Jim McLean came closer than any manager Scotland has produced to solving the greatest problem in football — how to face teams with better players than yours and work out a way to beat them.

It’s a puzzle faced by many managers.

Jim’s classic Dundee United teams had stars, of course. David Narey is the best footballer the City of Discovery ever discovered. Paul Sturrock, with his ability to twist to a new angle of attack, had a unique talent for opening defences. Ralph Milne (when in the mood) was almost unstoppable. Maurice Malpas had a football intelligence that grew and grew.

But Jim also had lesser lights. The likes of John Holt, Billy Kirkwood and Derek Stark. Their feats are rarely mentioned but they deserve more plaudits than they usually get, because they had a talent that is rarely talked about. They kept United’s shape and executed instructions to the letter. They were the foundations upon which game plans were built.

The real work of putting a playing system in place is done on the training ground. A plan has to be worked upon. It takes months to walk a team through all possible on-field scenarios until they think as one. In any transition of play, every player has to recognise exactly what is about to happen, and know their role.

The groundwork, according to former United man Allan Preston, was laid from the start of each player’s time with the club.

“Jim’s training was basically the same for kids as for the first team,” he said.

“We were being prepared to slot in to a method of playing that would make us instantly useful, instantly able to understand team orders. It’s the way Barcelona’s La Masia academy does things nowadays.”

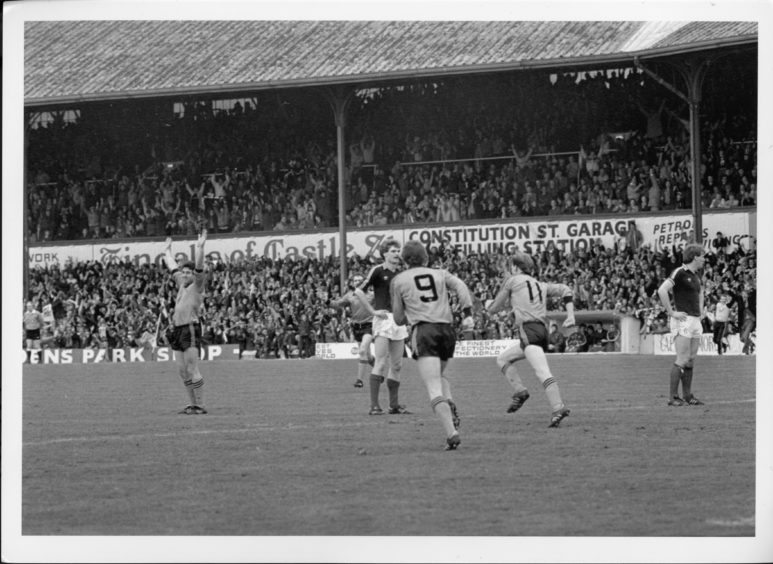

Take one of the most famous goals in United’s history. Milne’s chip on May 14, 1983. Every Arab remembers the sublime finish. But that solo brilliance was made possible by a rehearsed move.

It starts when Malpas, at left-back, wins a header. The ball is knocked down to Dave Narey, who takes two touches to play it to Paul Sturrock. Luggy controls, moves the ball a couple of yards, then plays in Milne, who has four touches before the chip. It takes 14 seconds from Malpas’s header to the ball hitting the net, during which time three United players have controlled possession and the ball travels 80 yards.

It is a classic counter-attack. But the remarkable thing is what goes on in other parts of the pitch.

As soon as Sturrock plays the ball forward, Davie Dodds makes a run from centre-forward to the inside-left channel, taking a defender with him. Kirkwood makes a lung-busting run from central midfield to inside-right, also taking away a defender. Milne uses the space these runs have opened to advance 20 yards down the centre of the field without a defender coming towards him. He has all the time needed to set himself for the delicate chip.

That attack, prising open the centre of a defence, is the result of hours on a training pitch and requires crucial input by players who don’t touch the ball. The aim is to create space, then utilise that space. Dodds and Kirkwood have vital assists in that goal.

