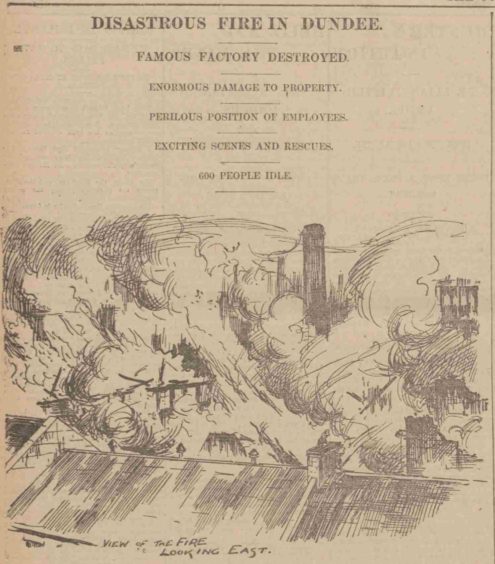

It was the Dundee chocolate factory fire which crushed the dreams of a generation of sweet-toothed children. Gayle Ritchie looks back at the Keiller factory blaze of 1900.

The sticky smell of burning chocolate filled the air as Dundee’s famous confectionery factory burned to the ground.

An almighty inferno – ignited by an exploding fridge – ripped through candy king Keiller’s premises on Albert Square 120 years ago.

The blaze caused the equivalent of £10 million worth of damage in today’s money, and threw 600 people out of work.

A report in The Courier at the time described the fiery spectacle as “awe-inspiring”, with “tongues of fire” shooting from windows and “belching forth to the height of 100 feet”.

Panic-stricken workers escaped through the windows while some had to be rescued by firefighters.

“Looking down on the ruins of what was once Keiller’s great confectionery works, the scene was most deplorable,” the Courier report stated.

“The building in the centre had completely collapsed, and nothing but the walls stood with gaping windows, looking gaunt and smoke-begrimed.”

Destruction of the seductive confection

The Keiller factory on Albert Square was one of the largest in Scotland, employing around 600 people.

It had first opened in 1870 but the firm – wholesale confectioners, fruit preservers, and cocoa and chocolate makers – had recently revamped the premises, kitting it out with costly modern machinery for the production of the famous Keiller’s cocoa and chocolate.

The fire broke out at 3.10pm on May 10 1900 in the chocolate department of the three-storey building situated at the side of the works.

The Courier report stated: “About 50 girls were employed in the department and they were suddenly alarmed by the refrigerator, used in the manufacture of the confection, bursting.

“The place immediately filled with smoke and the females were panic-stricken.

“To add to their dismay, some chemicals lying near caught fire, and ere the girls were well aware of the fact the flames were shooting hither and thither amongst them.

“Soon the powdery material which goes to make up the seductive confection was destroyed and the building itself was in flames.”

A hue and cry

The Courier report stated that a “hue and cry” got up, “panic prevailed” and “consternation” spread as the burning building filled with smoke.

One girl, on hearing the explosion, fainted and fell to the ground.

Some workers jumped out of windows, while others stood in terror waiting for assistance.

On witnessing the situation, Peter Fisher, a bookbinder with Stevenson Brothers, borrowed a ladder from his employer’s works rescued the girls from their precarious position.

They were eventually all brought to safety before the “conflagration spread with alarming rapidity”.

Explosion after explosion

The Central and Harbour Fire Brigades were reported to have “turned out smartly”.

However, soon the centre of the works, where the lozenge department was situated, was ablaze.

Here, explosion after explosion was heard, intermingling with the crashing of falling walls and debris.

Soon, despite the herculean efforts of the firefighters, the inferno raged out of control and the buildings collapsed.

“After the fire had raged about an hour, it appeared that the whole place would be destroyed,” stated The Courier.

“No sooner had the firemen apparently made one place secure than another part of the building became enveloped, and the flames, as they caught hold of the sugar bags, belched forth to the height of about 100 feet. “

By 5pm, the burning mass was getting worryingly close to public offices in Albert Square and Commercial Street, forcing many tenants to remove themselves and their belongings to a place of safety .

When it became apparent the building was doomed, the firefighters turned their attention to saving the company’s offices.

As the burning material was carried by the wind, a child in a bassinet – a type of buggy – was burned, as were several onlookers.

So intense was the heat that a thermometer in Commercial Street registered 136 degrees.

However, the north-east entrance to the works was described by The Courier report as a comparatively “picturesque scene”.

