The Rothes Colliery closed 60 years ago, in May 1962, and these striking images show the last visible traces of the pit being demolished.

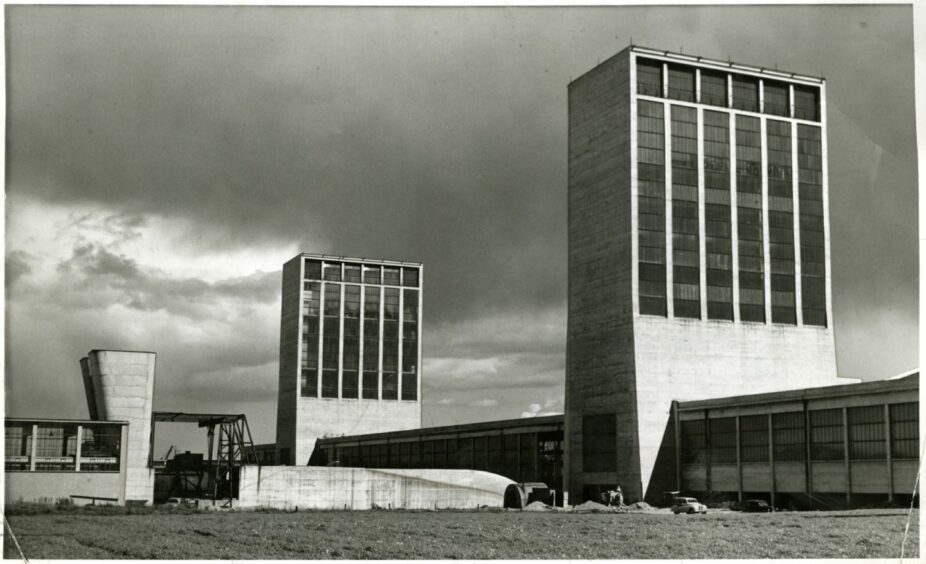

The giant twin winding towers were one of Fife’s most prominent landmarks.

They could be seen from the A92.

The 200ft-high concrete towers which dominated the village of Thornton on the outskirts of Glenrothes were finally pulled down in March 1993.

It was the final curtain call in a drama which started back in 1946.

Back to the start…

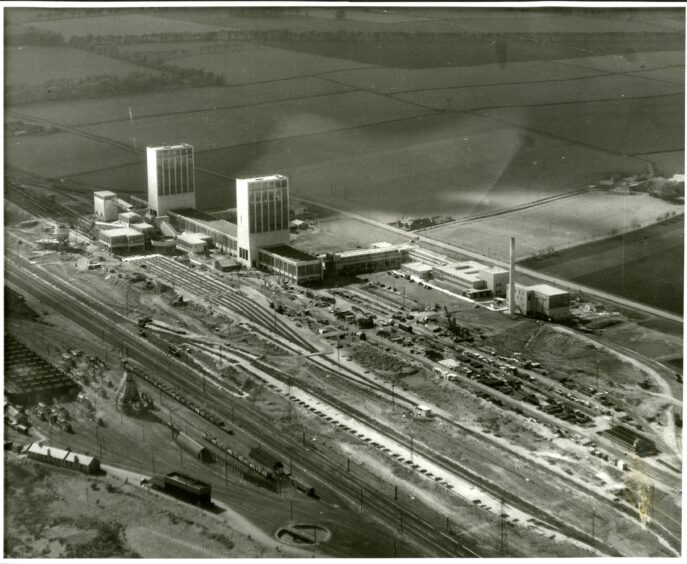

That was the year the Fife Coal Company Ltd began sinking deep shafts on the outskirts of the village and this would eventually become the Rothes Colliery.

The coal mine was planned to be one of the National Coal Board’s ‘super-pits’ with an intended output of 5,000 tons of coal per day.

Glenrothes new town was built in anticipation of its longevity.

It was promoted as being a key driver in the economic regeneration of central Fife.

Developed at a cost of £12 million, the coal mine was expected to produce 5,000 tonnes of coal a day for well over a century.

Its two angular wheelhouses dominated the Glenrothes skyline.

