I was 10 when I learned the police couldn’t help me.

Or rather, that they couldn’t help much after the fact.

I learned this when I woke to find a grown man who was not my dad in my room, in the middle of the night.

Raking in my CD collection. Looking for something to take. To steal. To sell.

There was a man in my room.

I was 10.

But it took three hours after my throat-ripping scream scared the thief’s hands off my mouth; after that sent him shooting back down the stairs and out the door he’d snuck in; after my father had chased him as far as he could down through the street, for the police to show up.

Only then, at 5am on a random 10-year-old day, faced with a notepad full of questions and a woman saying gently ‘we can’t do much with a footprint’, did I realise nothing would be done.

Because it was too long after. And in the grand scheme of things, the crime was petty.

I, the victim, was ‘unharmed but shaken’; a phrase I’ve read in hundreds if not thousands of news reports.

The stolen goods weren’t valuable – a wallet, an mp3 player, some headphones.

It was, as the neighbours would go on to reassure me, “probably just some junkie chancing his luck. He wouldn’t have meant any harm, really”.

His hands were on my mouth. Stifling.

When they came back the next day, the police brought a booklet full of laminated mugshots for me to flip through.

The small mercy of this was after dozens of sketchy-looking Caucasian males, I couldn’t remember the face that had been inches from mine just 12 hours before.

The investigation stopped there. There was, after all, nothing else they could do.

The first ‘petty’ crime – but not the last

I’ve had a fair few instances of ‘petty’ crime happen to me since then, though none so dramatic.

Your routine ‘being a girl’ stuff – threatening catcalls; workplace gropings; street theft; spiking.

Every time, I’ve come away with no bruises, no blood spilled. No harm done.

Except that yesterday I was scared to walk past a tall van parked next to the narrow pavement, because if the (oblivious) man walking behind me decided to attack me right then, no security cameras would see.

There’d be nothing they could do.

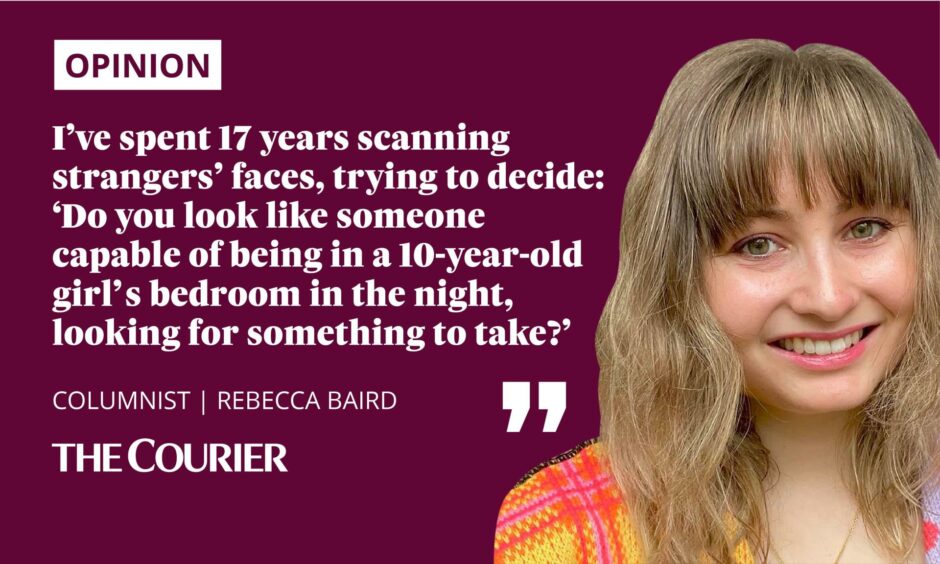

And I’ve spent 17 years scanning strangers’ faces, trying to decide: ‘Do you look like someone capable of being in a 10-year-old girl’s bedroom in the night, looking for something to take?’

They all do, if I look at them long enough. That’s what experiencing low-level, ‘petty’ crime does: makes you so bitter, so capable of believing the worst in people.

And partly, that’s because petty crime so often goes without punishment.

Police are useless when comes to these problems – and the saddest part is, they know it.

Cops too caught up to catch criminals

It’s why a police officer seeing and stopping a thief mid-theft – their job, surely? – was newsworthy in our community this week.

Man who tried to steal Dundee taxi caught by off-duty police officerhttps://t.co/RIvYJu6m7K

— Evening Telegraph (@Evening_Tele) April 14, 2022

It’s why yesterday, when an officer chapped my door and asked me if I knew anything about any suspicious behaviour recently outside my building, I started off pleasantly surprised.

There’d been some car vandalisms, she explained. She wanted to know if I’d seen anything.

I had actually, I told her. Just last week some guy was circling some of the cars. I thought he’d lost a ball or something, but he didn’t seem to have a dog.

“Ah,” said the officer, who was lovely and professional and clearly very diligent.

“That’s strange, but we’re actually following up these reports from about two or three…”

Reader, I really thought she was going to say ‘weeks’.

“… months ago. Did you see anything then?”

I didn’t live here then. I explained as much.

She told me not to worry, that if I saw anything suspicious I should call 101 and let them know, so they could investigate.

“What, in two-three months?” is what I didn’t say.

Her face, as she watched me refrain from saying that, was what I imagine my own looked like when I worked in a call centre and someone would say: “I know this isn’t your fault personally, hen.”

Gratitude, mixed with a deep, frustrated powerlessness.

Or maybe that’s just how I feel.

It’s not the nice cop’s fault the system is so bound by red tape, so crippled by a lack of bodies and hours and resources, that she cannot effectively do her job – which is to make communities safe.

Low-level crime, the kind that makes us build our fences a little higher against the ASBO teens, that makes us buy pink knuckleduster keyrings for walking home, that has us double, triple-checking the door is locked – isn’t the kind that can be fixed after the fact.

Punishment is no deterrent when the perpetrator is desperate, disenfranchised and downtrodden.

After is no use; we must build better before

In fact, part of what makes ‘petty’ crime so scary is that it’s very rarely personal.

The drunk battering down the wrong door does not mean to scare the young woman living alone inside. The glass-smashing youths have no specific vendetta against your dog’s paws.

The addict in your child’s bedroom does not wish to harm her.

These crimes are borne of poverty; homelessness; untreated substance issues; poor mental health.

They are systemic, ingrained, and can’t be cured by the toothless threat of police punishment.

I should know.

The cure for this, then, is prevention; and prevention happens in policy.

Voters can fight crime in our communities not with the cops, but with the ballot box.

We must create a better before, to cure the awful after.

We need to make a world less desperate, and less lost and less poor.

A world less petty.

And I am imploring anyone reading this to use your vote and take that world with you to the ballot box when local council elections come around next month.

Because last night something in my building clattered around 2am and I haven’t moved a muscle since. I can’t. My body won’t move.

It’s been 17 years.

It wasn’t petty to me.