As far as press coverage of the current pandemic situation is concerned, the old saying “You pays your money and you takes your choice” has never been more accurate.

While the Metro warns that “Lockdowns are failing” and the Daily Mail prints pictures of Boris Johnson and his top scientific advisers, asking “When will they listen?”, the Daily Express urges “We have to stick with it”.

For every possible opinion on government policy, there’s a newspaper headline for it. And that’s before we add in the Scottish and local press and the different lockdown policies in different parts of the country.

And surely this is a good thing? A functioning democracy needs a critical press that questions and holds government to account.

The 19th Century ideal that journalists should act as a fourth estate, holding those in power to account, still holds a powerful draw for new students on our journalism courses at RGU.

It’s interesting, too, to see that, on this subject, newspapers are not necessarily holding to party lines. Many of the more aggressive attacks on Johnson, in particular, are coming from the right-wing press, such as the Daily Mail.

However, as all these news stories and opinion pieces go into circulation on social media, they add to the extreme noise that now constantly surrounds us.

While social media allows wide dissemination of news, government policy and opinion, it also amplifies misinformation and gives it equal status with truth.

There are also well-founded concerns that current levels of information are producing an ‘infodemic’, which makes it difficult for members of the public to identify the most reliable information, particularly as rules about lockdown become more complex.

And this is where the problem lies – if there are so many possible reactions to new lockdown policies, does this make it easier for us to dismiss the ones that we don’t personally agree with?

Concerns about fake news about Covid-19 circulating via social media have been highlighted by academics and governments across the globe.

Indeed, the director of the World Health Organization remarked that misinformation about the coronavirus might be the most contagious thing about it.

In April, the CoronaVirusFacts Alliance database recorded nearly 4,000 coronavirus-related hoaxes circulating globally.

While in the UK, an Ofcom study suggested that 46% of internet-using adults saw false or misleading information about the virus in the first week of the country’s lockdown.

In recent weeks, scientists have spoken out about the pressures they have felt from social-media attacks, which have impacted on open scholarly debate about scientific approaches to the pandemic.

On the more positive side, social media has allowed humour to creep into the nation’s conversation.

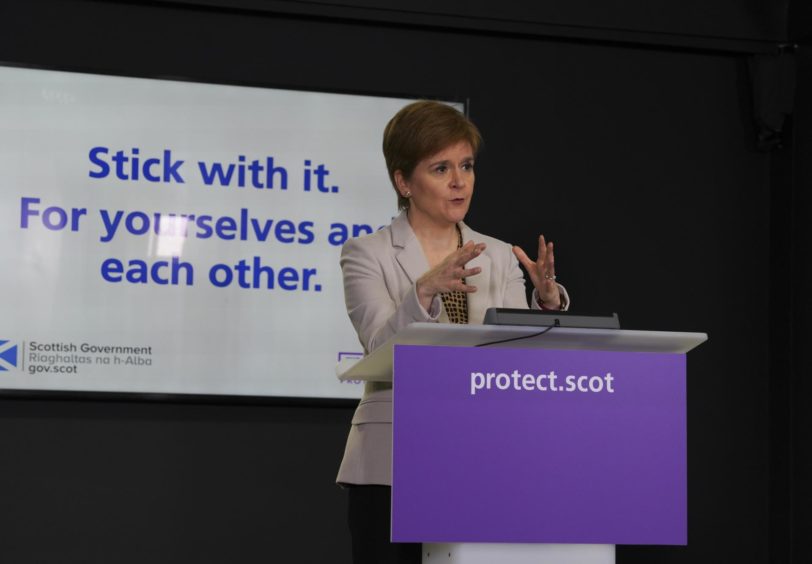

Sometimes this has helped governments’ messages, such as Janey Godley’s voice-overs of Nicola Sturgeon’s briefings, which have served to reinforce the first minister’s warnings while also producing a slightly different persona for Sturgeon.

At other times, however, satirical takes on the news have undermined government policy, such as the many memes referencing Barnard Castle and eye tests after Dominic Cummings travelled north during lockdown.

What is particularly interesting about lockdown for a media scholar is the impact it has had on our use of and trust in mainstream media.

Research in the US, and some of the research we are undertaking at RGU, suggests that lockdown has led to somewhat of a return to reliance on legacy media such as radio and television news and newspapers.

Radio listening boomed during early lockdown as listeners tuned in for the latest news, but also for companionship and entertainment.

Television news likewise saw audience numbers rise, with BBC news, for example, reaching an audience of more than 20 million a week across its evening news bulletins in March.

The BBC’s news website also broke records, with its most popular video explaining coronavirus being watched more than 50 million times that month.

However, the story is not as simple as the public realising the worth of mainstream media, forsaking social media, and returning to their old habits.

Instead, we now have a much more complex picture of hybrid media use. We are accessing and sharing clips from BBC news or stories on newspaper websites via social media such as Twitter and Facebook.

Thus clips from news television programmes or articles from mainstream newspapers are presented to us within different framings, sometimes positive but sometimes negative, depending on the comments attached by different posters.

We might see the news and opinion we are accessing via social media as a kind of palimpsest – a piece of writing that has been over-written and altered by the writings of others that have accrued over time.

And because of the way in which social media allows us to syphon away information and opinion that is contrary to our own beliefs, we tend to access news articles that support our own opinion on subjects such as mask-wearing or holidays abroad.

How can any government cut through all this noise to make new policy clear and ensure public compliance, if not agreement?

Governments govern by the consent of the people, but it is hard to achieve that consent when you can’t be heard above a rising noise of disagreement and confusion.

Sarah Pedersen is professor of communication and media at Robert Gordon University. Her new book, The Politicization of Mumsnet, is published October 15.