As a major new exhibition tells the story of Scotland from Culloden to the death of Queen Victoria, Caroline Lindsay discovers some of our country’s wild and majestic history.

A beautiful silver plaid brooch, set with an amber Cairngorm stone and surrounded by a ring of 16 red gems, tells a story that ripples across the centuries. As it glitters in a glass cabinet at Edinburgh’s National Museum of Scotland in 2019, it was once worn by the rugged chiefs of Clanranald in the mid-19th Century.

The brooch is just one of more than 300 objects in a new exhibition telling the fascinating story of how Scotland became synonymous with wilderness, heroism and history.

Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland, which runs until November 10, spans the period from the final defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 to the death of Queen Victoria in 1901.

In a nutshell, it tells the tale of how highland imagery – tartan, bagpipes, wild landscapes and wilder warriors – changes from being symbolic of dangerous rebellion in Jacobite times to the globally recognised symbols of all Scotland in the 19th Century thanks to, among others, Sir Walter Scott and Queen Victoria.

Dr Patrick Watt, the exhibition’s curator, joined the NMS team in 2017 and has been involved with the project ever since.

“My role has been content development, choosing items for the exhibition and writing the historical text for each object, making it fun and informative for every age group. It’s been a full-time occupation for the last two years, and there’s been an amazing amount of work across the team,” says Dr Watt, whose background is in Scottish military history.

“We want to bring to life how tartan, bagpipes and rugged, wild landscapes became established as enduring, internationally recognised symbols of Scottish identity. The exhibition explores the efforts made to preserve and revive Highland traditions in the wake of post-Jacobite persecution, depopulation and rapid socio-economic change,” he continues.

“It also shows how Scotland’s relationship with the European Romantic movement transformed external perceptions of the Highlands and was central to the birth of tourism in Scotland. These developments would in turn influence the relationship between the Hanoverian royal family and Scotland, particularly George IV and, later, Queen Victoria.

“We wanted to make Wild and Romantic the best visitor experience as possible and make it relatable to people today by making history relevant to today.”

Complemented by films and interactive digital displays, the items on display relate to significant Highlanders; Queen Victoria and Prince Albert; King George IV; Sir Walter Scott; Robert Burns; painters JMW Turner and Henry Raeburn; Felix Mendelssohn; William and Dorothy Wordsworth; Ludwig van Beethoven and Lord Byron, whose 1807 poem Lachin y Gair (Lochnagar) is quoted in the exhibition’s title.

“This is a contested, complex history, and also a fascinating one,” says Dr Watt.

“Even today there are competing claims over the extent to which those symbols of Scotland we see today are Romantic inventions, or authentic expressions of an ancient cultural identity.

“Using material evidence, the exhibition examines the origins and development of the dress, music, and art which made up the Highland image.”

The truth about tartan, the birth of Scotland’s tourist industry and the adoption of the Highland soldier into the British Army all feature large in the exhibition.

“We show how cultural traditions were preserved, idealised and reshaped to suit contemporary tastes against a background of political agendas, and economic and social change,” says Dr Watt.”

With exhibition text in both English and Gaelic, visitors can learn about the Ossian controversy, the over-turning of the ban on Highland dress, King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822, the Highland tourism boom, and the creation of a Romantic idyll for Queen Victoria at Balmoral.

“The Romantic period undoubtedly coloured perceptions, both at the time and to this day to the extent that the popular images of Highland culture are sometimes dismissed as a 19th Century fabrication,” reflects Dr Watt. “However, the exhibition stresses the deep historical roots underpinning the Romantic image, from the heritage of clan tartans first introduced in portraiture in the extravagant dress of the Laird of Grant’s piper and champion painted by Richard Waitt in 1714, to the bagpiping tradition introduced by oldest known Scottish chanter, which belonged to Iain Dall Mackay, a piper and composer born on Skye in 1656.”

Following the final defeat of the Jacobites in 1746 at the Battle of Culloden, there were reprisals across the Highlands. The power of the Clans was dismantled, male civilians were banned from wearing Highland dress, and Gaelic culture was disparaged. However, the ban on tartan did not apply to those men who enlisted in the newly-raised Highland Regiments of the British Army.

“The heroic image of the tartan-clad Highland soldier went on to become an icon of the military power of the British Empire, and the ideal of the heroic Highland warrior would recur throughout the 19th Century,” explains Dr Watt.

In the 1760s Highland schoolmaster and poet, James Macpherson, claimed to have researched, collected and translated the fragments of ancient poetry of Ossian, a legendary third century Gaelic bard.

“Despite a raging controversy over its authenticity, MacPherson’s work was translated into multiple languages and admired by many influential European writers, artists and composers,” says Dr Watt.

A first edition volume is on display, as well as artwork inspired by Ossian, and the Red Book of Clanranald, one of the Gaelic manuscript sources Macpherson consulted.

