour, you will see there are some gargoyles set in the wall. Those are from the castle.”

Today it is one of Scotland’s most famous and most photographed castles and has also been used as a film location for movies as diverse as Mel Gibson’s Hamlet and Frankenstein, starring Daniel Radcliffe. It inspired Princess Merida’s castle in the Disney Pixar film, Brave.

It is now a major tourism draw for the north-east of Scotland and still attracts high profile visitors. Prince Charles and Camilla toured the castle in 2019.

Jim said: “In the last year before coronavirus, 130,000 people came into the castle. But we had a survey on visitors a couple of years ago that found about three times the number who come into the castle, just come and look at it. So when it comes to bringing people into the area you are talking about 300,000 to 400,000 people.”

New ways to tell story

Today, coronavirus has seen the castle close its doors again, but the time is not being wasted. Jim is now at work finding new ways to tell Dunnottar Castle’s story as part of a long-term project, which will include a new visitor centre.

“We are trying to update the experience of going to the castle, by making it more personal. For example, one of the things we are looking at is following the life of one of the Whigs between being released and going to the West Indies. What happened to them, what was their story, what was it like when they were in the castle?

“We want people to feel things rather just look at some signs.

“We want them to know what it would have felt like to live in the castle, what people got up to, the struggles they had, the way they lived. It might be about the baker of that day, what people were cooking, and how difficult it was to get food in and out of the castle.”

Jim added the castle is working on a new website and are also looking at telling people about the castle even before they set foot inside.

“There will be information on the way down to the castle and possibly even further along the pathway towards Stonehaven. It’s just to let you know what you are seeing and give you a better experience of coming to visit.”