Janet Rogers was discovered lying in a pool of blood after being struck multiple times by an axe in the kitchen of a Perthshire farmhouse.

Blood spattered the walls and furniture at Mount Stewart Farm near Forgandenny on March 30 1866.

Janet, who was a married mum of five, travelled to the farm of her brother, William Henderson, to help with chores while he looked for a new domestic servant.

Three days later she was dead.

Henderson’s ploughman James Crichton was suspected of the murder but the evidence was only circumstantial.

The trial jury in Perth took just 12 minutes to return a verdict of “not proven”.

The investigation into Janet’s death went cold and it remains one of the UK’s oldest unsolved murders.

We asked criminologist and former police officer Dr William Graham to look at the case reports and he believes something “doesn’t add up”.

What happened on the day in question?

Henderson had breakfast with his sister and left home with a horse and cart at 10.30am to go to the market seven miles away in Perth.

On his return home, between six and seven in the evening, he was surprised to find both the back and front doors of the house locked, and also the shutters of the windows secured.

When his sister didn’t respond to his calls, he scrambled in through an open upstairs window by a ladder and made his way to the kitchen on the ground floor.

In the darkness he could just make out what seemed to be bed clothes lying on the floor.

Janet was lying below the clothes and was stiff and cold.

The body was cut and lying in a pool of blood.

Henderson sought assistance from a doctor and a constable.

He went to the railway station at Bridge of Earn and sent a letter by train to Perth to the assistant procurator fiscal of Perthshire, John Young.

It said: “Dear Sir, Please come out here immediately, as my sister has been murdered whilst I was in Perth. Your obedient servant, William Henderson.”

Policing in the 1800s was very different

Young rounded up a Superintendent McDonald and several constables of the County Police and the investigation started in earnest.

In the 1800s, policing in Perthshire was pretty different to what it is now.

No forensics, only 80 officers, and just two detectives who were already investigating one murder when Mrs Rogers was found dead.

The Courier said a scene of a horrifying description was presented which bore “unmistakeable signs of a desperate struggle having taken place”.

“The murdered woman was lying on her back in a literal pool of blood, with her arms outstretched and her hands covered with gore; the floor was covered with bloody foot marks; the furniture lay about in indescribable confusion; and the walls near the part of the room where the foul deed had evidently been committed were as thickly spotted with blood as though they had been sprinkled with a brush.

“The woman’s head lay within a few feet of the door, and her feet at the fire place.

“The bed clothes had apparently been pulled out of the bed and thrown above her after the murder, as, with the exception of the sheet next to her body, all the other clothes were free from any stains of blood.

“There is nothing whatever to favour the supposition that the deed had been committed in the bed, as not a single spot of blood was to be found about it; while, on the contrary, from the condition of the room, there is every reason to suppose that the woman had been brutally butchered while fulfilling her domestic duties.

“The murder had evidently been committed five or six hours previous to the arrival of the police for the body was found by them to be quite warm, though the extremities were cold.

“No scratch or injury of any part was found upon the body; but the back part of the head, which was covered with two woollen caps, was dreadfully smashed, and a large irregular hole of considerable depth was found beneath the right ear.

“The injuries had evidently been inflicted with the kitchen axe, which was found lying unconcealed near the body covered with gore, and portions of hair were sticking to it.

“Whether the helpless woman had been struck down with the axe it is impossible to say, but there is little doubt, from the examination that was made, that after the woman had fallen or been knocked down, her murderer had struck her on the head with it two or three times – dealing one blow behind the right ear, and one or more on the middle of the back part of the head.

“The house was carefully searched with the view of obtaining a clue to the murderer, but, we understand, without much success.

“That the woman had been murdered by robbers with the view of their more effectually plundering the house did not appear to the police to be the case, as, with the exception of the furniture in the kitchen, everything remained undisturbed and no article seemed to have been taken away.”

Excitement in Bridge of Earn and Perth

Mr Young and Superintendent McDonald placed two or three of the constables around the house to guard it before driving off back to Perth.

The Courier said the case was one of “considerable mystery” which had created “the greatest excitement in Bridge of Earn and in Perth”.

“Henderson denies all knowledge of the affair; but affirms the house had been entered by robbers, who had carried off some money, and who, he supposes in order to effect a perfect exploration of the house, had first murdered his sister.

“From the loneliness of the place, it is perfectly possible such a thing may have occurred without its being detected; but it is rarely if ever the case that any farmhouse is set upon by thieves in the daytime, when the murder must have been committed, and especially when ploughmen were working in the neighbouring fields.

