The grisly murders which gripped London with fear during the Swinging Sixties stopped after Dundee man Mungo Ireland took his own life.

Was Ireland the unknown serial prostitute killer Jack the Stripper?

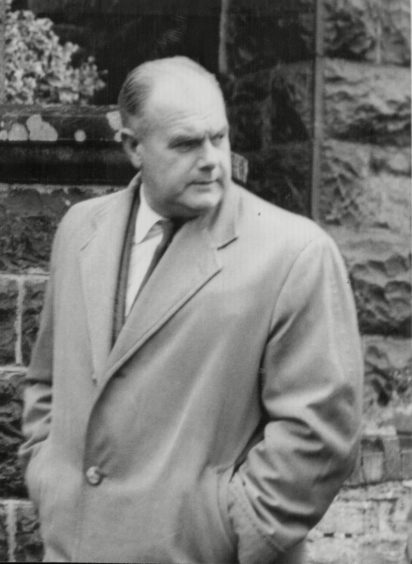

Known as Four-Day Johnny for his speed in solving cases, Detective Chief Superintendent John Du Rose of Scotland Yard, the detective put in charge of the case, certainly thought so.

But did he frame a dead man to avoid being seen as having failed?

Who was Mungo Ireland?

Very little is known of Mungo Ireland.

His paternal grandparents were Mungo Brodie Ireland and Mary Jane Ireland from Dundee.

They had a son David who got married to Anne Johnstone at St Roque’s Church in 1904.

She gave birth to Mungo Ireland on April 17 1919 at 48 Crescent Lane.

He had eight siblings.

The Hammersmith Nude Murders

Ireland was now living in Putney in 1964 with his wife and five children.

The Hammersmith Nude Murders – in which six women were found strangled in varying states of undress between 1964 and 1965 – was one of the biggest manhunts in Scotland Yard history.

The victims were pregnant Hannah Tailford, 30, Irene Lockwood, 25, Helen Barthelemy, 22, Mary Fleming, 30, Frances Brown, 21 and Bridget O’Hara, 27.

It is possible, probable even, that there were earlier victims.

Last to die was O’Hara.

She went missing on January 11 1965.

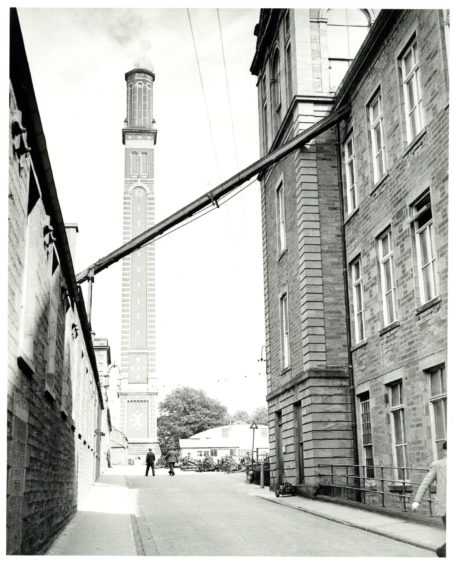

O’Hara’s body turned up flecks of industrial paint after being found on the Heron Industrial Estate in Acton on February 16 1965.

She had been strangled and was missing several of her teeth.

Her corpse was partially mummified, as if it had been stored for some time in a warm place.

John Du Rose

Legendary Scotland Yard investigator Detective Chief Superintendent John Du Rose was recalled from holiday to orchestrate the Jack the Stripper enquiry.

Traces of industrial paint had now been found on four of the victims.

Paint spots were traced to an electrical transformer at the rear of a building on the Heron Industrial Estate.

The building was opposite a paint spray shop and was discovered to be the place where the bodies had been kept.

Ireland was a former security guard at the Heron Industrial Estate.

He was now a foreman cleaner for Jute Industries Ltd in Dundee and stayed with family members in Scotland while his wife and five children remained in Putney.

He arrived back in London the day before O’Hara’s body was dumped.