“Great streams of water were coming pouring down seeking their way to the common sewer,” it stated.

“One of the police remarked to a Courier representative that this ‘would be nearly sugarelly water’.”

Sweet-toothed dreams shattered

William Boyd, the managing director of Keiller’s, stated that £50,000 would cover the damage, including machinery and buildings – that’s around £10,000 million in today’s money.

He estimated that a further £5,000 of material had been lost in the chocolate department.

A large stock of confectionery, preserved fruit and marmalade had been in the stores.

Dundee-based historian Dr Norman Watson said the blaze sent a message that buildings for the “new” century had to be different.

“The 20th century began in Dundee like so many of the other 19 – with the town in flames,” he said.

“The Keiller’s confectionery fire of 1900 caused £10 million worth of damage at today’s values and made 600 workers idle.

“It wiped the Albert Square factory off the map and demolished the titbit hopes of a generation of sweet-toothed children.”

Mindful that the Keiller’s factory had burned down, great pains were taken to fireproof the new DC Thomson headquarters then under construction in Albert Square, said Dr Watson.

“More than 200 tons of concrete-covered steel framing was fitted and wood was not used in any part of the main structure, including the roof.”

It was not just the physical side of the town that was changing as the 1800s moved over for the new century, added Dr Watson.

“The Edwardian period saw an ambitious, confident Dundee coming into its own,” he said.

“Discovery was launched in 1901, the Esplanade opened in 1903, Ernest Shackleton stood for Parliament here in 1904, DC Thomson was formed in 1905, Winston Churchill was elected its MP in 1908, the School of Art was founded in 1909 and the city’s first cinema opened in 1910. Exciting times!”

Keiller empire

Keiller was at one time the largest confectionery firm in Britain, as well as boasting eight bakery shops in Dundee.

The firm was believed to be the first, in 1929, to produce Dundee Cake commercially and give it the distinctive name.

It gained a licence to produce Toblerone in the UK from 1932.

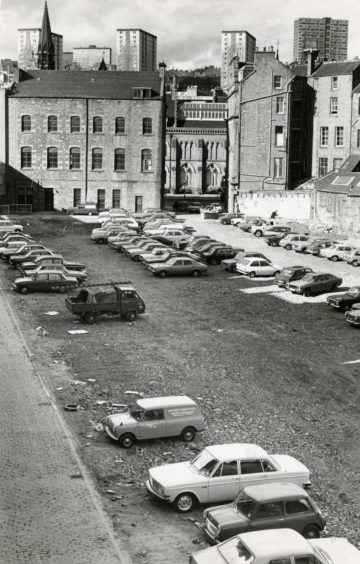

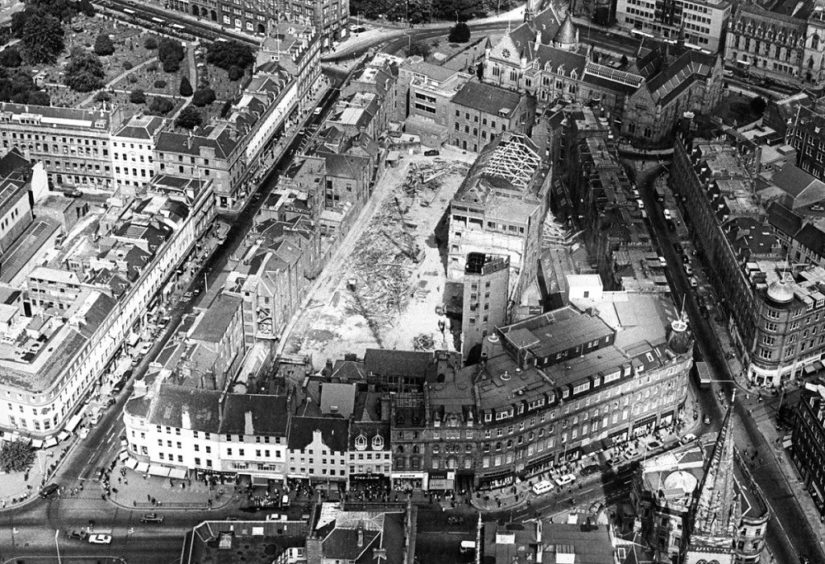

Operations closed at the Albert Square factory in 1947 and the site was demolished in 1972 to make way for the Keiller Centre – which has also been known as the Forum Centre – in the heart of Dundee.

