Dundee found itself in the grip of the Aids epidemic 35 years ago which sparked fear, confusion and prejudice in the city.

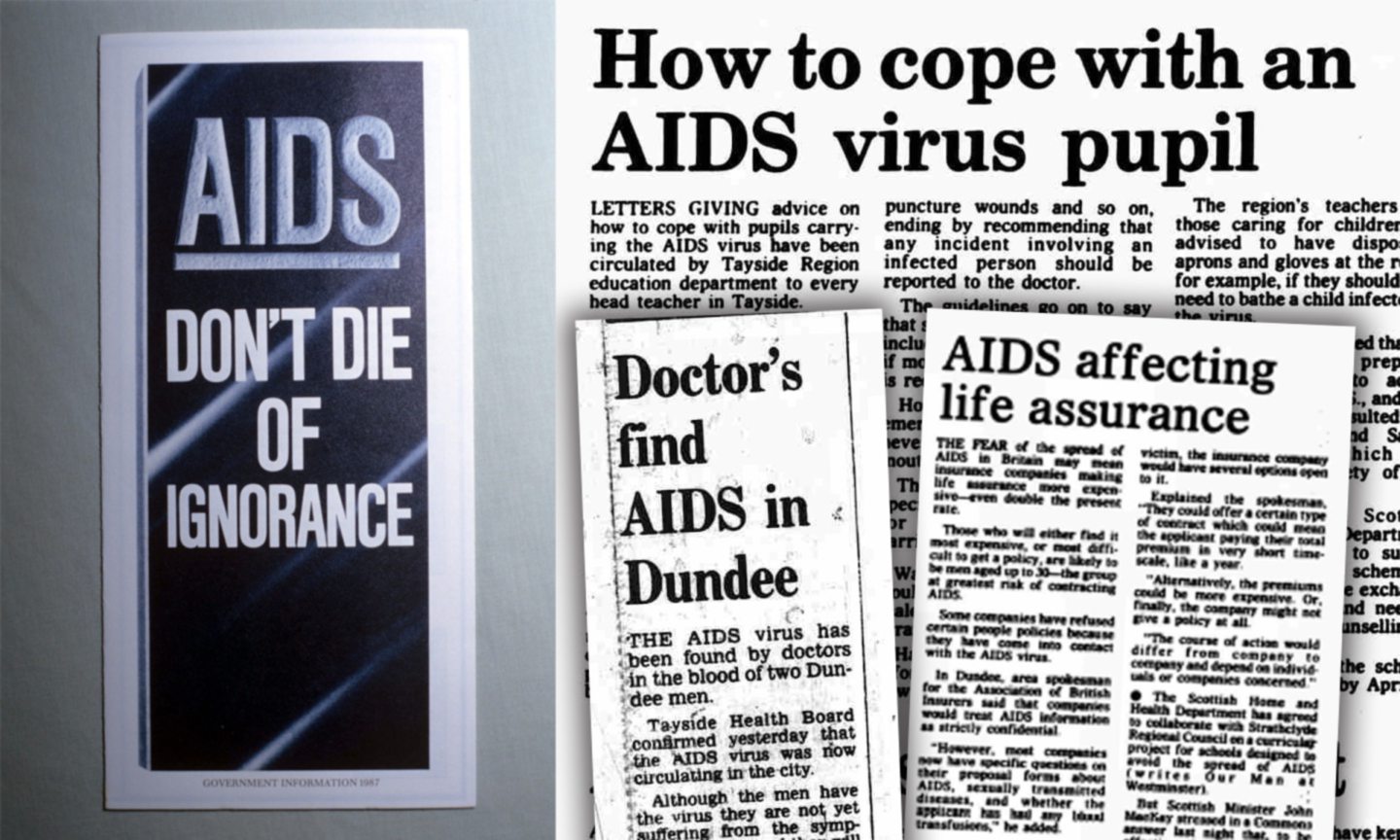

Aids first came to public attention in the UK in 1982 and was followed by a widespread media campaign warning the public of the need for “safer sex”.

There was no known effective treatment at the time.

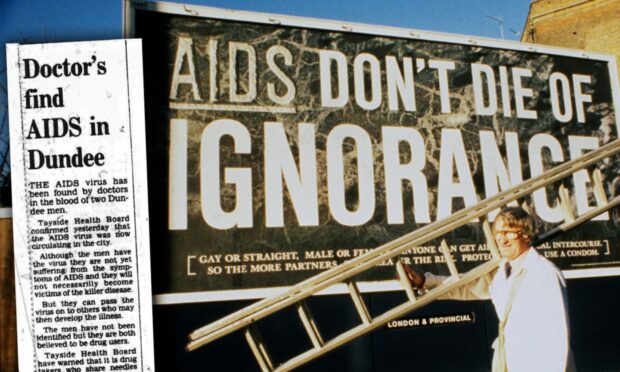

The first newspaper reports emerged in 1985 that the HIV virus had been identified in Dundee when two men tested positive who were drug users.