But these towers, acting as a symbol of a successful post-war Britain, soon became a sore reminder of one of the biggest industrial failures in the country’s history.

The Rothes Colliery struggled from the beginning.

In July 1951, seven years before its official opening by The Queen, a large hoppit plunged 1,000 feet to the bottom of the shaft and trapped 22 men at the bottom.

One received several serious injuries and died shortly afterwards.

The hoppit – a large bucket used in excavation work in pits – had been fully loaded with rubble and also caused severe damage to the ground below.

It was a sign of things to come.

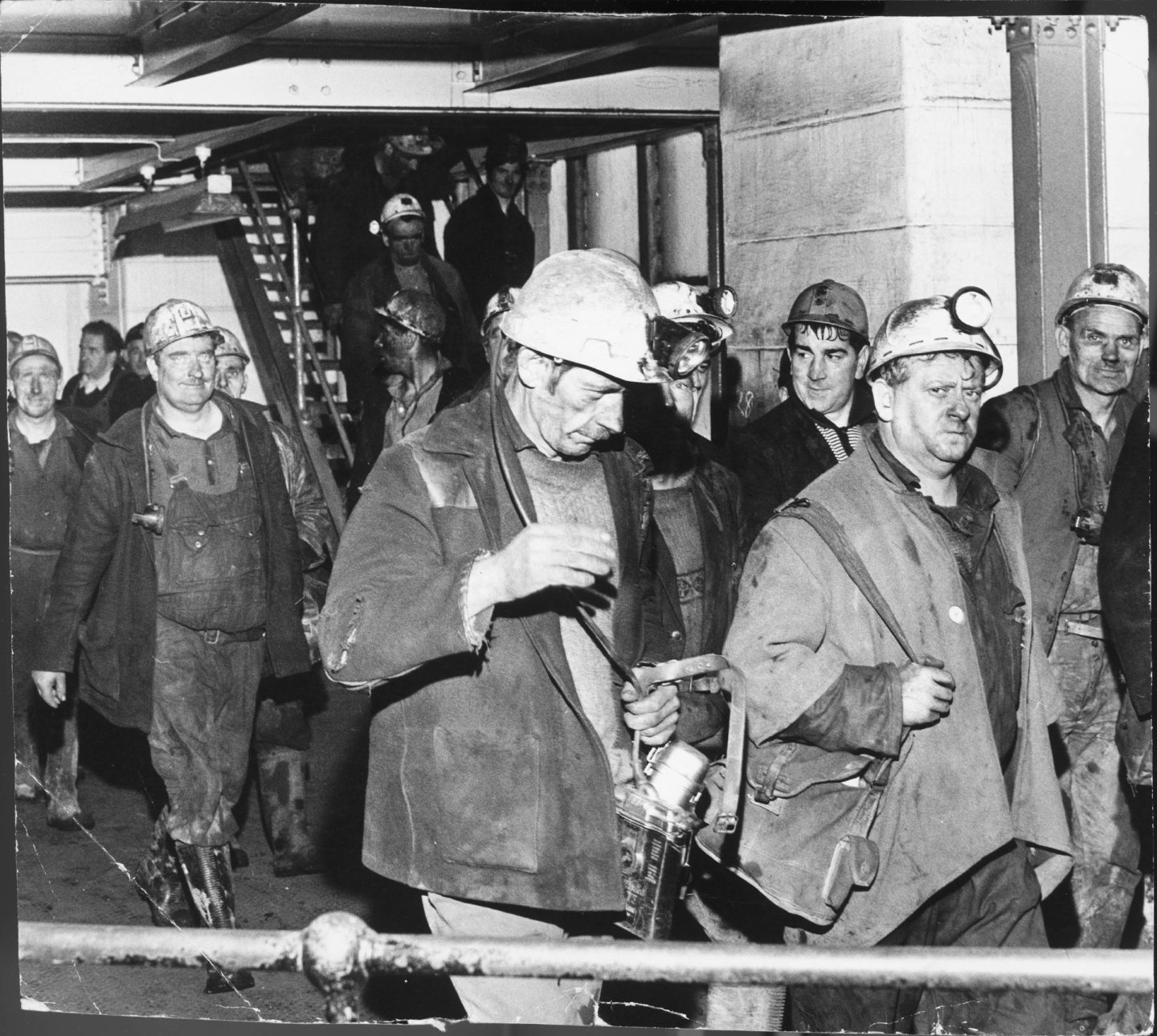

A dirty and dangerous job it might have been but the money was fairly decent.