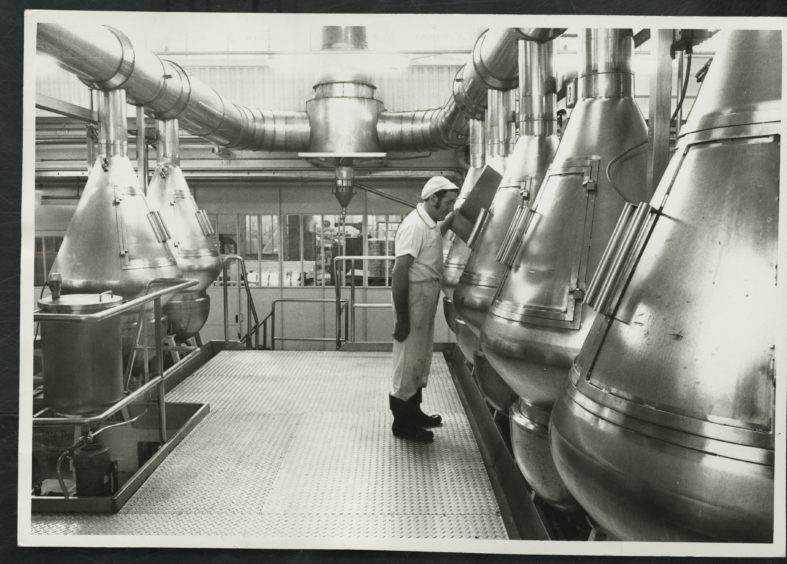

However, in 1928, Keiller moved part, and later all, of its production to a wedge of land on Mains Loan.

The site produced Keiller’s famous marmalade and confectionery including boiled sweets and butterscotch.

Loved by the royals

The firm was favoured by the royal family who frequently visited the Dundee operations.

King George V and Queen Mary visited the Albert Square factory in 1914 and were gifted bags of caramels.

In 1931, the firm supplied King George V with marmalade and Queen Mary with chocolate by royal appointment.

Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip visited the factory in June 1955 and Princess Diana went along in September 1983.

The Princess of Wales was pictured donning the regulation white hat and Keiller-branded white coat while chatting to staff and receiving a gift of preserves and confectionery during her visit.

Despite employing nearly 900 people during the 1950s, the Mains Loan factory’s final owners – Alma Holdings – went bust in March 1992 before the plant was sold off.

It was demolished in 2018 following a spate of vandal attacks and fires.

Earlier this year, Barratt North Scotland applied to build 230 properties at the site.

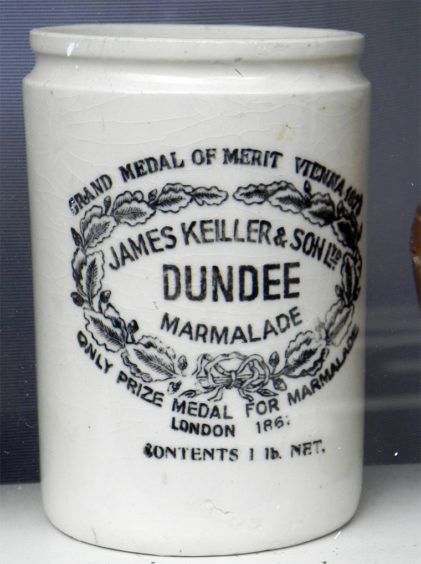

Dundee Marmalade

Dundee is renowned for the three Js – jute, jam and journalism.

The “jam” association refers to marmalade, which was purportedly invented in the city by Janet Keiller in 1797.

Janet and her husband, John ran a cake and sweet shop in the city.

One day, faced with a consignment of unwanted bitter oranges sold to John by an opportunist Spanish shipmaster who knew a good con when he saw it, Janet boiled them up to make the first peel, or “chip” marmalade.

This new product was a great success and took its place beside the cakes and confections.

In 1797, when Janet and John were both 60 years old, Janet set up in business with her son, James, trading initially as “James Keiller” and changing to “James Keiller & Son” in 1804.

When the menfolk died, Janet and her daughter-in-law Margaret successfully ran the business.

In 1850, Margaret organised a move to the shop at the corner of Castle Street, where you can find a plaque dedicated to Janet.

A factory nearby, on Albert Square, ensured there was plenty of space to stock supply jams and marmalades.

One of Janet Keiller’s great-great-great grandsons was Alexander Keiller, the noted archaeologist, and one of her great-great-great-great grandsons is the British television presenter Monty Don.

James and Janet Keiller are buried in the Howff Cemetery in central Dundee.