From the same game, Narey wins a penalty from a move so obviously rehearsed you can see Eamonn Bannon waiting to take the throw-in until the team shuffles themselves backwards and forwards to their “start points”. The throw looks like it is intended for Sturrock, but is into the path of Narey, who is fouled.

Two rehearsed moves, two goals, game (and championship) won. But the hard work was done weeks previously.

McLean’s teams played a counter-attacking game of a type that is becoming rare in football. Nowadays, in pale imitation of Guardiola’s Barcelona, almost every team and almost every move starts with the ball played across the back four, sideways, and sideways again. Football had more forward passes in the 1980s.

But Jim wasn’t looking for gung-ho attack, neither was he advocating route-one football. The general structure was that a back four was maintained at all times, but a lot of running was required for midfielders and forwards to open themselves for passes, or open spaces for others. The secret is good movement. The players had to recognise when the forward pass was “on”.

United would line up as a 4-4-2, sometimes a 4-5-1, when defending, which quickly switched to a 4-3-3 or even a 4-2-4 when they got the ball.

The first goal against Roma in the 1984 European Cup semi-final is a close-range Dodds strike. But, again, the move has to be examined.

Richard Gough, playing full-back, puts in a cross, which reaches Bannon, who has a shot. The keeper parries, a defender has a sclaff at it, then Sturrock plays in Dodds to slam it in — a scrambled goal in a crowded box.

The significant thing, though, is that there are four United attackers within eight yards of goal when Gough’s cross comes in, and Kirkwood on the edge of the box. If Gough, advanced on the right, is counted, that’s six players in attacking positions.

Again, it is a counter attack at speed, and in numbers. It isn’t, in truth, as pretty as the Dens Park goal but a great reward is won from a clear intention to get numbers in the box for crosses.

There is a risk involved in committing such numbers forward, especially (as in that Roma game) when playing a team full of internationalists. The danger is leaving yourself exposed at the back.

But Jim had a plan for that too.

He had studied the famous Catenaccio system that was still prevalent in Italian football. The word catenaccio means “door bolt” and the essence is four defenders with a sweeper (the bolt) behind. It was designed to provide in-depth defence and nullify the effect of runs down the channels. The greatest manager of the art was Helenio Herrera, with his “Grande Inter” side of the 1960s. Herrera’s influence lingered in Serie A for decades.

To counter this, Jim instructed his players to “press” the Romans high up the pitch. But not only were they to press, they were asked to do it the instant they lost the ball. As well as counter-attacking, United were counter-pressing. Nowadays this has a fancy name – “gegenpressing”. The rough English translation of the German word “gegen” is “counter”. Jurgen Klopp’s Dortmund side in the early 2010s labeled their gegenpressing “heavy metal football”. Jim, a Sinatra fan, did it his way fully 30 years before.

An overload of players is the one thing most likely to work against a sweeper system. Catenaccio is designed to have at least one more defender than there are attackers. Crowding the defence results in chances, and that’s what allowed Doddsie the shot against Roma.

Paul Sturrock, who was more often than not involved at the top end of the park, explains: “Jim insisted I learn to play on the wing as well as through the middle and it made my career. It kept teams guessing as to what I was going to do and it’s why I achieved what I did as a player.”

The way Jim’s United teams used full-backs in counter-attacks was also innovative. One ploy was to have full-backs surge forward through the inside-right or left channels, not the wing. Again in the Roma game, Derek Stark powers forward in this way to get in his long-range strike for the second goal.

In the most famous of United teams, Maurice Malpas on the left was less likely than Richard Gough on the right to get forward. One of the reasons for this was Gough’s ability in the air.

At Old Trafford in 1984, Jim’s ploy was for long diagonals to find Gough around the corner of the 18-yard box. Manchester United manager Ron Atkinson hadn’t studied how the wee Scottish team played and left the diminutive Jesper Olsen to track back with Gough, and even mark him at set-pieces

McLean, however, had certainly done his homework. United’s first equaliser, by Paul Hegarty, is a direct result of Gough getting his head to a free kick and playing it across the box.

Two things strike you if you watch 1980s footage of United. The first is how often you see a direct brand of football almost lost to the modern game, with Bannon, Sturrock or Milne taking on a man in wide areas to get crosses in. The second is how many goals United score from corners, free-kicks and throw-ins.