However, the workers were already in a race against time for their livelihoods – even at this early stage – as the colliery was suffering from flooding.

As the pit was being dug, these same miners were encountering nearly three times as much water as had been expected.

At one period, the inflow of water reached 1,000 gallons a minute.

But the Coal Board were determined that Rothes Colliery would be successful, and it was officially opened as a working mine by The Queen in 1958.

She became the first British monarch to go down a pit.

However, this could have been what sealed the fate of “the Rothes”.

Superstitious miners believed it was unlucky to let a woman go down a mine and were apprehensive about The Queen’s visit, which caused significant attention at the time.

Were they proved right?

The Rothes Colliery closed soon after, in May 1962.

The flooding had proved too significant a problem.

While the miners were hard workers, they weren’t strong enough to battle with Mother Nature and they soon found themselves out of a job.

It was a bitter blow for the workforce and the town.

Its closure seemed a disaster at the time for the 13,500 who lived in the town.

With only eight companies operating locally, many staked their livelihood on the colliery.

The local area also depended heavily on the miners’ spending power, with many small businesses and shops relying on the pitmen’s pounds and pennies.

There was also the development of Glenrothes new town to consider.

The town had been built to support the influx of miners and their families.

What was the point in continuing to develop a town that couldn’t provide any work for its residents?

But the Glenrothes Development Corporation believed that Glenrothes new town was worth the fight.

The corporation’s plan of action centred on a new concept – gone would be the one- industry structure and in its place would be a diversified industry base.

By the late ’60s many major firms had located in the town, like GEC, Burroughs, Beckman Instruments and Hughes Microelectronics.

Glenrothes had become Scotland’s silicon glen.

The town became the administrative capital of Fife and was hailed by a nationwide survey of businessmen as the best new town in Britain.

The Rothes Colliery’s unusual rectangular winding towers were the last visible trace of Glenrothes’ standing as a one-industry town.

They were demolished in 1993.

At the time The Courier spoke to a former steel fixer who had helped to build the towers in the late ’40s.

John McGuinness said: “We always said it would take God Almighty to bring them down.

“When I read they were going to blow them up, I thought they would have some job.

“I know every bit of steel in them.”

Mr McGuinness was right.

Life yet in Rothes Colliery?

The Rothes Colliery towers were demolished in half-hour intervals.

Every 30 minutes the latest wave of dust and rubble filled the skies as the towers were blown apart by several doses of explosives.

As the last brick fell, the rubble was poured down the mine shafts and covered over.

The jewel in the crown of Fife’s coalfield was no more.

However, with energy prices rising, some have advocated a return to coal mining in Britain as a means of fuelling the country into the future.

Despite environmental concerns, industry continues to burn coal, and some from the old colliery have argued that it could be reopened to meet the world’s energy needs.

An excursion to the remains of Rothes colliery, the pit Glenrothes new town was built to serve, but which closed after 12 years due to flooding. A fine example of ‘rural modernism’, the ventilation building may be the sole remaining example of the work of NCB architect Egon Riss. pic.twitter.com/FMD6wHLX28

— Andrew Demetrius (@Demetrius_Art) March 19, 2022

Jim Parker, who was once part of the colliery’s management team, described how simple it would be to get the old mines working again.

He said: “There are two shafts that were excavated and they were strong because money was no object when they were established.

“The tunnels will stand for another 100 years, so if the price is right then it is definitely worthwhile doing.”

Others wondered if the site of the old colliery could be turned into housing for the ever-expanding Glenrothes community, which has since gone on to house a population of around 38,000.

Whatever the future holds for the site of the old mine, it’s unlikely to be as visually striking as the industrial twin towers from the 1950s were.

More like this

Why Glenrothes is the street fighter of Scotland’s new towns

Coal Country: The stories behind Fife’s lost mines and the flood of Longannet