If you were shocked by recent newspaper headlines like “Never Mind Brexit – Who Won Legs-It” and “Your Money or Your Lives”, then imagine how prim and proper Victorian readers must have reacted to seeing prominent public figures openly lampooned and satirised in Blackwood’s Magazine.

They were scandalised and captivated in equal measure, a heady mix that naturally assured the magazine’s future – it became one of the most influential publications of the Victorian era.

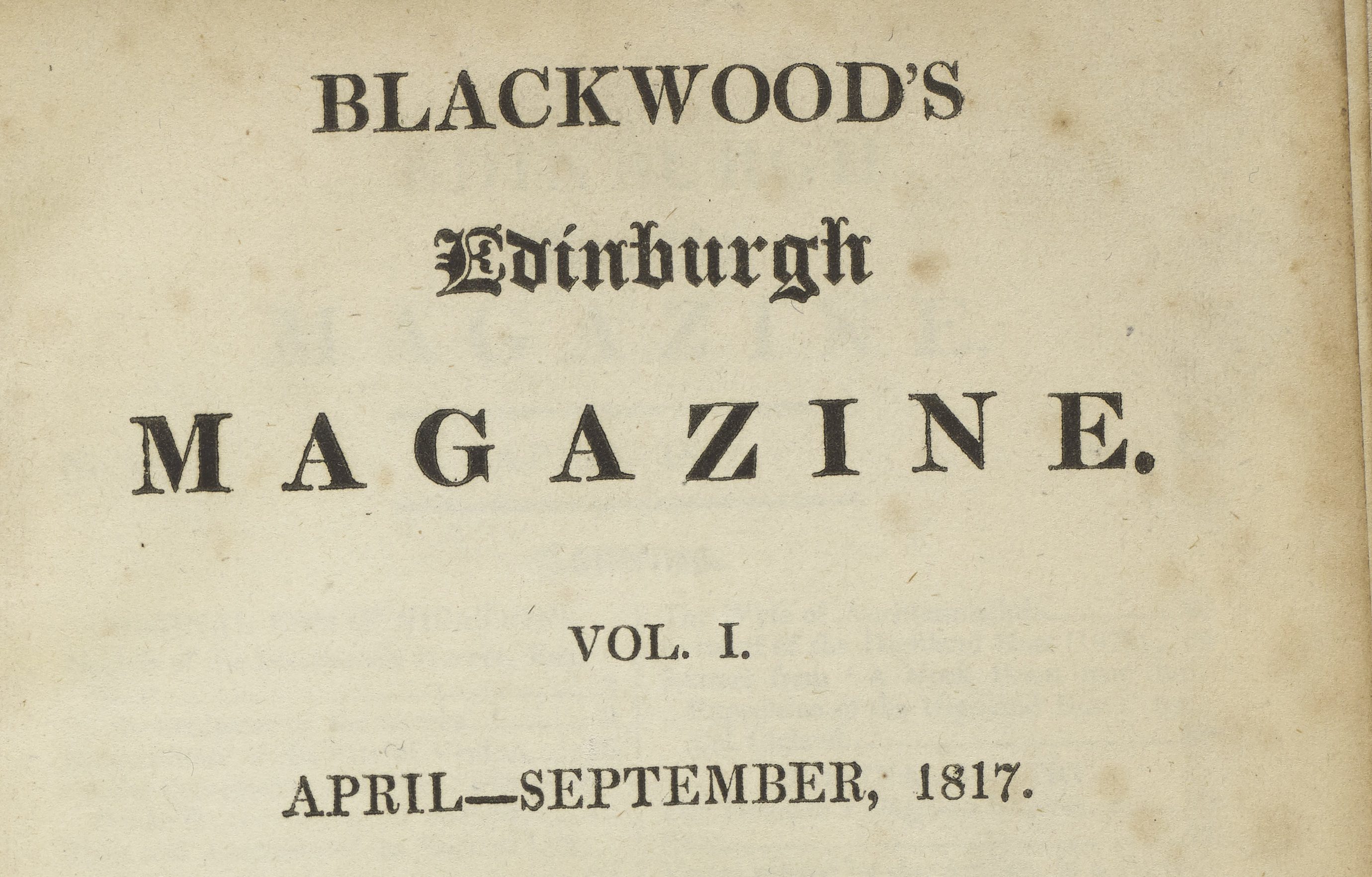

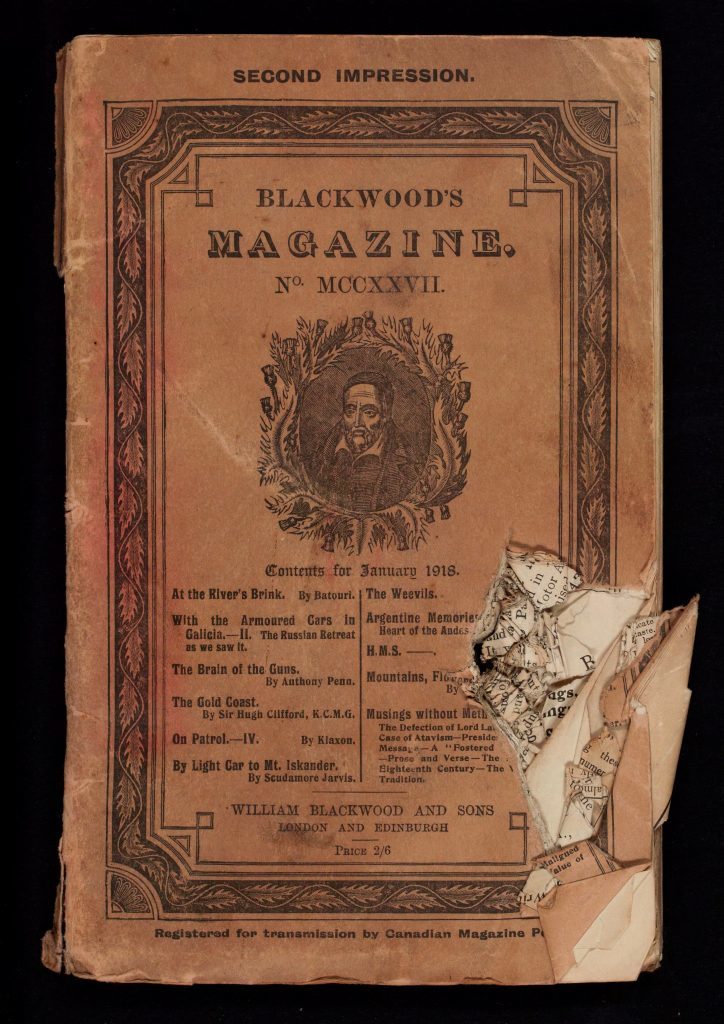

Founded in Edinburgh by publisher William Blackwood, the first edition was published on April 1 1817 and the bicentenary is being celebrated at the National Library of Scotland in a fascinating display called Laws were made to be broken: Blackwood’s Magazine at 200. The exhibition includes a copy of the first ever issue printed on April 1 1817 as well as some unusual items such as a 1918 edition which saved the life of a soldier during the First World War by absorbing the impact of a bullet.

Manuscript curator Dr Ralph McLean put the display together and explains: “It’s a small snapshot of material focusing on four main areas: the early days of Blackwood’s, literary talent, literary successes and failures, and Blackwood’s goes to war.

“One of the problems of putting together the display is that the magazine didn’t really have any illustrations so we’ve used photos, posters and colourful artwork to try to give it a modern context and make it appealing to audiences young and old.”

The very first edition of Blackwood’s, on April 1 1817, crashed and burned, as Ralph explains: “It was designed as a combative Tory counterblast to the existing Whig-supporting Edinburgh Review but its reception was lukewarm, resulting in William Blackwood firing its founding editors and starting afresh.”

Blackwood and his new editors – John Gibson Lockhart and John Wilson – decided to stir things up and court controversy as a sales tactic.

“The rebooted issue which appeared in October that same year was not going to be ignored,” says Ralph.

“Notable public figures, among them the magazine’s original editors, were lampooned in one article about the ancient Chaldee manuscript. This fictitious document professed to be an ancient biblical text that had supposedly just been discovered in Paris but comprised in fact blatant satirical attacks on prominent figures and harsh reviews of certain members of the London literati,” he continues.

