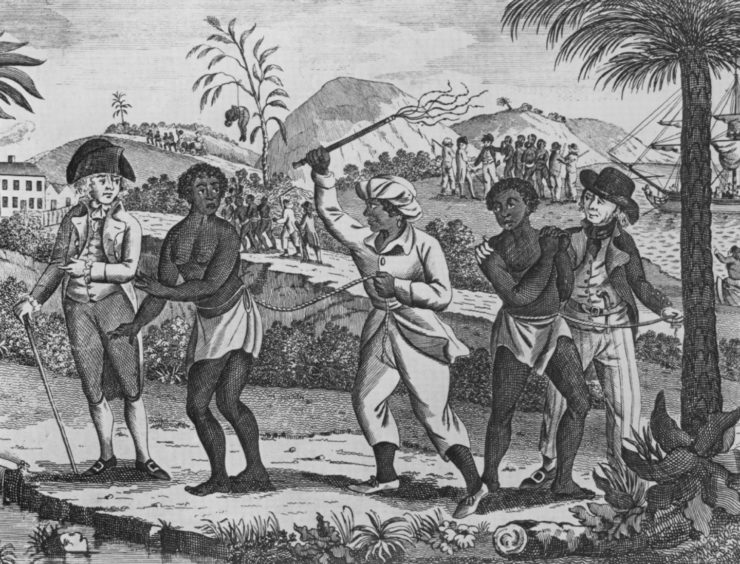

Andrew Watson emerged from the shackled legacy of Scotland’s murky ties to the slave trade to become a trailblazer for black footballers.

Watson was the world’s first black international footballer, the world’s first black international captain and the world’s first black club secretary.

He played for and captained Scotland in two games that would change the course of English football in the 1880s.

Up until the time of Pele, Andrew Watson was perhaps the most important black player in the world, capable of playing on either side of defence or in midfield.

Football was a game for everyone

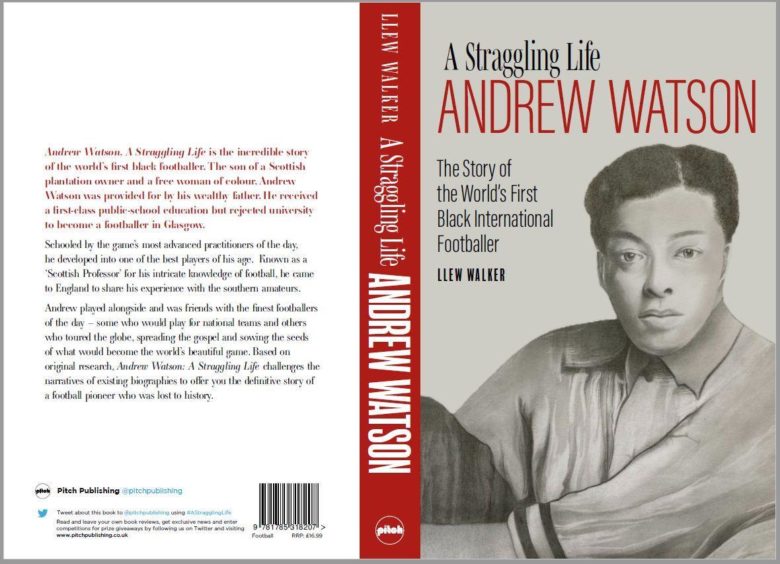

Llew Walker has written a book about Watson’s life and believes the incredible story of the football pioneer should be taught in schools.

Watson died 100 years ago and is buried in Richmond cemetery and Mr Walker is working with a group of enthusiasts to restore his grave to its former glory.

“His importance is immeasurable,” he said.

“Over the last 100 years, the history of the game has often been misrepresented.

“Some still peddle the belief that the history of football is a white, English game.

“Watson’s story, as a black Scotsman, shows that from the very beginning, football was a game for everyone.”

Watson was born in Georgetown, Demerara, the capital of British Guyana to wealthy solicitor and sugar plantation owner, Peter Miller Watson, and a local black Guyanese woman called Hannah Rose.

Watson’s father, who grew up in Orkney, was part of what became one of the biggest West Indian merchant houses – based on slavery, sugar and shipping.

