The National Trust for Scotland (NTS) has launched one of its more unusual appeals by asking landowners to donate turf to help reconstruct a traditional turf-walled ‘creel’ house in Glencoe.

Creel houses have been completely lost from Scotland’s architectural landscape, but they were a building style that would have dominated in West Highlands rural communities until the 19th Century.

Archaeological excavations in the heart of Glencoe have shown that creel houses were once dotted throughout the glen in small townships and, thanks to the support of hundreds of donors, the Trust plans to recreate one particular building that would have been occupied during the 17th Century and at the time of the infamous Massacre of 1692.

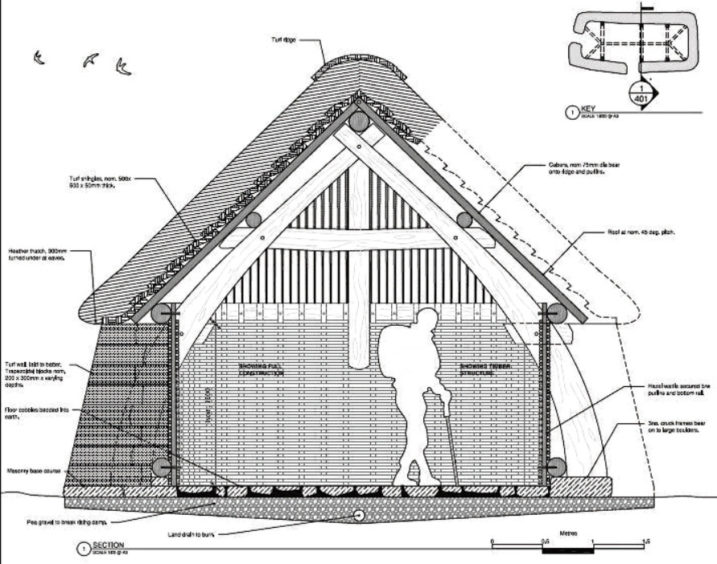

Creel houses combined a sturdy ‘cruck’ frame of timber, with basket-like ‘wattle’ internal walls weaved from freshly cut ‘green’ wood and were lined on the outside with thick, insulating walls built from blocks of turf. The roof would have been lined with thinner turf below thatch, usually made of heather.

Derek Alexander, the National Trust for Scotland’s head of archaeology, explains: “The appeal was based on the results of archaeological investigations in Glencoe at Achtriachtan township.

“This had located the remains of a small settlement that was visible on an 18th Century map and had been mentioned in documents relating to the Massacre in 1692.

“The remains of five houses, four enclosures or kail-yards, and a grain-drying kiln were mapped. The entire floor plan of one house was exposed and recorded by archaeological excavation.

“It was decided that to try and interpret the remains it would be best to attempt to build a replica based on the archaeological evidence but to locate this close to the current visitor centre,” Derek continues.

“Previous work on excavations on numerous house sites at Ben Lawers and the work at Achtriachtan had revealed that houses of this period were often built using a combination of local resources such as stone, turf, timber, heather and withies to make wattle panels.

“A ‘creel house’ is a term that was generally used by visitors to the Highlands from the 17th Century onwards to describe a non-stone built house usually built of wattle panels and turf and sometimes incorporating a timber cruck frame.

“The ‘creel’ element relates to the use of woven wattle panels, like a basket or creel, within the structures which sometimes sat within thick stone and turf walls or form more temporary structures had turves pinned to them, overlapping like shingles.”

The creel house has a fascinating history as Derek reveals: “The historical references to such houses has been discussed by an article by Professor Hugh Cheape which emphasises that very few of these types of structures survived even into the 19th Century as they were largely built of organic components that have rotted away,” he says.

“Some of the references to ‘creel’ type houses are to houses in the central Highlands and in Lochaber. Cameron of Locheil’s House at Achnacarry that was burnt by Government troops after Culloden was a timber structure.”

So who would have lived in creel houses?

“It appears form the historical references to such structures that the same techniques were used to build a wide variety of structures and were not restricted to any social class in particular – some clan chiefs, tacksmen and their tenants may have all occupied similar houses. Perhaps the degree to which each of these were finished off inside may have varied,” Derek says.

Because they were built of organic remains (wood, turf, wicker, thatch and clay), no single example of one of these houses has survived intact so, explains Derek, we only know about them from the limited historical references and from the archaeological record.

“Prior to the archaeological improvements of the second half of the 18th Century onwards it is likely that these types of houses and structures were ubiquitous throughout the Highlands,” he moots.

“They were also built using a range of traditional skills that are no longer in use. An important part of the NTS project is working with skilled traditional crafts people who can both use their skills and pass them on.

“The construction will be a 3D tool for interpreting how people lived in Glencoe over 200-300 years ago.”

The amount of turf required will depend on the how high the turf walls are built.

“Thick, deep-rooted turf is required for the walls which are about 0.8m wide and 1.2-1.4m high. Thinner strips of turf are also required for underlying the heather thatch on the roof,” says Derek.

“In total an area of around 500m2 of turf will be required – so an area 50m long by 10m wide.

Mark Thacker, a craftsperson on the project team who specialises in earth-building, explains: “The task is not quite as simple as heading down to a local garden centre to pick up some turf lawn rolls – it needs to be cut up to 20cm deep and preferably come from an ‘unimproved’ grassland with a stone-free soil.

“By unimproved, I mean a grassland which has ideally not been drained, ploughed, re-sown or artificially fertilised in recent years, as intensive cultivation will tend to weaken the root structure within the turf, which gives it its strength for construction”, he continues.

It is hoped that the turf can be sourced relatively locally, so the team can harvest and transport it to its destination without clocking up too many ‘turf miles’, but they will welcome offers from anywhere in Scotland as part of their search.

While owners of large gardens, pasture fields or moorland edge with moisture-rich peat or clay soils, may be able to donate a patch of turf, the plea is also going out to homebuilders or developers who are planning to clear a plot for construction and will be lifting turf anyway.

The turf needs to be harvested in summer 2021 when the Glencoe creel house building work will be well underway, as it can dry out quickly after being cut.

“As with any replica construction project there is a lot to be learnt through archaeological experiment – the actual process of building,” says Derek.

“This will undoubtedly inform us, through trial and error, and through learning from mistakes just how these houses were built, why they were built, how they were used and what worked well and what didn’t!

“The main challenge is to gather all of the necessary materials for the build. The right sort of turf needs to be located, the right species of timber needs to be located, cut and worked for the main cruck frames and for the wattle panels and the roof support,” he continues.

“Heather thatch needs to be a certain length and needs to be pulled just before it is used. There are therefore lots of logistical issues.

“In the past people would have used a range of local materials that were readily available to them but we now have to consider where we cut timber from, where turf is cut and where stone is collected.

“As many of the Trust’s properties are manged for conservation purposes today we do not want to have a negative impact on these areas.

“As none of the upstanding elements of the house survived in the excavated site, the replica will by necessity have to be part conjecture – part experiment – which will allow a range of different building techniques to be used, interpreted and discussed.”

The creel house will offer a true link to a fascinating past: “The public will enjoy the experience of visiting a full replica house that is based on research from within the glen itself,” says Derek.

“Visitors will step out of the visitor centre into the late 17th Century and be faced with the sights, sounds and smells of previous times.”

If you think you may be able to offer all or part of the turf required, please contact Glencoe National Nature Reserve on 01855 811307 or email glencoe@nts.org.uk

Find out more about the Glencoe Turf House project at nts.org.uk