From Ebola in West Africa in 2014 to the ongoing global impact of Covid-19, outbreaks of rare and new infectious diseases are happening more often.

Now ‘monkeypox’, another new infection with a scary name, is in the news.

Naturally, we think: what is this, why has it happened, and what new risk do we face?

We don’t have all the answers yet, but it is important to summarise what we know, in order to understand the situation and manage the risk.

So, what is it?

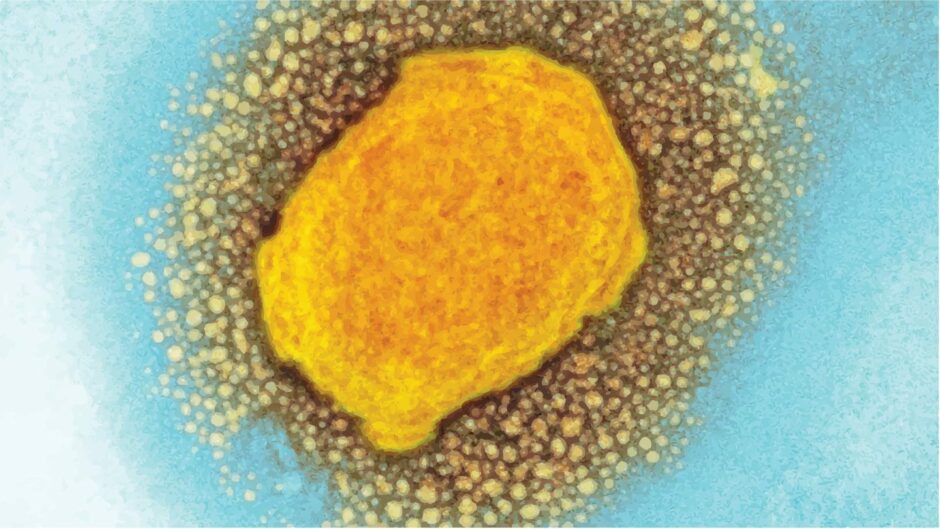

Monkeypox is a virus, first identified in laboratory monkeys.

Human infections have been reported since 1970, mainly in people living near African rainforests, with scattered cases elsewhere related directly to travel or contact with animals.

However, from May 7-23, 56 people have been diagnosed with monkeypox in the UK.

Numbers continue to rise daily, and the first case has now been found in Scotland.

These people aren’t all linked to one another, and most haven’t been abroad.

A similar pattern has been identified in other countries, so local and international public health organisations are watching closely.

Is monkeypox dangerous?

The illness can start with flu-like symptoms, but the main sign is a rash with fluid-filled blisters (a bit like chickenpox) that scab over after two to three weeks.

While this can be unpleasant, life-threatening disease isn’t common.

So far, none of the recent cases have died.

There are two known strains of monkeypox.

Early evidence on the currently circulating strain suggests it to be like the one which caused fewer deaths in prior outbreaks.

How do you catch it and how is it treated?

Monkeypox is mainly transmitted by direct contact with infected skin or inhaling infected droplets at close range.

It can be passed on through bedclothes or physical contact, including during sex.

The virus isn’t thought to spread easily between people unless there is prolonged direct exposure.

A bit like Covid-19, healthcare workers should wear protective clothing to assess and collect fluid samples from the rash.

Isolation from others is important until laboratory results come back.

If monkeypox is confirmed, specific treatments are not well-proven or widely available yet.

However, a vaccine previously developed against smallpox can protect those who have been close to a confirmed case.

Will there be another pandemic?

Recent experience has taught us not to under-estimate infectious diseases or make confident predictions.

The emergence of monkeypox is concerning.

That said, previous outbreaks have been controlled by contact tracing and targeted vaccination.

As the monkeypox virus (MPX) outbreak continues, a lot of data emerging in real-time & being rapidly disseminated (as well as misinformation). I complied the unfolding scientific data (with direct links to papers and threads) on what we (don’t) know so far. #IDTwitter 🧵(1/n)

— Muge Cevik (@mugecevik) May 21, 2022

The virus is very different from the one which causes Covid-19 and there is no known link between them.

Presently, most scientists don’t think the current situation will develop in the same way.

Instead, our experience of Covid-19 will help us.

We should remain diligent about handwashing and giving each other space in public.

Our healthcare teams are well-practised at wearing protective equipment and arranging contact tracing or targeted vaccination programmes at short notice.

Be wary of monkeypox misinformation

During the Covid-19 pandemic, news and social media channels have been flooded with information, some of which was wrong and dangerous.

Similar misinformation is already happening with monkeypox. So we should only listen to advice from proper public health sources.

Monkeypox has previously been most common in Africa.

Recent UK cases have been more frequent amongst who people who identify themselves as gay, bisexual, or men who have sex with men.

It is essential that health anxiety does not – even accidentally – fuel racist or homophobic discrimination.

Working calmly together is the best way of learning about and dealing with new threats.

If we do that, we will overcome this problem more quickly and safely.

Dr Derek Sloan is a Senior Clinical Lecturer in the School of Medicine at the University of St Andrews, and Consultant Infectious Diseases Physician for NHS Fife, where his work includes planning for and management of infectious disease outbreaks.

Conversation