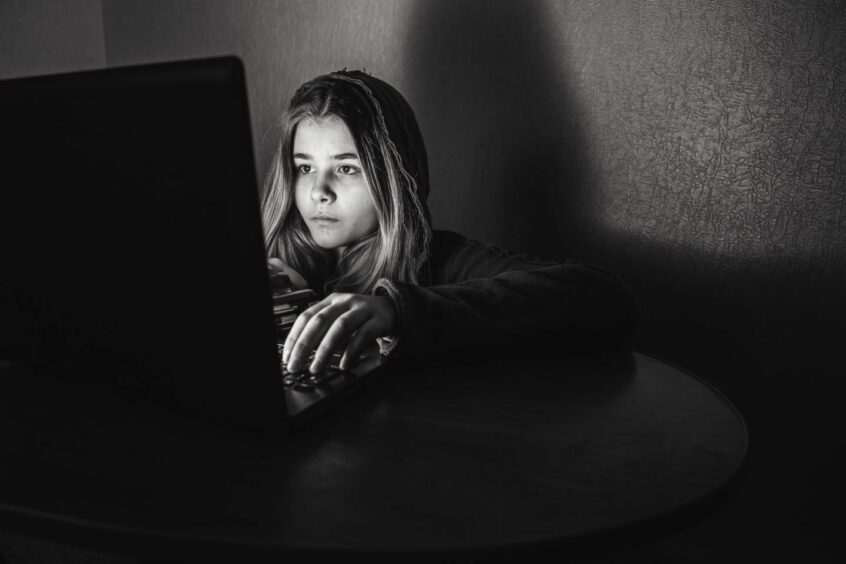

Worrying new research by insight agency Revealing Reality shows that over one third of girls have been asked to share a nude image of themselves when they were 13 or younger.

The poll of over 5,000 school children shows that sharing intimate images has become a routine experience for young people, with six in ten girls and three in ten boys saying they have been asked to share a naked photo with somebody else.

I have an eight year old daughter and I’ll admit I feel wholly unprepared to deal with the issues that I know are rapidly heading down the track towards us.

When I was a teenager, sharing intimate images wasn’t a thing. When we did get mobile phones, the most you could do on them was play snake or send text messages at 20p a pop.

We’re in a different world now: where being asked to reveal intimate images of yourself is a normal request from somebody you are romantically interested in.

It’s perhaps no surprise that the research also showed that boys and girls tend to share nudes for different reasons and that girls’ experiences of nude image sharing is more frequently negative.

Girls from disadvantaged backgrounds have the most negative experience of all with researchers describing these differences across socio-economic lines as “striking”.

These girls receive more unsolicited nude images than any other group, are asked to send images more often and suffer greater reputational damage when they do.

‘Pressure to send images’

As well as a survey, the researchers also interviewed young people to better understand the data themes that they had uncovered.

One comment, from Ellie, a 16-year-old high school student, broke my heart into a thousand pieces.

She said that one reason she sent intimate images was so that she could ‘check’ the boy she was speaking to found her body attractive before they met in person for the first time.

“You don’t want to end up leading somebody on,” she said.

She admitted that sometimes she felt pressured to send images because she was worried that he might lose interest if she didn’t.

‘Pornified hellscape’

This is one of the reasons why adults who complain about comprehensive sex and relationships education in school boil my blood.

Our young people are growing up in a pornified hellscape of our creation and we don’t do nearly enough to help them navigate it.

Gatekeeping information about healthy relationships, sex and consent doesn’t keep kids ‘innocent’, it just leaves them unprepared.

Our society tells girls that their bodies are both sexual and shameful. They live in a world where their peers can access instantly-available hardcore pornography and women are often shown as nothing more than a passive vessel for a man’s pleasure.

Is it any wonder they feel so much pressure to share intimate pictures of themselves?

‘We’ve got to talk’

These conversations are tough, especially for a generation of parents whose experience of sex and relationships was largely analogue.

But we’ve got to talk, otherwise we’re leaving our kids to work it out for themselves or learn distorted truths from peers and the internet.

When my daughter was born, I was determined to be an honest source of information for her.

At first, it was easy. I always used the proper names for all body parts. Discussions about periods were as normal as chats about teeth brushing. I taught her that her body is her own and she is in charge of it at all times.

But I’ll admit, I did swerve the ‘where do babies come from’ question a few times.

I was surprised at my own squeamishness but flashbacks of my own woeful Catholic school sex education made me certain I could do it better.

I finally bit the bullet a few months ago, with help from a few books I ordered.

When they arrived, I skipped past the pages about periods, puberty and body image, knowing that we’d covered most of that ground and there wouldn’t be any great surprises.

The two-page spread on the mechanics of baby-making shocked me a little with its candour.

Important to answer questions honestly

There were no euphemisms, no mentions of ‘special cuddles’ and no impenetrable scientific gobbledygook.

The fact that it made me – as a 32-year-old mum – a little uncomfortable reminded me why it was so important to set aside my own embarrassment and answer her questions honestly.

We read bits of the book together and she read some alone.

Afterwards, I asked her if she had any questions.

Her only comment was that she was pleased to have her new books because she had always wondered what an Adam’s Apple was.

Go figure.

That was just the first conversation but there will be many more over the years.

As they become more digitally independent, our young people will grow up facing challenges that their parents never had to navigate.

The very least we can do is give them the tools they need to get through it as best they can.

KIRSTY STRICKLAND: Your children will have sex – and that’s not the worst of it

Conversation