It resulted in several lawsuits being brought against the magazine. One quarrel in 1821 regarding an attack on the ‘Cockney school’ of poetry ended in a pistol duel being fought in London which resulted in the death of the editor of the London Magazine, John Scott.

But it wasn’t all scandal and intrigue. “One of the strengths of the magazine was in publishing new fiction,” says Ralph.

“A number of literary classics, including Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, George Eliot’s Middlemarch and John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, made their first appearance serialised in the magazine.”

“In fact the serialisation of Heart of Darkness began in the 1,000 edition of the magazine, and the display includes correspondence from Conrad,” he says.

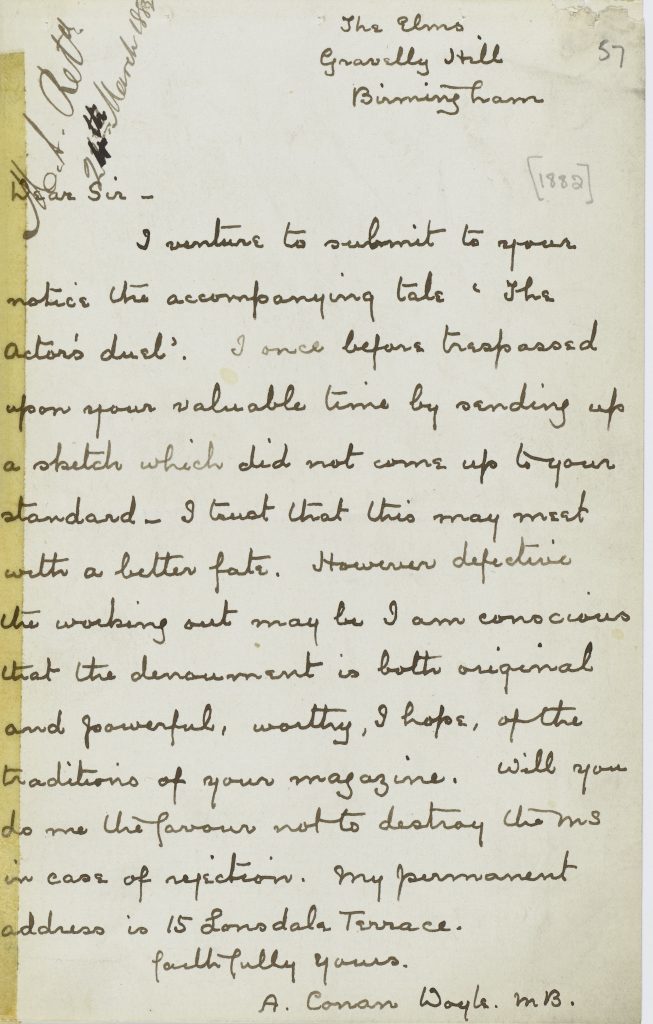

Competition to appear in Blackwood’s was fierce and other great writers including Arthur Conan Doyle and Robert Louis Stevenson were among those who had submissions rejected by the magazine; the exhibition includes a letter from Conan Doyle requesting the return of his manuscript (a short story called The Actor’s Duel) should it not be published.

Although the magazine continued into the 20th Century, its best days were behind it. It lost readers to new journals that made greater use of illustrations and employed fresh attention-grabbing tactics, similar to those that had helped to establish Blackwood’s name. Unable to move with the times, it finally ceased publication in 1980 but was nevertheless one of the longest lasting periodicals of its time.

Despite the Magazine’s penchant for scandal and gossip, Ralph doesn’t believe that it was a forerunner of today’s tabloids. “It was a different format,” he says. “Broadsides, which were around at this point, are closer in type to tabloids, rather than periodicals. However, biting satire never goes out of fashion and these days Private Eye is the nearest thing to a taste of what Blackwood’s offered its readers.

From its humble beginnings in Edinburgh 200 years ago, Blackwood’s has left behind a rich legacy as one of the most original and influential periodicals to have been published in Britain.

“It may have been built on controversy but it came to provide a platform for some of the finest writing in the English language,” Ralph concludes.

Laws were made to be broken: Blackwood’s Magazine at 200 runs until July 2 at the National Library of Scotland, George IV Bridge, Edinburgh. Entry is free.