It was a night when many families across central Scotland anxiously awaited the return of their loved ones from a football match.

And it turned into a desperately unhappy New Year for scores of mothers and fathers, sons and daughters and friends and colleagues who clung to the hope that the people they loved and cherished would walk through the door and confirm that they had escaped the Ibrox Disaster.

This was before the atrocities of Heysel and Hillsborough and the modern-day advent of rolling news channels and endless information at the public’s fingertips.

Half a century ago, the telephone was a device in your living room plugged into a socket and if it didn’t ring, there was nothing to do but tap your fingers, watch the clock and wait…

Futile anger

Eventually, on that evening of January 2 1971, the majority of the spectators at the Old Firm derby did come home and those nearest to them sighed with relief.

But, for 66 other families, there was the grim realisation that the catastrophe which had devastated part of the stadium at the end of the contest had snatched away their menfolk, young lads and, in Margaret Ferguson’s case, her daughter.

Decades later, the photographs from the archives reflect the collective mystification and bewilderment, accompanied by a futile anger, that so many lives should have been lost, in the midst of what should have been a festive visit to a sporting occasion.

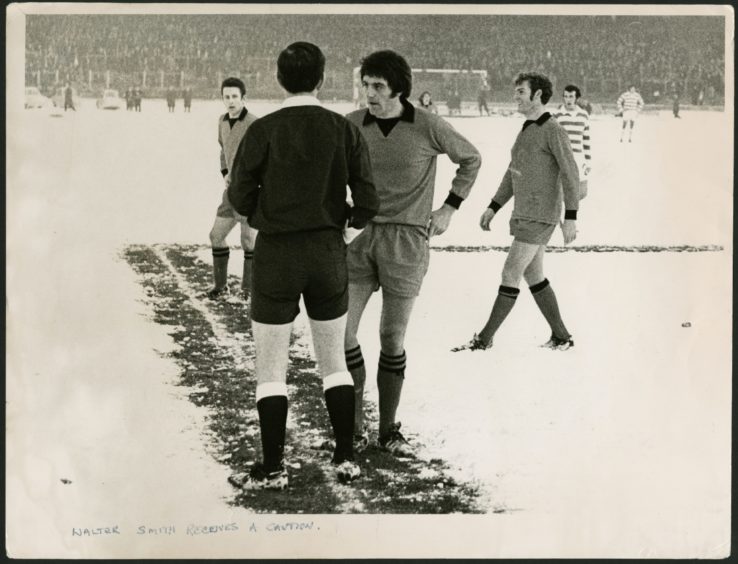

Talk to some of the famous figures who were there at Ibrox on that ghastly occasion, men such as Alex Ferguson, Walter Smith or John Greig, and you will not hear easy sentiments, but hushed voices and instinctive sympathy for victims who, in other circumstances could have been their very selves.

Then prod them gently on their memories and they will relate their accounts of a tragedy which, all too fleetingly, tore through Glasgow’s sectarian curtain and led to Orangemen shedding tears in the company of priests throughout the central belt.

Markinch

The late Sandy Jardine, was among the most eloquent witnesses to scenes which were straight from a Dore painting.

And he once told me in detail how the catastrophic events unfolded while the vast majority of supporters were oblivious to them.

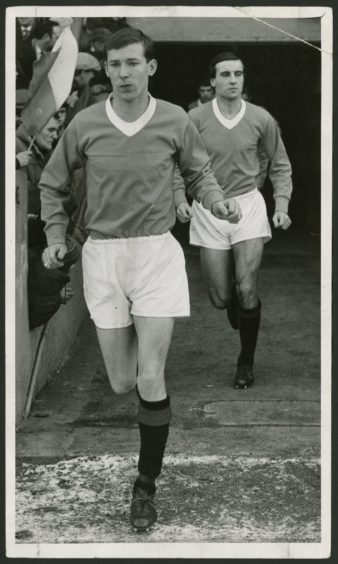

He said: “In these days, this was probably the biggest fixture of the season, given that the Old Firm clubs only met twice a year in the league, but it was dreadfully ironic that what had been a fairly uneventful occasion, with neither trouble on the terraces nor on the pitch, should develop into a walking nightmare for so many.

”Everybody knows the details of how Jimmy Johnstone put Celtic in front with just a minute to go. But then we equalised immediately through Colin Stein and the referee blew for full time immediately.