At the age of five or six, Watson, along with his sister Annetta, accompanied their father on a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean for a new life in Britain, leaving their mother behind in Guyana.

His father died when Watson was just 13.

Watson was looked after financially and provided with an annuity of £6,000 which helped pay his school fees, but he did not inherit his father’s wealth.

Watson started his football career with Govan-based Maxwell FC.

Reports at the time suggested he was heavily influenced by the rugby he played at school, and during a game, bent down to pick the ball up and run with it.

He was playing for Maxwell before he enrolled at the University of Glasgow to study engineering, natural philosophy and mathematics.

Watson only attended for about four weeks before dropping out to play football.

In August 1875, Maxwell merged with Parkgrove FC, and Watson became the new club’s vice-president.

For the next four years, he would play around 100 games for Parkgrove.

He invested his own money in the club that rose from a junior park team to challenging for honours against Queen’s Park, Rangers, and many top teams in Glasgow.

Stepping stone to international recognition

During his time at Parkgrove, Watson’s ability as a footballer rapidly improved until, by 1880, he was selected to represent Glasgow in the annual inter-city game against Sheffield.

This was a stepping stone to the national team.

But just as he received this recognition, the Parkgrove club suffered financial problems and collapsed.

For a time, Watson was without a regular club, appearing for the Glasgow Pilgrims, comprised of ex-Parkgrove players.

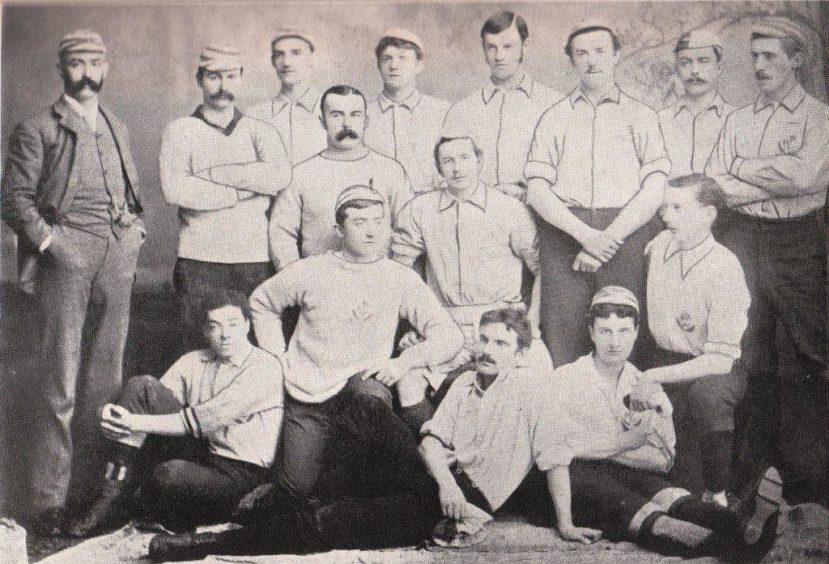

In April 1880, Watson joined Queen’s Park and would play over 110 games, winning three Scottish Cups and four Glasgow Charity Cups.

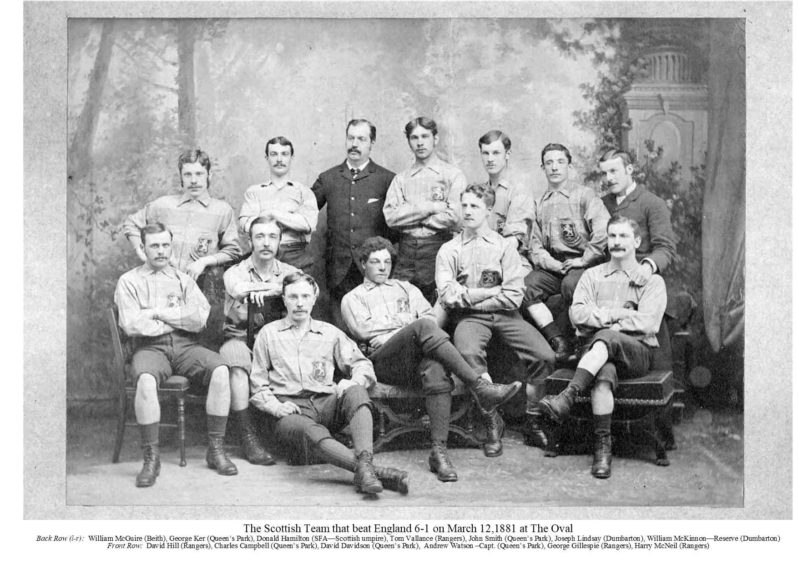

Mr Walker said: “In 1881 he was selected to play for Scotland and captained the national team in one of two of the most significant games in the evolution of football.

