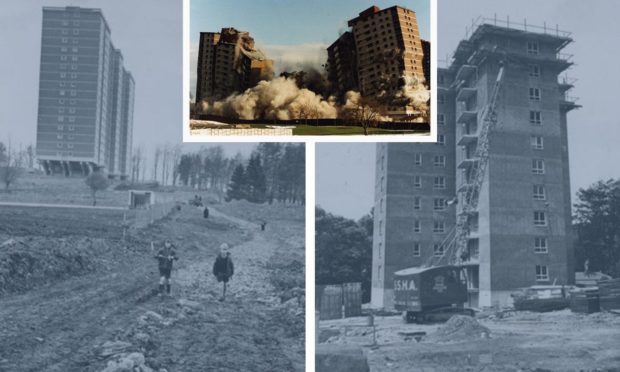

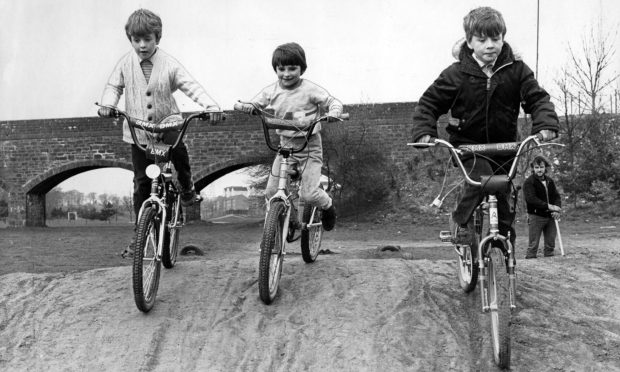

Dundee’s landscape changed dramatically as multis rose and fell between the 1960s and 2000s.

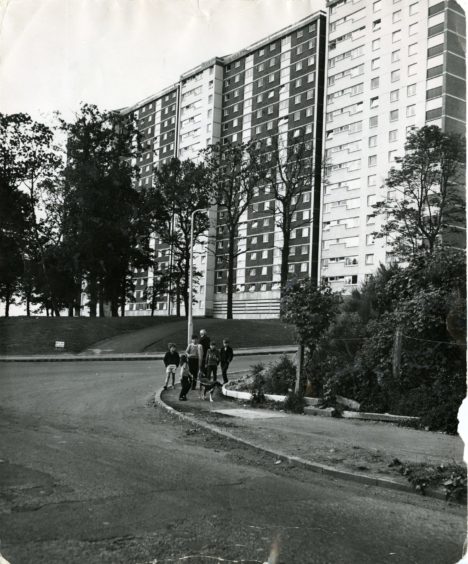

Initially these high-rises were treated with wonder.

There were once 44 multis in Dundee which were a defining characteristic of the city before they became less popular and now only 11 remain.

Dundee’s first skyscraper was built in 1870 and was 102 feet high.

The High Land

The High Land was situated at the junction of Larch Street and Urquhart Street and was erected to house the workers in a jute mill in the vicinity.

It was eight storey’s high in the frontage to Larch Street and nine at the back facing tenements in Walton Street.

The building contained approximately 155 houses and was inhabited by 500 people when it first opened.

The 1871 Improvement Act allowed the Town Council to make sweeping changes to the town, demolishing many older buildings and constructing larger properties on wider streets.

The top three floors of The High Land were closed in 1890 because they were beyond reach of the fire escapes of that day.

The rest of the building was condemned in the 1940s after being considered unfit for human habitation and were finally demolished in the 1960s.

Squalor and disease rightly had no place in Dundee.

The options for councils in the years after the war were limited.

They could improve the existing housing stock — cramped inner-city tenements — offer people the little prefabs or jump aboard the future and build multis.

The proposed use of multi-storey blocks would enable even more dwellings to be packed on to given sites and allow slum-clearance to be accelerated.

Multis started to rise up in the 1960s

The policy was first discussed by the housing committee in 1955 and prototypes were started at Foggyley in 1958.

When the first 15-storey multis were opened in Dryburgh in 1960 the weekly rent was a little over £1.65.

The Dryburgh multis had three flats on each floor with three rooms, kitchenette and bathroom.

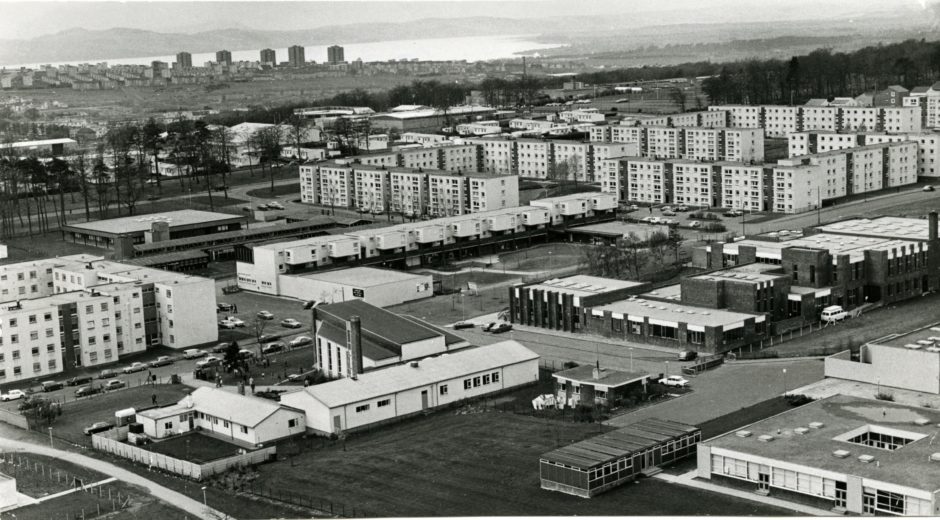

Large numbers of high blocks were built in the 1960s, mostly on the outer edges of the

city but also in a few prominent inner slum-clearance areas.

