Passchendaele: ‘the whole of the battle area is a veritable quagmire’.

Dr Derek J. Patrick of Great War Dundee has written the introduction to our 24-page supplement – you can read it below. It looks in depth at the Battle of Passchendaele and other key conflicts on sea and land, and in the air, in 1917.

The Courier Commemorative Souvenir Supplement is out tomorrow.

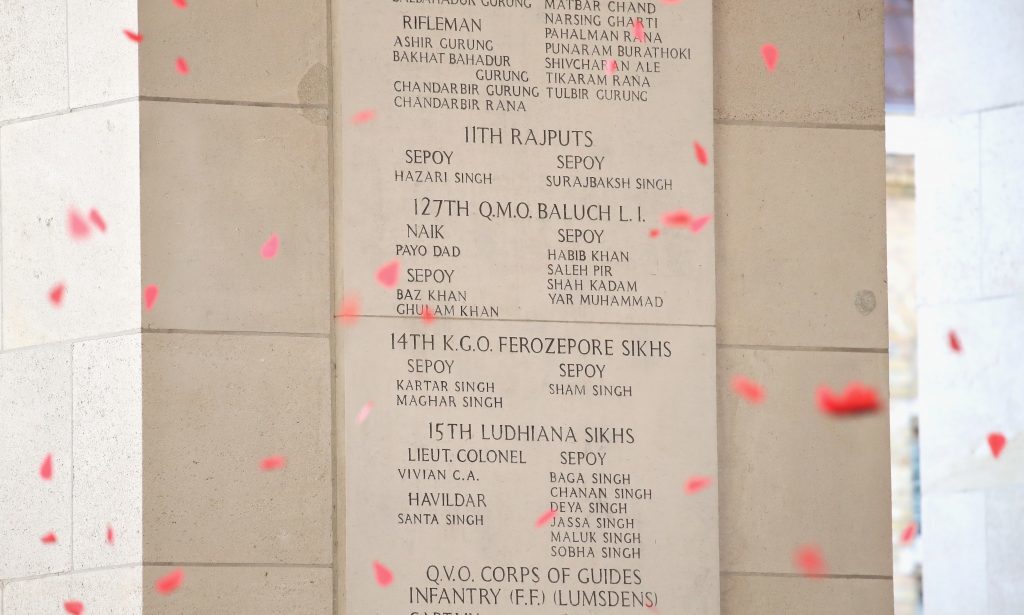

Other subjects, by local experts, include the Zimmermann Telegram, the most significant intelligence triumph during the First World War; the role of Courier Country’s children; the importance of Edwin Scrymgeour’s challenge to Churchill; the unveiling of the Seamen’s Plaque and Rolls of Honour by HRH the Princess Royal in Dundee; and the place of war video games in the 21st Century.

We hope it will provide a poignant tribute to the lives lost and the men, women and children of Courier Country who gave their all to the war effort.

“Passchendaele, or the Third Battle of Ypres, has a prominent place in our country’s shared memory,” says Dr Derek Patrick.

“Like the earlier Battle of the Somme, it has come to shape popular perceptions of the Great War. In little over three months more than 500,000 men were killed and wounded in a series of offensives against the ridges south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres. Third Ypres was conceived as a general advance which would break the German line, and secure the Belgian coast and German submarine bases at Zeebrugge and Ostend.

When the battle ended in November 1917, the British army had advanced only five miles. Heavy rain and constant shelling had turned the battlefield into a quagmire. Siegfried Sassoon’s poem, Memorial Tablet, vividly describes the dreadful conditions in which men struggled and died.

Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in Hell –

(They called it Passchendaele); my wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back, and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duckboards; so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

In his post-war Memoirs Prime Minister David Lloyd George would describe Passchendaele as ‘the campaign of the mud’, a ‘senseless’ offensive ‘that imperilled the chances of final victory’. Much criticism has been directed at the B.E.F.’s Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, who was responsible for orchestrating the offensive.

“Why did he elect to fight in Flanders, and why so late in the year? When the fighting had degenerated into little more than a protracted bloody slogging match why was the campaign not brought to a close?

