These days, the tattie holidays are a welcome couple of weeks off school, but for Dundee schoolchildren of the past it meant hard labour during the potato harvest.

In the 1930s, 40s and 50s, thousands of youngsters from Dundee were sent out to the fields of Perth, Fife and Angus every October to help with the tattie howking.

Some children went with their parents to help earn an income for the family, but hundreds of others went out as groups with teachers, organised by schools and the agriculture board.

In the days before machinery, tattie howking by hand was tiresome and back-breaking work, and children were cheap labour.

In 1948, almost 4,000 Dundee pupils over the age of 13 were earmarked for the potato harvest, but concerns were raised by the headmaster of Harris Academy.

Rector Alexander Peterkin said two weeks off for tattie howking was becoming disruptive to the education of younger pupils and called for year one to be exempt.

Generally it was the junior pupils that took part in the annual harvest with senior pupils allowed to continue their studies.

Mr Peterkin felt that his school was sacrificing far more pupils than others, and argued with the Education Board that it was becoming problematic.

Especially as it was also pointed out that some pupils who rarely attended school always seemed to manage to get along to the paid tattie howking.

Children could expect to earn 8 shillings a day with a midday meal included.

But for the measly sum of 10 shillings a day, teachers had to endure the prospect of organising legions of tattie howkers, administering the pay, and stand in cold and wet fields, supervising.

Even the city councillors thought it unfair and said it was “ridiculous” teachers were expected to carry out these duties – but they were told if they didn’t it would be “pandemonium” in the fields.

But by 1950, it was decided that teachers were better placed in the classroom and that janitors should take over some of the supervisory duties instead.

Conditions for children were hard; they were expected to work eight-hour days, not inclusive of travel time from Dundee, in all weather conditions.

They would be collected and piled onto the back of farm lorries, and shown to their patch by a no-nonsense farmer.

Sticks and string would mark out the area where children would collect tatties once the digger had ploughed by.

A whole day would be spent on the fields with a break for lunch and a trough of water to drink from.

A report conducted into the physical toll of the Fife tattie harvest on youngsters in 1952 concluded that the toil was actually good for them.

In fact, the director of education said they even witnessed children “practising somersaults between rounds of the digger”.

And that the only adverse affect on the children was on their education.

But despite the labour, there was great camaraderie among the pickers and it was often a happy time for youngsters who otherwise spent their lives in the city.

They would be joined in their toil by men and housewives hoping to earn a little extra income ahead of the winter months.

Other tasks included shifting heavy baskets full of tatties off the fields and into sheds for storage or packing.

Attitudes were changing by the 1960s and fewer children were released from school for tattie howking.

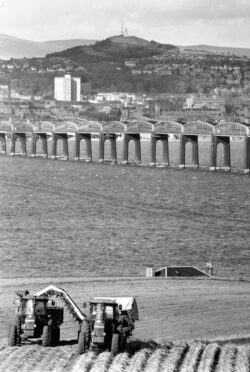

But even into the 1970s and 80s, when technological advances revolutionised farming, a lot of potato picking was done by hand.

By then, the October holidays were a break in the school term for everyone.

Tattie howking was no longer enforced upon children, but many in rural areas still continued to take to the fields to earn a little extra pocket money.

Pupils still enjoy the fortnight off for the tattie holidays, maybe enjoying trips abroad or outings with family.

A world away from the sweat and slog of their contemporaries in decades gone by.