Tayside Health Board confirmed the virus was circulating in the city and warned that drug takers who share needles and their sexual partners were at greatest risk.

One newspaper article described how special arrangements were introduced for screening “Aids suspects” at the request of their own doctor.

The virus spread with alarming speed and there were 128 people diagnosed with HIV in Tayside by November 1986, although the actual figure was much higher.

At least 50 people in the region were now dead, while over the River Tay, a Dunfermline couple’s baby was reported to be the first born in Scotland with the Aids virus.

But whilst uninformed prejudices saw the virus branded a “gay disease”, the majority of infections (more than half) were observed in people who used intravenous drugs.

A Courier article in 1986 suggested Dundee in terms of cases per capita was now on a par with Edinburgh, which had already become known as the Aids capital of Europe.

Police, health experts and local authority officials then set up a working group in Dundee to help combat what was described as “the growing menace of Aids in the city”.

Fear and panic in the city

Dundee, back then, was awash with heroin in the 1980s and the city had one of the highest levels of HIV infection among injecting drug users.

Some were stealing to fund their drug use and police went public when a man with Aids cut himself during a house break-in and blood was found on a broken window.

A senior detective warned that where blood and broken glass was discovered in such circumstances it should be treated “with the utmost caution”.

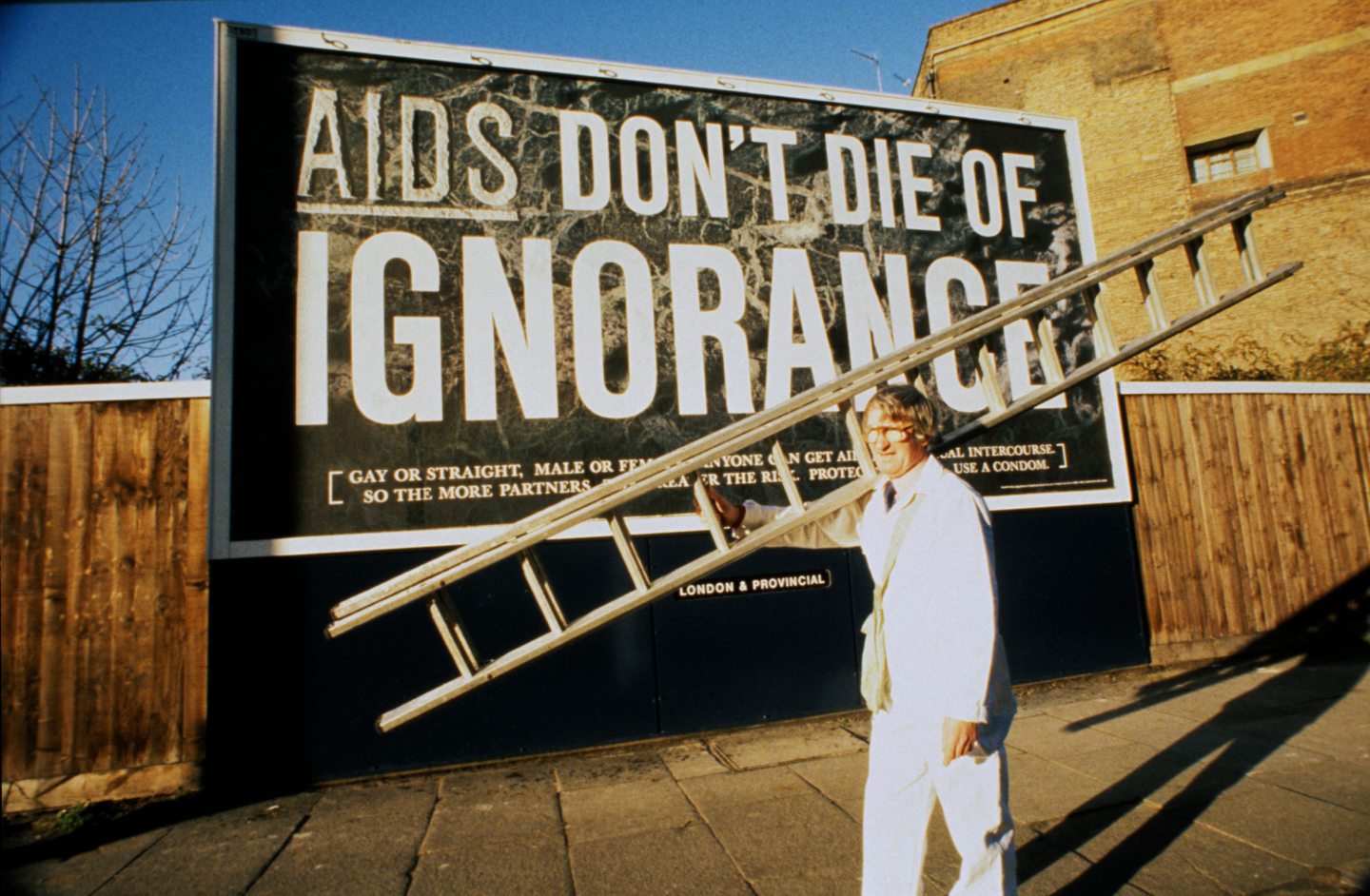

The UK Government would ramp up the fear factor further.

