One couldn’t have imagined that an ancient block of red sandstone would become such a symbolic part of life in the modern British constitution.

But there again, the Stone of Destiny, which was the subject of an infamous heist by a quartet of students on Christmas Day in 1950, has been used for centuries in the coronation of the monarchs of Scotland and dates back more than 200 years to before the Battle of Hastings or the Bayeux Tapestry was created.

From then on, it has been used in the coronation ceremonies of English monarchs.

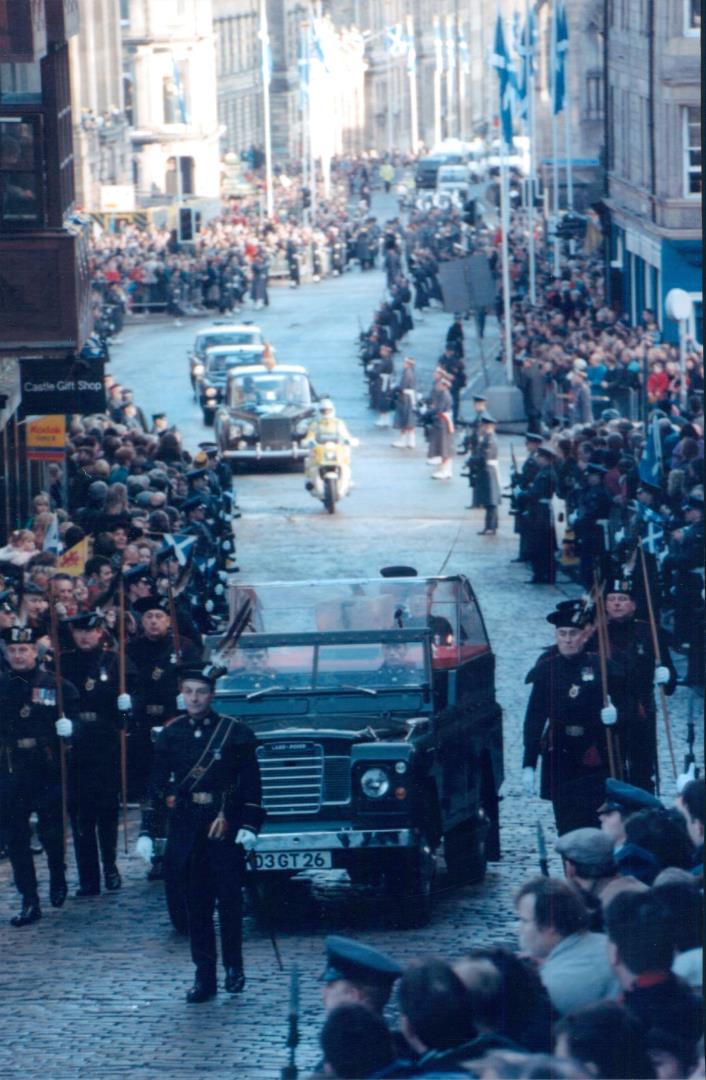

In 1996, the British Government decided to return the stone to Scotland, when it was not in use at coronations, and the precious relic was transported to Edinburgh Castle, where it is currently kept safely stored along the Scottish Crown Jewels.

Yet, of course, following the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the artefact has once more resurfaced in the public gaze and although the former Prince Charles became King on Thursday September 8, it remains the tradition to leave a sufficient amount of time for mourning before a new monarch is formally crowned.

A date for the latter event has not yet been announced officially, but some sources have reported that the coronation is likely to be in “spring or summer of next year”.

In keeping with coronation traditions, the Stone of Destiny will leave Scotland once more and travel to Westminster Abbey for the crowning of King Charles III.

If that happens, then there could be the prospect of renewed argument, in what has become a febrile political climate, about how long the stone should stay in England or even whether it should be removed at all.

Stone of Destiny – Life and times

Historically, the artefact was kept at the now-ruined Scone Abbey in Scone, after it was brought there from Iona by Kenneth MacAlpin around 841 AD.

However, it was seized by Edward I’s forces from Scone during the English invasion of Scotland in 1296, and was used in the coronation of the monarchs of England as well as the monarchs of Great Britain and the United Kingdom, following the Treaty of Union of 1707.

Yet, not everybody agrees that it should have a dual link to both countries, given its original use as a potent piece of Scottish heritage for hundreds of years.

The stone was most recently used in 1953 for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, but, prior to that ceremony, the item became the focus of headlines after it was removed from Westminster Abbey.

The theft of the Stone of Destiny

The theft of the Stone of Destiny during the Yuletide 72 years ago forced the closure of the border between Scotland and England for the first time in 400 years.

Frantic checks were carried out on myriad hotels and boarding houses on both sides of the Cheviots as the authorities responded to criticism of their lack of security in the first place to find the whereabouts of the historic relic and the identity of the perpetrators.

Eventually, it transpired the unlikely band of self-styled patriots comprised 22-year-old domestic science teacher Kay Matheson, 25-year-old Glasgow University law student Ian Hamilton and two of his fellow students, Alan Stuart and Gavin Vernon.

The theft, which was like something from an Ealing comedy, sparked a nationwide cat-and-mouse hunt, with the quartet evading the authorities for several months.

Many people in Scotland felt a thrill of pride at the audacity of the night raiders, but the establishment deplored the incident and questions were asked in Parliament about the manner in which a student prank had left so many dignitaries with red faces.