Ardler Estate was one of the most visually striking of Dundee Corporation’s schemes where six 17-storey slab blocks were the centrepiece.

The multis were built between 1964-1966 comprising 1,788 dwellings and was described as “perhaps Britain’s most uncompromising and monumental example of the ‘Zeilenbau’ pattern of multi-storey blocks in parallel rows”.

The scheme also included architecturally avant-garde groups of single-storeyed ‘patio houses’.

Early multis often had annoying high-frequency vibrations.

During high winds the foot of the Ardler multis were such wind-tunnels that more frail residents wouldn’t even venture out.

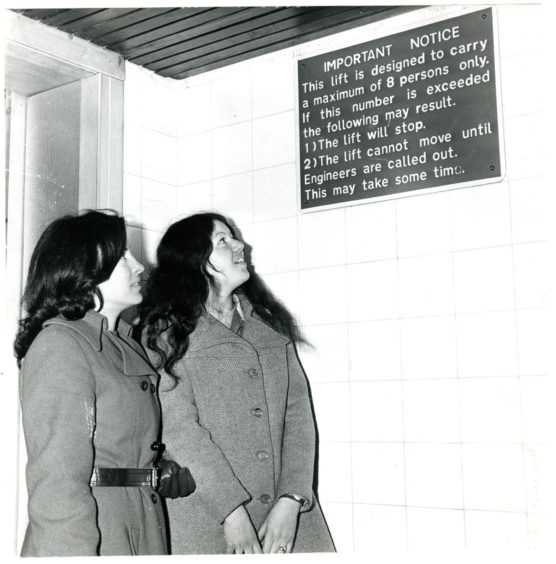

But for many blocks for many years there was no security, which led to all manner of crime and vandalism.

And if the lifts were off — again — those stairs could be a real ordeal.

Less than 30 years since construction began, demolition began on the Ardler multis in 1993 – the first in Dundee to go.

Most of the others followed in 1996, when a crowd of around 15,000 gathered to watch 34,000 tons of concrete being reduced to rubble in just 12 seconds.

The final block, Carnoustie Court, was demolished in 2007.

A golden opportunity in 1968

The four Alexander Street multis in the Hilltown dominated the skyline of Dundee for 43 years.

Carnegie, Jamaica, Maxwelltown and Wellington Courts were seen as a golden opportunity when they were built in 1968 – a chance to escape the decaying tenements and enjoy space, light and comfort.

And plenty of residents had nothing but fondness for their flats, which provided some of the best views possible of Dundee and beyond.

They were demolished in 2011.

Their demolition required just 135kg of explosives to bring down 48,000 tonnes of concrete and steel as hundreds of people turned out on the Law and across the Tay to watch.

Around 600 homes and 50 businesses had to be evacuated and when it was all over the only unwanted damage were a few cracked windows.

Two years later, the looming Derby Street multis fell.

They were twin towers of 22 storeys each.

Butterburn Court was the ‘red multi’ while Bucklemaker Court was the ‘blue multi’.

From an engineering perspective they were arguably one of the most challenging demolitions.

The Derby Street operation was in the hands of Dundee firm Safedem and they dropped Bucklemaker and Butterburn with masterful precision and 10,000 detonators.

A tiny church sat between the two blocks and despite 20,000 of rubbles falling in one fell swoop, it suffered the slightest cosmetic damage.

Multis offered a bright new future

Dundee University opened up its archives, as well as those provided by the council and the central library, for an exhibition looking at the changing face of the city in 2019.

Living Together provided a fascinating insight into the city homes of the past and present from the slums of the Victorian era to council new-builds and multis.

Matthew Jarron from the University of Dundee said: “In the 1960s Dundee looked to the multi-storey tower block to solve its housing needs, and the skyline of Dundee changed dramatically as ever-larger multis were built in the Hilltown, Ardler and other areas.

“Other experiments were attempted, including the hexagonal pre-fab blocks of the Skarne in Whitfield.

“Each offered a bright new future but instead came with inherent social problems and most were later demolished.

“In the 1980s private housing companies such as Hillcrest took over from the council as the main supplier of social housing, and some innovative restoration took place to turn former textile mills into flats.

“It would not be until the 2010s that more council houses were built in the city, but many large-scale private developments have taken place on former farmland on the outskirts of the city – these in turn will bring their own problems in the future.”

Iain Flett from the Friends of Dundee City Archives said the general impression is that multi life was one of community spirit and failed by irregular and poor maintenance.

He said: “Fairly or unfairly, any Scot when asked to think of a rat-ridden slum where children played in muddy pools will immediately think of the Gorbals, and then the wonderful plan to replace them drawn up by the internationally famous Sir Patrick Spence, 2.5 metres long, which can be seen in V&A.

“Work that makes you a household name isn’t always safe from criticism.

“Welcomed by the first residents, the Hutchesontown soon fell out of favour and, sadly, high costs of maintenance and wider social deprivation problems led to their demolition in 1993.

“On the other hand, not only do multi storeys remain popular and functional in Aberdeen but there are moves afoot to give them status as A-listed historical buildings.

“And some multi storey flats in the UK now start at a third of a million pounds.

Flats at the Barbican complex in London, although originally rented to tenants by the City of London at commercial rates, now sell from £325,000 for a studio flat up past £4.5m for four bedroom flats.

“It boils down to economics.

“With property valued at £1,297 per square foot in the Barbican it is going to be economic to maintain lifts and security and communal areas, whereas in Dundee, as in the Gorbals, at property value at a tenth of that, spiralling maintenance costs of lifts and communal areas demand resources that are no longer available to cash strapped local authorities.”