That’s when a leaflet was sent to every household in the country and the now notorious TV adverts were screened featuring tombstones and a grim reaper.

Some said the advert was so scary it put a whole generation off having sex.

In 1987 every head teacher was given a letter from Tayside’s education department giving advice on “how to cope with pupils carrying the Aids virus”.

Special measures included the use of a mouthpiece for mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Teachers were reminded in the guidelines that emergency resuscitation for pupils living with Aids “should never be withheld” even if no mouthpiece was available.

Teachers and those caring for children were advised to have disposable aprons and gloves at the ready “if they should ever need to bathe a child infected by the virus”.

This was someone’s daughter, someone’s son.

The guidance issued to staff provided advice on “hygiene measures recommended by all educational establishments” and covered “personal hygiene, spillages of body fluids, spitting, cuts and puncture wounds” and ended by recommending that “any incident involving an infected person should be reported to the doctor”.

Waste contaminated by blood would have to be collected into sealed bags with the council arranging for incineration at specialist disposal sites.

Were people with HIV now being portrayed as walking biological weapons?

The fear of Aids also had consequences for life insurance in 1987.

Men aged 18-30, described as “the group at greatest risk of contracting Aids” were being warned they would “find it more expensive or more difficult to get a policy”.

A spokesman for the Association of British Insurers in Dundee broke it down further following a discussion with The Courier about the possible impact.

He said that companies “would treat Aids information as strictly confidential”.

“However, most companies now have specific questions on their proposal forms about Aids, sexually transmitted diseases and whether the applicant has had any blood transfusions,” he said.

“Following a possible doctor’s report, should the applicant be found to be either a carrier or a victim, the insurance company would have several options open to it.

“They could offer a certain type of contract which could mean the applicant paying their total premium in very short timescale, like a year.

“Alternatively, the premiums could be more expensive. Or, finally, the company might not give a policy at all.

“The course of action would differ from company to company and depend on individuals or companies concerned.”

Dedicated ward set up to treat patients

A weekly table of Aids and HIV figures started being published in a similar way to what was seen at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic between 2020-2022.

They were broken down by categories which included tallies for “HIV positive needle-sharing intravenous drug users”, “heterosexual cases” and “homosexual cases”.

A needle exchange for drug addicts opened in Dundee in 1988 before a £260,000 unit at King’s Cross Hospital for “Aids and HIV-infected patients” opened in 1989.

HIV was almost lethal in those days.

So many young people faded away gradually in the dedicated ward.

However, some deteriorated more suddenly and died.

The staff who cared for these patients still remember so clearly the faces of those who died.

Some remain haunted by those days.

They were the lucky ones.

Researchers toured the city from June 1994 to March 1995, taking saliva samples from more than 200 known drug injectors, and found more than 26% had HIV.

Bedside sit-in protest by proud father

But lack of funds saw the specialist unit marked for closure in 1996, a move that saw the father of a Dundee woman dying of Aids threaten to chain himself to her hospital bed.

John Gellatly sat with a length of stout chain and two padlocks by the bedside of daughter Tracey who was the only remaining patient in ward one.

Tracey was 27 and was diagnosed with HIV in 1986.

She had spent over six years on and off in the ward but had been given just a matter of weeks to live when the closure announcement was made public.

Her wish was to die in the ward that had been her “home” and health bosses thankfully shelved plans to transfer her following the bedside sit-in protest by her father.

A small team of nurses cared for Tracey until she died peacefully in June 1996 but there was no reprieve for the ward which was closed to new admissions.

John spent a month by his daughter’s side and left the ward when she died.

“Tracey and I discussed this shortly before she died and it was her wish that, after her death, I shouldn’t continue to fight what we both agreed had become a lost cause.”

He said the care given to Tracey by nurses in ward one had been “second to none”.

Since the discovery of HIV and Aids in the early 1980s a substantial number of advances have been made in its treatment.

The virus, and its subsequent evolution into Aids when in the immune system, was once seen as a death sentence.

However, treatments today are so advanced that HIV is now a “very treatable and manageable infection” and people can live with the disease to old age.

The fight against the virus isn’t over but thankfully the vast majority of attitudes towards Aids no longer remain stuck in the 1980s.

More like this:

Social distancing and the ‘stay home’ message was slightly different in Dundee 500 years ago

Conversation