“The English’s shocking humiliation on home soil by six goals to one sent shockwaves through the English FA.

“When they received another thumping at Hampden the following year, they were desperate to find a way of improving English fortunes.

“Ever since the first England versus Scotland game, the majority of the Scottish team had comprised of Queen’s Park players and once the whole Scottish team contained players from that club.

“They decided to create an English team in the Queen’s Park mould, who could supply the national team with players who regularly played together and were familiar with each other’s game.

“This team would become known as the Corinthian Football Club, which would play an influential role in the growth of football and its popularity both in Britain and around the world.

“It would influence the creation of many clubs and football associations in many countries, perhaps most famously inspiring the foundation of two-time World Club Champions Corinthian Paulista, who were formed after a visit by the Corinthians to Brazil in 1910.”

Triumph and tragedy

Watson won a total of three international caps for Scotland, which would have been more had he not moved back to London in 1882 at a time when only home-based Scots were selected for the national side.

Tragedy struck Watson in the autumn of 1882 when his wife Jessie, who he married in 1877, died.

Their two children were sent back to Glasgow to live with their grandparents, leaving Watson to combine an engineering career with playing football at a high level.

Watson played for a number of clubs, including Pilgrims and the Swifts, playing in the FA Cup eleven times for the latter.

He was the first black footballer to play in the FA Cup.

In 1883 he was invited to play for the Corinthians.

Watson would captain the Corinthians to famous wins over Sheffield, Preston North End and the FA Cup Winners Blackburn Rovers by eight goals to one.

He remained in London for three seasons sharing his football knowledge with the English amateurs, helping change the English game forever.

He was also selected to represent Surrey County, West Surrey, London, and The South, before returning to Glasgow and joining Queen’s Park again.

In 1886 he retired but was tempted back to football by Bootle FC in Liverpool, where he would live for the next 25 years.

He retired again in 1888, joining the Merchant Marine and heading off to seas for the next 10 years.

He retired to Kew in Surrey around the beginning of the First World War and died there on March 8 1921.

A figure of international importance

Highlands-based historian David Alston said Watson emerges out of Scotland’s extensive involvement in slavery as a black Scot who should be much better known.

He said: “He is clearly a figure of international importance in the history of football.

“His father Peter Miller Watson was born in 1805 at the manse of Kiltearn in Ross-shire, where his grandfather Rev Harry Robertson was the minister.

“Peter was brought up in Orkney but when he was only three and a half his father, James Watson, died – leaving his wife, Christy Robertson, with four young sons.

“And she was pregnant with their fifth son.

“Peter and his brothers returned with her to Kiltearn and he remained there for some years, even after she remarried and moved to Liverpool.

“Peter’s life was shaped by the Robertson family’s involvement with slavery and the plantations of Guyana on the north coast of South America.

“His uncle, George Robertson, had been one of the founders of a partnership which, from modest beginnings, grew to become one of the largest merchant houses trading in the British West Indies.

“Their wealth was based on slavery, sugar and shipping.

“By the time Peter was growing up, a second generation was going out to Guyana, including four of his mother’s brothers and some of her cousins.

“In the 1820s Peter and three of his brothers followed.

“By the 1840s Peter was the principal clerk in Georgetown, Guyana, for the partnership, now known as Sandbach Tinné.

“It was here his two children, Annetta and Andrew, were born to a woman called Anna or Hannah Rose.

“We should celebrate Andrew’s achievements and remember just how much our history is entangled with Africa and the Caribbean.”

The north-east’s slave trade links and how Fettercairn was at the heart of a slavery ’empire’