“Besides Mr Henderson’s foreman was working on the farm all day, at a small distance from the house, and until he dropped work – about five or six o’ clock – he heard no unusual noise about the house nor had he seen his master’s sister for a considerable time before that.”

Henderson later said the farmhouse was found to be “wholly ransacked” and the contents of a pocket-book and a £1 note which were in the closet were missing.

He said he did not find anything else was missing until his sister’s funeral when he found a pair of trousers and a cap had been taken along with some eggs.

Newspapers across the UK initially carried descriptions of a “tramp” reportedly seen leaving the scene around the time of the murder and a £100 reward was offered to anyone who could offer information that might lead to a conviction.

The investigation that ensued lasted a year and was plagued by a lack of substantial evidence and unreliable witnesses.

But just before Christmas 1866, the police found a reason to arrest Crichton.

Henderson had fired a servant, Christina Miller, just before the murder, and she had gone to stay with Crichton and his wife.

In a police interview, Miller said that two days after the killing, she overheard Crichton confess and he was arrested.

Crichton was subsequently charged with murder but following a trial at Perth in 1867 the case was found not proven and Crichton was released.

“I was not in the farmhouse of Mount Stewart on said Friday and did not see Mrs Rogers there, or inflict any injury upon her,” he said.

“Neither did I take any money or any article from said house.”

Mental health deteriorated

The murder had a lasting legacy.

Henderson never got over the lack of a conviction.

He strongly believed Crichton was responsible and died in Murray Royal Asylum in Scone in 1890 after his mental health deteriorated.

Crichton relocated to Dunfermline following the murder, with his family, and continued to work as an agricultural labourer.

He died in 1894 at Milton, Markinch, and the official cause of death was gangrene.

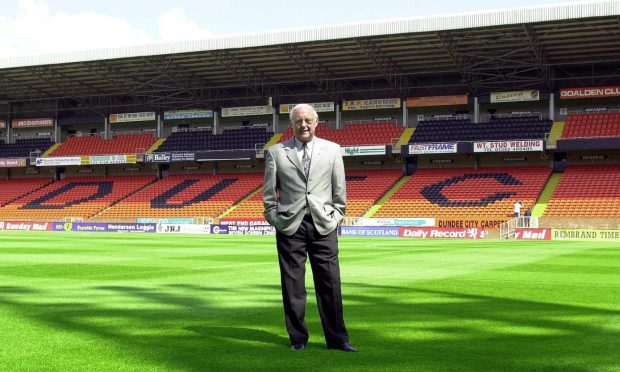

Abertay University criminologist takes another look at the evidence after 155 years

Dr William Graham is a senior lecturer in criminology at Abertay University and a former senior police officer who retired from Strathclyde in 2010 after 30 years’ service.

He said: “This is a cold case that will almost certainly never be closed until there is a prosecution but a few things jumped out when I looked at the evidence in the reports from the crime scene.

“Henderson said he came home to find all the doors locked and the windows shuttered and got in through an upstairs window to find his sister lying on the kitchen floor.

“Burglars and murderers don’t tend to be so careful – first of all, if it was a random burglar who came across the lady and killed her, would he be likely to start covering her up with a blanket and then lock all the doors and windows before leaving?

“How did he get out if everything was locked up? That doesn’t tend to add up in my mind.

“There are very few random killings by strangers – it’s usually someone who is known to the victim in the vast majority of cases.”

Conflicting stories

Dr Graham said it didn’t look like a robbery because police initially found nothing was taken and that the house had not been disturbed although Henderson later claimed the place was “ransacked”.

He said Henderson’s “conflicting stories” would have raised a red flag to police nowadays but acknowledged that policing back then was still in its infancy.

“They didn’t have enough resources and I don’t think they investigated it very well but remember this was only 66 years since the first Scottish police force was formed,” he said.

“Nowadays police would be looking at all the facts, all the forensics and they would be checking out all the alibis, especially those closest to the victim.

“Henderson said he left home at 10.30am and returned at 6pm – it’s not beyond the realms of possibility that he killed Mrs Rogers before going to Perth.

“The body was still warm but it was covered up by a blanket which would retain heat.”

Dr Graham said Crichton being blamed for the murder “seems a bit too easy” and he asked where was the motive for him killing Mrs Rogers?

“It seems a motiveless crime,” he said.

“Could there have been an argument between brother and sister at the breakfast table?

“We can only speculate and will probably never get an answer.”