“From a strategic and tactical standpoint there was an obvious rationale for Third Ypres. General Robert Nivelle’s failure to break German defences along the Chemin des Dames in April 1917, resulted in some 100,000 French casualties, and dealt a crushing blow to national morale. Consequently, a series of mutinies which involved, to different degrees, nearly half the French infantry divisions engaged on the Western Front, had serious repercussions for the Allies.

“The French army was in turmoil and incapable of any new offensive. Elsewhere, Russia was crippled by civil unrest, and while America had formally declared war on Germany on 6 April, it would be some time before her armies could make a significant contribution. The onus was now on Britain to take the initiative and shoulder a heavier burden on the Western Front.

“Flanders was of undoubted strategic importance to Britain which had gone to war in 1914 on the premise of maintaining Belgian neutrality. The B.E.F. had resolutely held the Ypres Salient at huge cost since the early days of the War. Haig’s proposed Flanders offensive not only presented an opportunity to drive the Germans from the high ground around Ypres and perhaps restore movement to the War, it was a chance to guarantee the Belgian coast and reduce the submarine threat to Britain’s shipping. German U-boats were a constant concern when moving men and supplies across the Channel, and in March 1917 had been responsible for sinking almost 600,000 tons of British, Allied and neutral shipping.

“While there was good reason for an offensive in Flanders, its high water table meant that it was less than suitable as a battlefield. Drainage was a constant problem exacerbated by rain and heavy shelling (which destroyed natural water courses), which, in the later stages of the battle, made the movement of soldiers and equipment difficult if not impossible.

“On August 4 1917, one Courier correspondent stated that ‘the whole of the battle area is a veritable quagmire … One shirks from even contemplating what existence is like in the lagoons and brimming rivulets which were once shell craters and trenches’. Ideally, Haig would have attacked earlier in the year before the wet weather had had an opportunity to seriously affect the terrain, exploiting the capture of the Messines Ridge in June 1917 which effectively secured his army’s southern flank. However, logistical problems made this difficult and, in any case, meteorological reports suggested that there was no reason to expect particularly wet weather in August.

“The Third Battle of Ypres began on 31 July 1917 following a preparatory three week long artillery bombardment. Some 150,000 men took part in the assault which enjoyed mixed success. The speed of operations was slowed by rain and mud, and vigorous German counter-attacks which utilised a means of in-depth defence with a strong reserve.

“The adoption of ‘bite and hold’ tactics, concentrating on clear, definitive objectives, saw a more favourable outcome to the Battles of Menin Road, Polygon Wood and Broodseinde, in September and early October, but it was increasingly clear that there would be no significant breakthrough as a result of the offensive.

“On November 6 1917 Canadians finally captured the shattered rain-lashed village of Passchendaele, which had been scheduled for capture within seventy-two hours of the beginning of the Third Battle of Ypres. Field Marshal Haig’s armies had captured the high ground around Ypres but at tremendous cost. Casualties are difficult to state with any accuracy but it seems reasonable to suggest that British and Dominion forces sustained around 250,000 casualties with around 240,000 Germans killed and wounded.

“The outcome of Third Ypres is a matter of considerable controversy. The strategic objectives of the offensive were not realised but both General Ludendorff and Field Marshal von Hindenberg later described the huge impact on the German army, Ludendorff suggesting that German morale never fully recovered. However, while attrition may have deprived Germany of irreplaceable military manpower, and in the short term saw the German army pushed back and shaken, within a few months it had sufficiently recovered to launch the hugely ambitious March 1918 offensive.

“If nothing else, Passchendaele provides evidence of the remarkable courage and endurance of the men who fought beyond all expectation of what anyone could have expected of them. The British army had developed, or was at least developing, an effective system of offensive tactics which integrated aerial reconnaissance, artillery, infantry, and new technologies, with a doctrine of ‘fire and movement’ which, by 1918, would establish their superiority on the battlefield.”

Battle of Passchendaele and other events of 1917: A Courier Commemorative Special Supplement is free with The Courier tomorrow, August 1.