“So you had Rangers supporters who thought ‘That’s the game over’ when Jimmy scored turning to go down the big staircase, then turning back when they heard the huge roar which greeted Colin’s strike, and that coincided with a massive number of fans making their way towards the exit and the subway.

“Then, suddenly, somebody fell and the whole terrible business began.

”I was on the ground staff, I had actually swept these stairways and they were huge, solid objects, so I could never understand how they could get mangled so badly by any number of human beings. But they were and there are no words to describe it.

”As players, we were completely unaware anything was wrong after the match. We were in the dressing room, sharing a few laughs together before getting into the bath. I was one of the last guys to climb out, but as I re-emerged, the order came that there had been an accident and we all had to leave the room as quickly as possible.

“It could have been a fire alert or anything, but while we got dressed as fast as we could, the authorities started bringing some of the dead bodies into the place and everybody turned grey at the sight. But even then, we had no real idea of the scale of it.

”As I drove back to my home in Edinburgh, I heard there were two dead, but the figures soon mounted up. It was 12, then 22, then 30, then 44 and finally up to over 60.

“The thing was that thousands of the supporters had gone out to pubs or restaurants or picture houses afterwards. They didn’t know about the disaster, so they didn’t know how many of their wives and girlfriends and mums and dads were worried sick.

“Vast crowds assembled at all the drop-off points for the buses. The telephone lines were jammed. Glasgow was in turmoil, the hospitals were packed to overflowing.

”Anxiety, terror, pain, sadness, horror…all these emotions were draped across the country on that terrible night.”

Initial speculation

The initial speculation was that some fans had left the ground slightly early when Celtic scored, but then turned back when they heard the crowd cheering.

However, the official inquiry into the disaster eventually concluded that there was no truth in this hypothesis and declared that all the spectators were heading in the same direction at the time of the collapse.

Yet, it was, to all intents and purposes, a hellish vista. Willie Waddell, the Rangers manager and his Celtic counterpart, had both observed casualties in other spheres, whether in battle or at the coal face, and the pair emphasised the need for entrenched communities to pull together and for religious tribalism to be cast aside.

Sadly, but perhaps inevitably, given the nature of the Old Firm divide, their coming together proved nothing more substantial than a temporary ceasefire.

But Waddell vowed that the dreadful scenes he witnessed would never be repeated at Ibrox and, prior to his death in 1992, that objective had been the catalyst for the creation of a magnificent new stadium – even though Waddell, a tough-as-teak combatant in the Second World War was haunted by the impact of 1971.

As he told John Rafferty, the respected Scotsman football correspondent: “It’s strange what comes into your mind, but when I first went to the top of the steps and gazed down on the pile of bodies, my initial thought was of Belsen, because the corpses were entangled as they had been in the pictures which came out of the concentration camps.

“But, my God, it was dreadful. There were bodies in the dressing rooms, in the gymnasium and even in the laundry room. My own training staff and the Celtic boys were working flat out at the job of resuscitation and we were doing everything we possibly could to bring breath back to these crushed bodies.

”Honestly, I will never forget the sight of Bob Rooney, the Celtic physiotherapist, with tears in his eyes, giving the kiss of life to innumerable victims. He never stopped, nor did the doctors and nurses and ambulance staff who flocked to join them.

”We will never know how many lives were saved in there in that frenzy of activity.”

Under siege

Just a few miles away, the Southern General Hospital in Glasgow was under siege, their switchboard of just 35 lines, plus a single police short wave radio, inundated and overwhelmed by a plethora of panic-stricken calls.

There was nothing to be done in many cases except for the police to visit homes the next morning and impart terrible news. Yet, as is so often the case in these mercifully rare events, the death toll could have been much worse.

Even such redoubtable footballing characters as Ferguson and Walter Smith were close to being involved in the disaster.

And, when they subsequently spoke avoid their experiences, they didn’t sugar-coat their recollections of the darkest day in Scottish football history.

Smith, a registered professional with Dundee United, who later was a pivotal figure in Rangers’ advance to nine consecutive championship titles, was given permission by the Tannadice officials to travel to the Old Firm derby.

And the then 22-year-old was all smiles as he made the journey to the ground of his favourite club.

But he refused to gloss over the horror of what awaited him later that day.