The 1980 League Cup Final is a 3-0 United win over Dundee, every goal a header from a set-piece.

Sturrock receives a throw-in for the first, twists, turns, and gets in a cross from which Dodds scores. It is clear Dodds knows exactly when to make his run, the bemused defence are spectators. The second and third are almost identical. Both are from Graeme Payne corners, which Hegarty’s aerial prowess sends goalwards, and Sturrock knocks in rebounds. On both occasions the corner is flighted to almost exactly the same place. The United players knew what was happening, and roughly where Heggie would knock the ball on to.

Indeed, there has rarely been a better team than Jim’s early-80s line-up for creating chances from throw-ins, another disappearing art. One move they tried time after time involved Milne coming almost to the toes of the thrower, followed by Sturrock 10 yards behind. Milne wouldn’t get the ball, but would turn and speed back into the box, close by the side of the oncoming Sturrock. Luggy received the throw, laid it off into the path of Milne, who was “in” for a shot. Kevin Gallacher’s goal against Barcelona is a variation, actually a slightly botched version, of this.

McLean was fulfilling the description given to him time after time, of “being ahead of his time”. This was apparent in his use of specialist training methods, psychological preparation, and dietary regimes. But most telling of all was his adoption of innovative tactics to win games a corner shop team shouldn’t have won.

It is impossible to know, of course, how Jim’s tactics would fare in these post-tiki-taka days of teams retaining possession at all costs. He did, it is true, always want his players to keep the ball. But Jim wanted to win games, not come top in the possession stats.

The nuts and bolts of another currently fashionable idea would be familiar to Jim. The idea of “transitions”.

Today’s tacticians describe the game as four phases:

1. Possession.

2. Not having possession.

3. Immediately after losing possession.

4. Immediately after winning possession.

These are the points where players have to quickly transition from doing one thing to doing another, from being in one place on the pitch to being in another.

United’s greatest result under McLean was probably beating Barcelona in the Nou Camp. The best attacking performance was humbling AS Monaco 5-2. The best defensive display was the 1-1 draw at Werder Bremen. But the best European performance, from start to finish, was thrashing Standard Liege 4-0 in 1983.

The first goal, especially, is a good example of handling transitions. For that goal, Eamonn Bannon doesn’t look like getting on the end of a dink down the left, but wins the ball with a sliding tackle. The actions of the other players in the transition from not having possession to immediately after gaining possession finds Bannon with three targets rushing into the box for his cross. Milne scores. The players knew exactly what to do the instant Bannon regained possession.

For the second, the Liege defence is pushing out, while United appear to be going backwards with the ball. The United strikers go with the defence. But then, rapidly, the emphasis switches. Milne times a run from outside to inside to beat the offside trap and finishes with a deft chip. The transition from going backwards to going forwards requires precision, and again looks simple. But McLean would have studied the Liege offside trap and drilled his players in not just how to beat it, but (and this is the crucial bit) when to beat it. They all had to put this trap-springing idea into practice at exactly the same time.

United were in control for every minute of that game. In attack, in defence, every transition, in every area of the pitch. Rarely, if ever, has a Scottish team played so well in a European tie. It doesn’t earn much respect throughout the rest of Scotland, because it was done in Dundee not Glasgow. But it should be studied by anyone interested in what teamwork looks like. United comprehensively outplayed a continental team by being better at continental football than they were.

In the words of McLean’s former assistant, Walter Smith: “Historically, Jim might not have achieved the acclaim he merited, taking a Scottish provincial club to the semi-final of the European Cup.”

Tactics constantly evolve — from “WM” 2-3-5 formations, to route-one, to false nines, to teams so desperate to retain possession they work corners back to their goalkeepers. There are names we all respect — Guszstav Sebes who astonished the world with his Mighty Magyars in the 1950s, Rinus Michels who invented total football in the 1970s.

Dundee United had just such an original thinker, a man who worked out how to win when the odds were stacked against him. Jim McLean is one of the greatest football brains Scotland ever produced.

Jim McLean Dundee United Legend is on sale now, £15.99, free P&P, from dcthomsonshop.co.uk