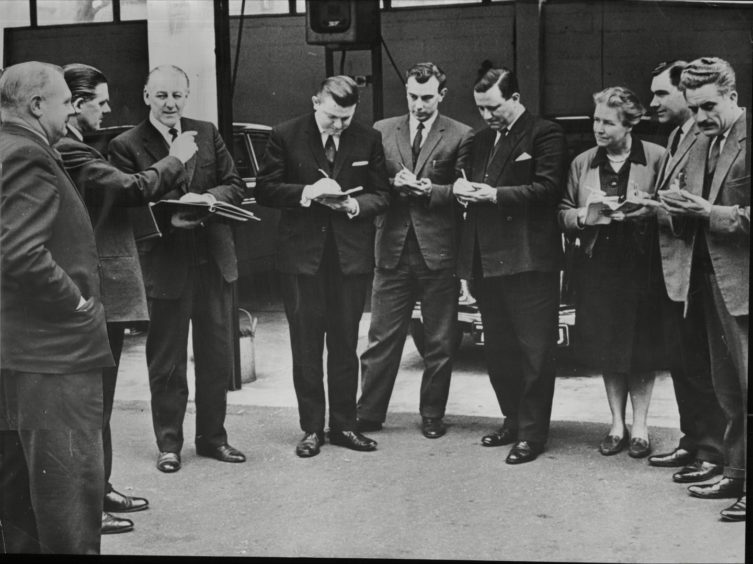

Du Rose later decided to hold a press conference and announced his team had narrowed their suspect list down to just 26 individuals.

He whittled the suspect list down to 10 and then to three in subsequent conferences and suggested the net was closing in on the killer.

Ireland took his own life shortly afterwards by carbon monoxide poisoning.

He fell asleep on the sofa after watching television and his wife Elizabeth went to bed and left him sleeping.

Suicide note was left

Around midnight she heard his vehicle drive off from outside their maisonette in Putney and she went back to sleep.

Ireland left a note for his wife that read: “I can’t stick it any longer.

“To save you and the police looking for me I’ll be in the garage.”

Ireland’s son David raced to the garage and found his father lying across the front seat of his Ford Consul with his head on the steering wheel.

An inquest was held into Ireland’s death at Battersea, London, which recorded a verdict of suicide from asphyxiation after inhaling car exhaust fumes.

Coroner Dr Gavin Thurston said: “It is significant that his death occurred on the morning he was due to answer a summons.

“There had been a change in his habits and general behaviour recently.

“He had been drinking rather heavily shortly before his death.”

However the official inquiry by the police in 1965 concluded that Ireland was in Scotland on January 11 1965 when Bridget O’Hara disappeared.

There was no evidence to connect him with any of the other prostitutes or place him in a position where he had an opportunity to abduct them.

Du Rose first identified Ireland in a BBC television interview in 1970 as a respectable married man in his forties whom he codenamed “Big John”.

He started his career in the police in 1931 and was interviewed on current affairs programme 24 Hours by presenter Tom Mangold to mark his retirement.

Du Rose said: “As time went on, of course we realised that the suspect, whoever he was, must be reading the news of what was going on, the activities of the police and so on.

“And so we got the press and the radio and the television on our side, and we fed them stories every day.

“This was our way of communication with the murderer and we hoped by this means to start him up, to get him frightened, to make him run, to do something, which would point the finger towards his guilt.

“And I think eventually he became so frightened he took his own life.”

Du Rose reiterated the claim in his 1971 book

Du Rose said the unnamed person was already a suspect at the time of his death.

He said: “Now we couldn’t talk to him, he was dead.

“We could only ask questions, check his activities, his movements, where he associated, and so on. And when you bear in mind that there were six takings and six droppings of the body, we had 12 occasions on which to check an individual out.

“A wonderful set of circumstances really to pinpoint an individual.

“Not just one murder…but on 12 occasions this man could have been available to have committed all these murders.

“And even now I am not in a position to name this man.