As he said: “I can recall leaving the stadium with my brother at the end of the match. I was on Dundee United’s books at the time, but because of my lack of ability, they had omitted to select me for the New Year match, so I travelled to Ibrox on the supporters’ club bus and I remember there being a wall at the side of the staircase which, if it hadn’t been there, would have allowed people to spill over.

“Both of us got out, and I thought it was because the fencing had collapsed, but on the 25th anniversary [of the disaster in 1996], I looked at a photograph and the fencing was intact. We must have got over the top of other people, although nobody around us was in any danger; the deaths occurred at the bottom of the stairs, but we didn’t know that.

”We got on the bus, which didn’t have a radio or anything, and it was only when I arrived home that I remember my mother crying, saying that people had died.

”If we had left the game two minutes earlier, it would have been us.’

Alex Ferguson

So many others in the stand had similar stories to tell, including the former Aberdeen and Manchester United manager Alex Ferguson – who was playing for Falkirk at that stage of his life, as the prelude to starting his illustrious managerial career.

He said: “I remember leaving immediately after the equaliser went in.

“As we drove home past the hospital, we saw a huge number of ambulances heading towards the ground and thought, ‘Jesus, there must be some trouble going on there’.

“It was only when I got home to my mum and dad’s that we realised what had happened. My brother Martin had been at that end of the ground and still wasn’t home.

“It was only after a few hours later when he turned up that we knew he was okay.”

In the months and years ahead, the disaster spurred the UK government to look into the whole question of safety at sports grounds.

Warning signs

In February 1971, Scottish judge Lord Wheatley was asked to conduct an inquiry and his findings, which were published in May 1972, formed the basis for the Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds, which was released the following year.

It didn’t mean that football grounds became safe places, as repeated tragedies throughout the 1980s in England and in Belgium demonstrated. Yet what happened at Ibrox showed the dangers of ignoring clear warning signs.

in the first week of January, though, that wasn’t the main priority on people’s minds.

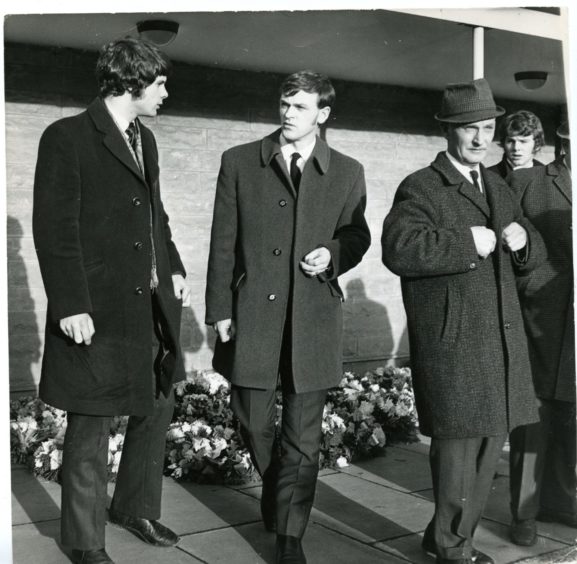

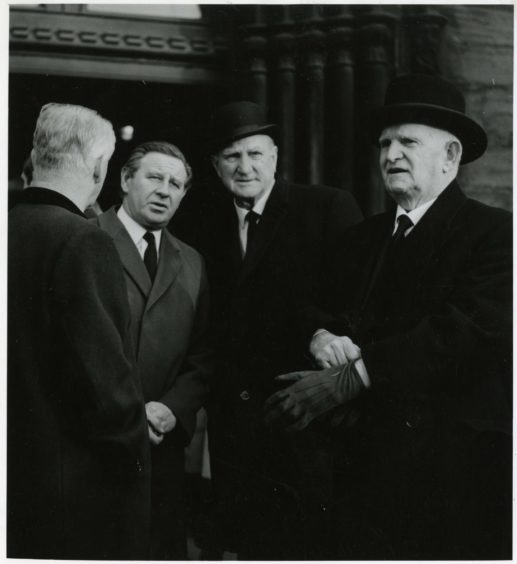

There were funerals to organise, the bereaved to look after and Waddell, who had been horrified by the awful events made sure there were players from his club at all the funeral services.

Yet nothing could dispel the tristesse and tears which enveloped Scotland in these early weeks of 1971.

And nowhere was that more evident than in Markinch where five teenagers, who had laughed and jokes as they travelled from the Kingdom to Glasgow, were laid to rest even as thousands of mourners grieved their passing.