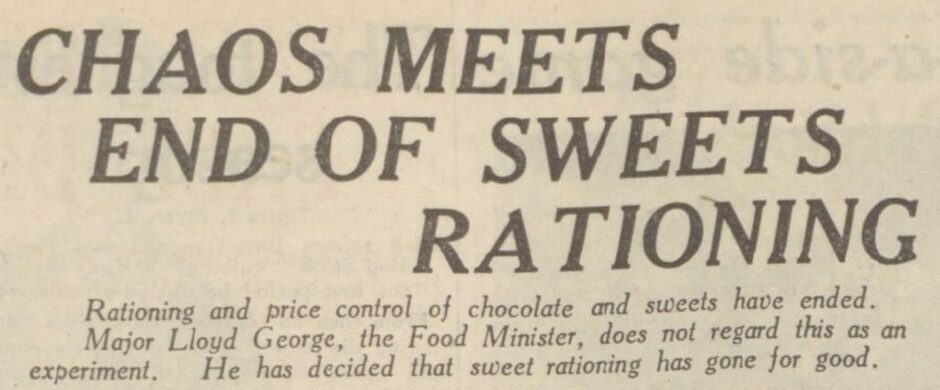

There was “surprise and delight” as well as “confusion and chaos” when sweet rationing finally ended in Dundee 70 years ago.

As restrictions lifted, Dundonians flocked to city sweetie shops, hoping to get their sugar fix – only to find some wouldn’t hand over the gooey goods.

Confectioners had received mixed messages regarding the end of rationing, which after weeks of speculation, was announced out of the blue in the press on February 4.

But it was several days before many sweetie shops received the official notification from the Ministry of Food, which oversaw rationing.

Food rationing was introduced across Britain in 1940, to ensure fair shares for everyone amid dwindling supplies during the Second World War.