Visitors can also see a score of Robert Burns’ Highland Harry in the original hand of Ludwig Van Beethoven. “Burns travelled the Highlands, looking for poetic inspiration and his publisher, George Thomson, commissioned major European composers to set Scottish songs to music, Highland Harry,” says Dr Watt.

And if you thought tourism was a modern phenomenon, look no further than the 1815 oil painting Landscape with Tourists at Loch Katrin by artist John Knox.

“From the late 18th Century, visitors were drawn to Scotland in increasing numbers, attracted to locations depicted in romantic paintings, prints and literature,” explains Dr Watt.

“Many artists, writers and musicians visited, often on personal pilgrimages inspired by the lasting influence of Ossian, or the fame of Burns, Sir Walter Scott and others.”

Dorothy Wordsworth’s travel journal, Mendelssohn’s sketchbook and his original score of the Hebrides Overture, and a silver urn gifted from Byron to Scott after the two literary giants met in 1815 all feature in the exhibition.

“Seeing change all around them, influential Highlanders made efforts to preserve elements of traditional Gaelic culture, at the same time as promoting a new rural economy whose human impact we now know as the Highland Clearances,” he says.

“The exhibition looks at the early Highland societies, and their material legacies, including the standardisation of the Great Highland Bagpipe which we know today, and the codification of clan tartans, through the first gathered samples dating to 1815.

“With the Jacobite cause extinguished as a political and military threat, the Hanoverian Royalty began to embrace and champion their own Stuart lineage, and gestures were made towards healing the divisions of the previous century,” explains Dr Watt.

“This was shown most vividly in the Highland pageantry associated with the events stage-managed by Sir Walter Scott during King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822. A parade of ceremonial costume offers a flavour of spectacular, if controversial, visit by King George IV in 1822.

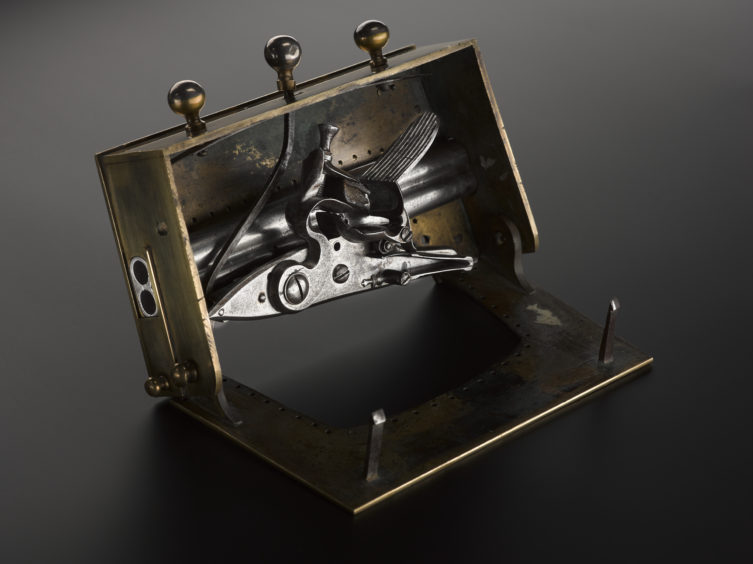

“Stage-managed by Sir Walter Scott is also includes contemporary accounts and the tartans and weaponry which Scott encouraged people to wear for the occasion.”

It was the young Queen Victoria who took this royal fascination to new heights.

“Following a series of royal visits to the Highlands, the Queen and Prince Albert acquired the Balmoral estate. Later, explains Dr Watt, with the death of Prince Albert, the estate became a Highland retreat from the realities of court and government for Queen Victoria.

“Balmoral helped to ensure that the ideal of the Scottish Highlands which emerged from the culture and politics of the late 18th Century would endure, even as fashions and attitudes to history changed,” he says.

“Among the objects on display will be a tartan dress worn by a young Victoria, a brooch she gifted to famed piper John Ban Mackenzie and a mourning pin she had made to commemorate her Highland servant, friend and confidant John Brown.”

Highlights for Dr Watt include the Alexandria Trophy from the Black Watch Museum – a magnificent silver vase presented by the Highland Society of London to the Regiment to mark their contribution to the battle of Alexandria in 1801.

“With fantastic highland imagery and lions, sphinx and African imagery, it highlights military Highlandism,” he smiles.

“I also love the chanter that Robert Burns got from the braes of Atholl, made from a sheep’s shinbone.

Rightly proud of the exhibition, Dr Watt says: “We have been very thorough and cast our net wide. You could easily spend a day exploring the different layers of the exhibition but even a quick walkthrough will give you a true sense of a sense of Scotland and its national past.

Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland, NMS Edinburgh until November 10. Adult £10; child (5-15) £7.50