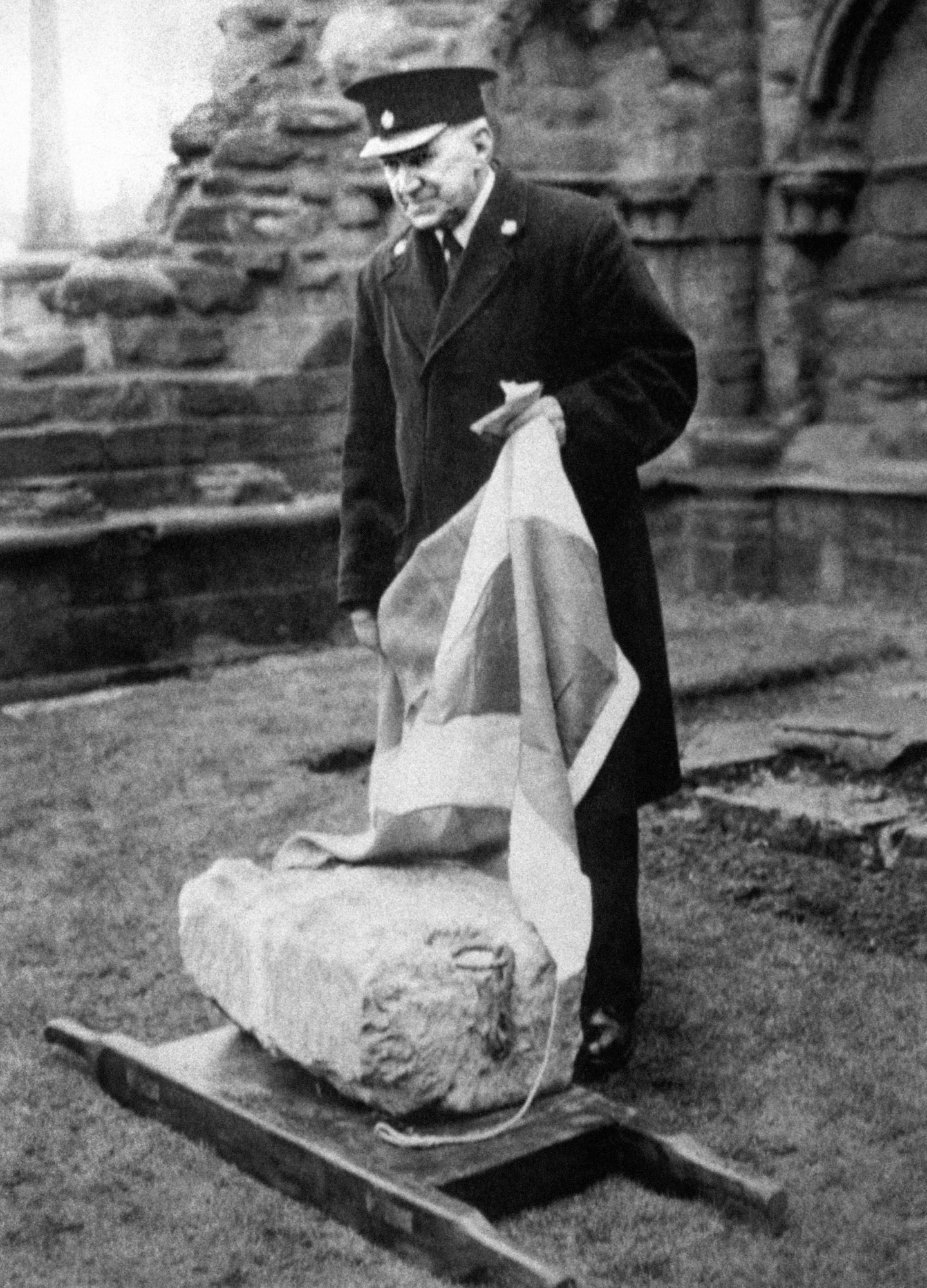

But, thereafter, the stone was stored in a variety of locations due to the intensifying police search, before the group eventually placed it on the altar in the symbolic location of Arbroath Abbey, draped in a Saltire….which was manna from heaven for the tabloid newspapers and supporters of the nascent Scottish National Party.

It was left by those that had been hiding it on the altar of Arbroath Abbey on April 11 1951. Once the London police had been informed of its whereabouts, the stone was returned to Westminster four months after it had been removed.

Yet, it was typical of the political storm brewing behind the scenes that rumours soon began circulating that a carbon copy had been fashioned of the stone, and that the artefact which was returned to London was not the original version.

Stone of Destiny return to Scotland

The whole thing was an audacious escapade, one which generated prodigious amounts of international newspaper coverage and James Chuter Ede, the Home Secretary of the time, stated it wasn’t in the public interest to prosecute the students.

It was, according to many people, a victimless crime and, unsurprisingly, there have been several films and programmes about the theft, most famously the 2008 Canadian-Scots feature, Stone of Destiny, starring Charlie Cox and Robert Carlyle.

More than a decade earlier, on St Andrew’s Day 1996, the stone was returned to Scotland on the understanding that it could be “borrowed” for any coronations at Westminster.

Which will bring it back into the spotlight in the coming months.

Stone of Destiny to be used during King Charles III coronation

Historic Environment Scotland, the organisation which manages Edinburgh Castle, announced, in the wake of the Queen’s death, that the stone would be used in King Charles III’s coronation before it was returned to the castle’s Crown Room.

HES said on September 12: “The stone will only leave Scotland again for a coronation in Westminster Abbey.”

But there have been no further details of when and how and for how long this coarse-grained, pinkish buff sandstone, will be conveyed from Edinburgh 500 miles south.

And doubtless, when anything has been clarified, it will spark renewed argument on both sides of the independence debate.

Not bad for an item which David Dickinson might have described as being “cheap as chips” on an antiques show.

But there again, it dates back nearly 1,300 years.

Or does it?

More like this:

Was the real Stone of Destiny hidden in plain sight in Dundee?

The King of Whitfield: How Charles won hearts of residents in Dundee estate