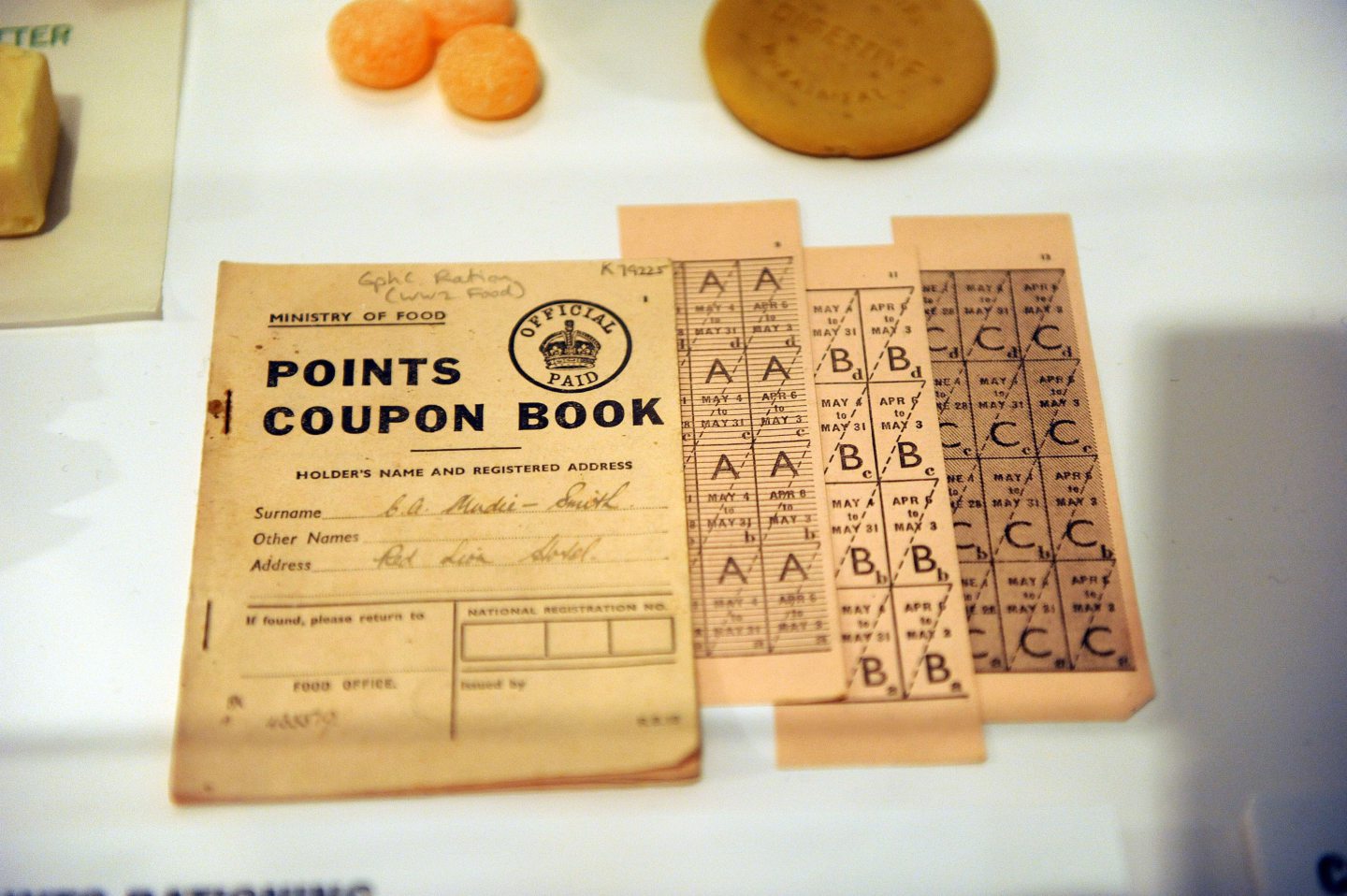

Each man, woman and child was issued with a ration book containing coupons to be used when purchasing items like sugar, meat, cheese and fats.

But as the war continued, more items were put on ration, including sugar and chocolate, which were restricted in July 1942.

Each person over the age of five was allowed only 2oz (57g) of sweets a week, due to the scarcity of imported raw ingredients like cocoa and sugar.

By then, fruit, vegetables and fish were about the only foodstuffs not to be rationed, and fruits, such as bananas, was a rarity.

Traditional sweets were wartime favourite

As if the war wasn’t miserable enough, Cadbury was forced to withdraw production of its Dairy Milk chocolate, because the Ministry of Food banned manufacturers from using fresh milk in 1941.