“He has relatives who are still alive, it would reflect on them.

“It would be utterly wrong and we don’t do that type of thing.”

Du Rose again reiterated his claim in his book Murder Was My Business in 1971.

He wrote: “We could never forget that no woman was safe until the killer was in our hands, but it was not to be and within a month of the murder of Bridie O’Hara, the man I wanted to arrest took his own life.

“Without a shadow of a doubt the weight of our investigation and the enquiries that we made about him led to the killer committing suicide.

“We had done all we possibly could but faced with his death, no positive evidence was available to prove or disprove our belief that he was in fact the man we had been seeking. Because he was never arrested, or stood trial, he must be considered innocent and will therefore never be named.”

Suggestion Mungo Ireland was framed

Du Rose didn’t actually name Mungo Ireland.

However, during research into his book Jack Of Jumps, David Seabrook named the suspect Mungo Ireland and suggested he was framed by Du Rose.

“Police found no evidence of any description to link this man to the murdered women, and the fact he was in Scotland on 11th January, the date of O’Hara’s disappearance, served to eliminate him from the inquiry.

“He ‘will never be named’ because he was framed, his suicide exploited for fame and glory by John Du Rose,” Seabrook wrote in his book.

The Scotland Yard Serious Crime Review Group re-investigated the Hammersmith murders between 2006-2007 which resulted in a new conclusion.

A statement read: “The circumstantial evidence against Mungo Ireland is very strong and it was the view of the officers conducting the most recent review of this case that he was most likely to be responsible.”

Although Ireland’s work records indicated he was in Scotland on the night of O’Hara’s disappearance, Scotland Yard believe it is possible that these may have been falsified.

Child killer Harold Jones

Crime author Neil Milkins said the killings stopped after Ireland’s death and the police task force set up to catch the killer was reduced and finally disbanded.

Milkins, who wrote the book Who is Jack the Stripper?, was an investigative consultant for the BBC documentary: Dark Son: The Hunt for a Serial Killer.

“On the morning that Ireland’s body was found, he had been due to appear before Acton Magistrates Court to face a charge of failing to stop his car after being involved in a road traffic accident,” said Mr Milkins.

“Did Ireland commit suicide to save facing Acton magistrates over a trifling motoring charge or did John Du Rose push him over the edge with his press statements?

“Another puzzling feature is that if Ireland had been a suspect before his suicide why was there no forensic evidence in his car, garage or home to link him with the killings, bearing in mind that he had killed himself only a short time after the last two murders?

“After John Du Rose’s retirement in 1970, five years after the last murder, he claimed he knew who the killer was before Mungo Ireland’s suicide.

“If he knew Mungo Ireland was the killer, why did he interview more than 7,000 potential suspects some two months after Ireland’s death in March 1965?

“I believe Du Rose suggested a dead man was the killer to get the glory.”

Jones was living close to Mungo Ireland

Mr Milkins believes it is Welsh child killer Harold Jones, who was living in Fulham at the time of the murders, who was the infamous serial killer.

Jones was jailed for 20 years in the 1920s after murdering an eight and 11-year-old when he was just 15.

Jones admitted both murders and would very likely have been hanged had he not been aged just under 16.

That none of the women had been sexually assaulted either also ties in with a report written by a senior prison medical officer during Jones’ time behind bars, suggesting that acts of cruelty and killing were enough to give him the gratification he needed.

He was released from prison and was living just two streets from Ireland at the time, and a similarly short distance from three of the victims.

He said: “I would stake my life on it that Harold Jones is Jack the Stripper.”

Jones died from bone cancer in 1971.

Detective Chief Inspector Jackie Malton and Sergeant Alan Jackaman were willing to reinvestigate the murders following a request for the Met to reopen the case.

Sergeant Jackaman said Jones would have shot to the top of the suspect list had he known what he knows now but police have no plans to reinspect the cold case.

The crimes inspired the crime novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern, which Alfred Hitchcock turned into the 1972 movie, Frenzy.