New words and phrases enter the sporting lexicon all the time, and the media can’t help but reflect this.

This season in round-ball football, the two new phrases that seem to have sprung up in common usage are probably VAR (football being football, it can’t be having rugby’s TMO and cricket’s DRS, they have their own special acronym) and specific to Scotland recently, “strict liability”.

No, this is simply not the place to go into that particular minefield, thanks very much.

Rugby seems to get a new stock phrase every year. It used to be harmless, largely meaningless things like “line-speed”. But the phrase I’ve grown familiar with this year more than any other is much more sinister: “symptom-free”.

In one respect we should be happy, overuse of the common phrase to mark a player’s recovery from concussion should be an indication of the seriousness with the condition is now treated in the game.

However it has exposed the complacency – mostly based on ignorance – which infected the game. Only now do we discover that we have been endangering the future good health of young men across decades.

There’s a test case about to hit the courts in France that is going to send shockwaves through the sport if it is successful. Former Canadian international lock Jamie Cudmore won the right in January to continue his lawsuit against Clermont-Auvergne alleging the club made him play on despite suffering a concussion in the 2015 Heineken Cup final.

Cudmore suffered a series of instances that season culminating in the European final at Twickenham, when he vomited during half-time but was sent back out to play risking a potentially fatal second hit.

Now retired, Cudmore still suffers from the after-effects. He’s seeking compensation, which he says he will donate to charities that promote safer practice, an overhaul of the rugby’s Head Injury Assessment system and a ban on double tackles.

Even in the four years since this instance, rugby has made significant strides, much of it promoted by the “if in doubt, take them out” campaign.

World Rugby say there’s been a reduction in concussions, but from just my own anecdotal evidence reporting rugby matches there seems to be two or more HIAs a game with players removed from action far more readily.

Obviously greater understanding has meant far more reporting and identifying of concussions. But it remains alarming to think that if this represents a reduction, what was the actual extent of it before the penny dropped?

And even today’s stricter assessments don’t take into account a major factor – what if the player isn’t letting on how seriously bad he is feeling?

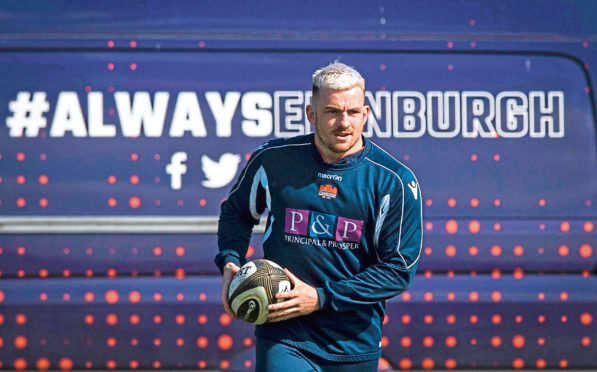

A good example of this dilemma was given by Matt Scott, the Edinburgh and Scotland centre who has returned to action after four months out with concussion.

This was meant to be a big season for Scott. He was returning to Edinburgh from Gloucester intent on getting back in the Scotland team with a view to the Rugby World Cup. Then he took a forearm to the head in a European Cup match against Toulon in October.

He passed his HIA, finished the game and reported for Scotland training for the autumn tests, only to suffer headaches at a simple light weights session.

“It dragged on for months with headaches every day,” he said.

“I thought, ‘Jesus, this is really unusual, I’m taking so long to come back’. But you find that a lot now, guys can’t return to play as quickly as they used to.”

Scott – a law graduate – didn’t feel pressure from inside or outside the game to come back quicker.

“There are guys who wouldn’t care, rugby is their life,” he added. “If it got to the stage where it was a real risk to my health then I would probably stop.

“For someone like Dave (Denton), who is on his third or fourth bad one and has just had a kid, you do start to have those conversations with yourself.”

Matt’s now all-clear – symptom-free – but there are other pressures, he adds.

“You’ve got guys who are perhaps coming to the last of their contracts, they don’t have a club for next year, and they’re thinking, ‘I’ve got a bit of a headache but I’m not going to declare that because I need to play’,” he said.

“Even coming up to World Cup time, if somebody picks up a head knock before they get on the plane to Japan…do you mention it or do you not?”

Scott adds that the SRU medical staff are “really big on you being honest with them” and Edinburgh head coach Richard Cockerill – who must have been asked every week about Scott by myself and media colleagues – “never once asked when I’d be back, just said `come back when you’re ready’”.

Similarly at Glasgow Dave Rennie has been proactive, ending hooker George Turner’s season early and keeping Callum Gibbins out of this week’s crucial game at Leinster.

Even though the club captain was “symptom-free” last Saturday. With this kind of thing, as rugby has belatedly discovered, you can’t be too careful.