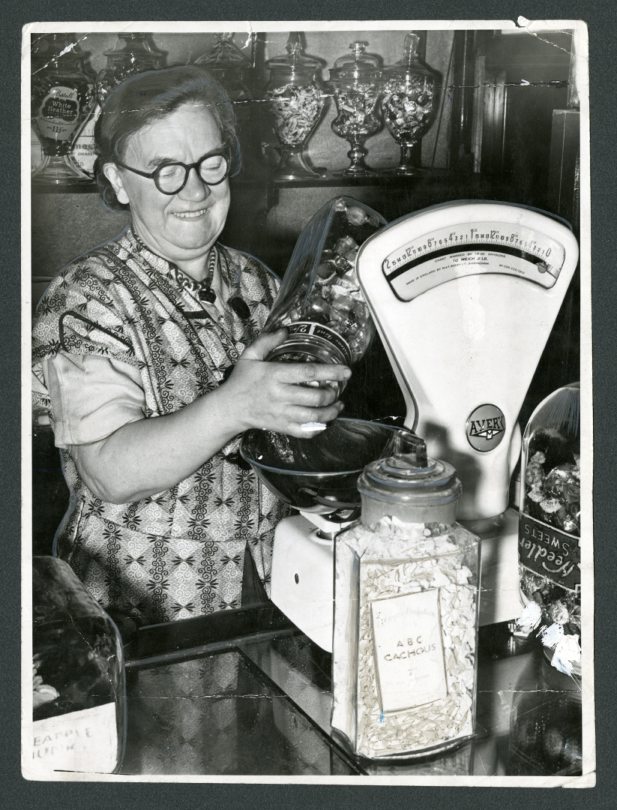

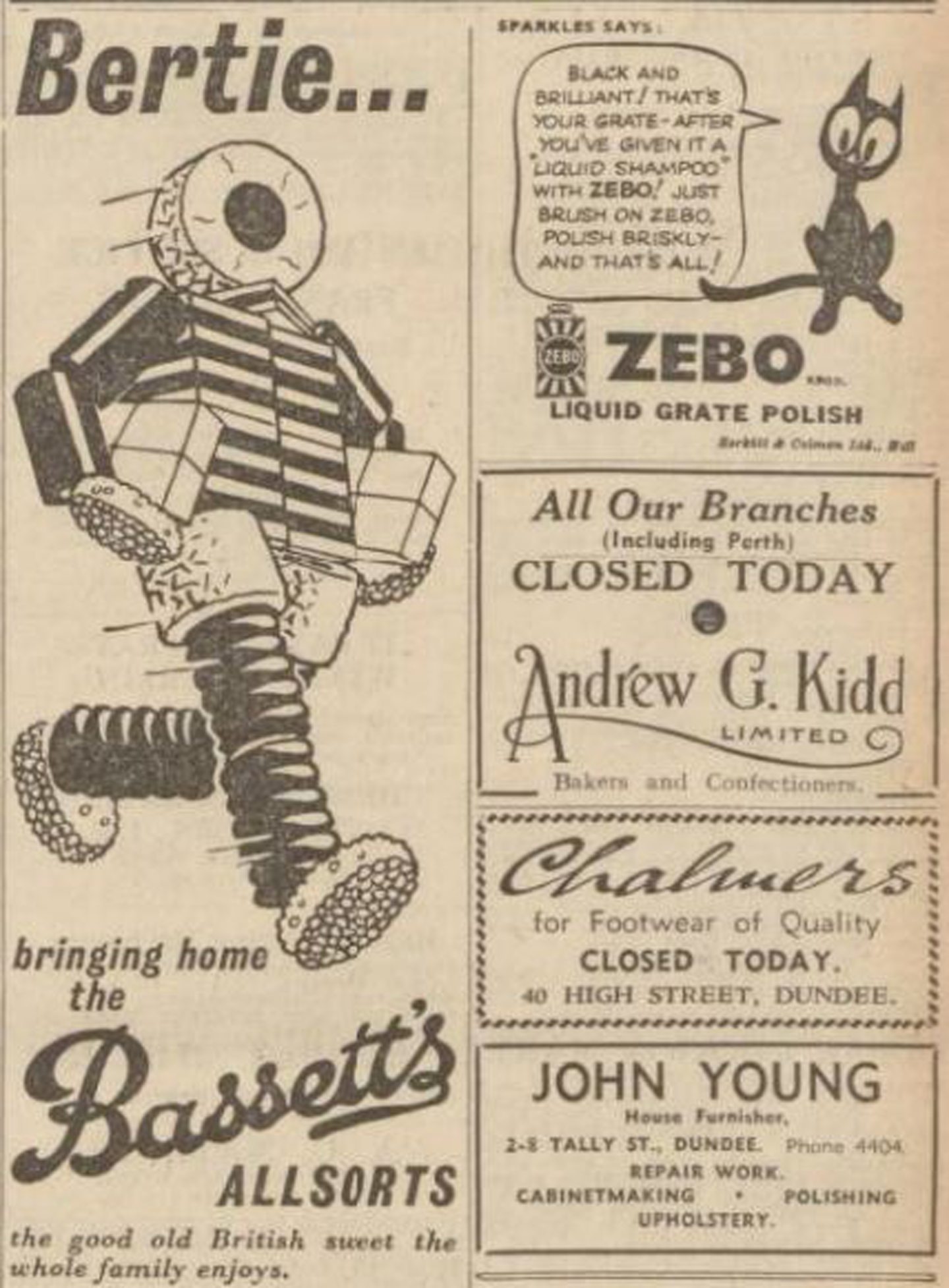

As ‘ration chocolate’ failed to hit the sweet spot with punters, it was the traditional sweetie shop treats that most children saved their precious pocket money and coupons for.

Boiled sweets, pear drops, cola cubes and toffee had fewer ingredients – and many could be made in the shopkeeper’s own premises.

There was jubilation when sweet rationing initially ended in April 1949, but it was short-lived as a sugar rush depleted supplies.

Confectionery went back on ration just four months later, when production became unsustainable to meet the demand of the British public’s insatiable sweet tooth.

In fact, some Dundee retailers had to impose unofficial rationing schemes during the ‘off-ration’ period to maintain stock levels.

‘Derationing’ began in 1948, but it was February 1953 before sweet rationing finally met its sticky end – nearly eight long years after the war ended.

Shortly after Food Minister Gwilyn Lloyd George announced the end of rationing, a Courier reporter took to the sweet shops of Dundee to investigate further.

It was a hard job, but someone had to do it.

In the first shop, the assistant wouldn’t sell sweets without a ration coupon, but the second and third outlets proved more fruitful, handing over the sweets.

A fourth shop had a sign in the window stating they wouldn’t sell confectionery without coupons.

Many other sweet shops were closed for the half-day holiday, but those open spoke of chaotic scenes as they were overrun with keen customers.

One manageress told The Courier: “We’ve been invaded. They are all demanding sweets off the ration.”

Confused, she phoned the food office only to be told it wasn’t yet ‘official’ and that she should continue to take coupons.

Public warned not to ‘lose their heads’

The derationing news even came as a surprise to Dundee’s confectionery manufacturers.

Mr Eadie, secretary of Dundee and Perth branch National Union of Retail Confectioners, said the news was “incredible”.

He added that the branch’s annual meeting was held just two days previously and they “had no inkling of derationing”.

He explained that “supplies had certainly improved slightly, and if the public were reasonable in their demand, and didn’t lose their heads and hoard like the last time, retailers would get by all right”.

Mr Baillie of the Tay Confectionery Company, meanwhile, said the news was “very welcome”.

But not everyone was as thrilled.

One Dundee housewife wrote to The Courier letters page a few days later and said: “I have two children who are both very fond of sugar (in tea, sprinkled on puddings and porridge, etc), as a result of which I never have any left for baking or jam making.

“I think it would have been a much wiser move on the part of the Government to have taken sugar off the ration, or at least increased it.

“The housewife cannot afford to buy sweets ad lib, but with sugar off the ration it would have helped us to save on such expensive items as cakes, jams, etc.”

Another reader wrote back rather bluntly and said: “I was always taught that a good Scot does not take sugar in porridge, and my children do not take it either.”

Conversation