By Catriona MacKay (international relations student at Dundee University, research interests: Middle East politics), Ian Roache (graduated from Dundee University, Middle East politics expert) and Dr Abdullah Yusuf (politics lecturer, Dundee University).

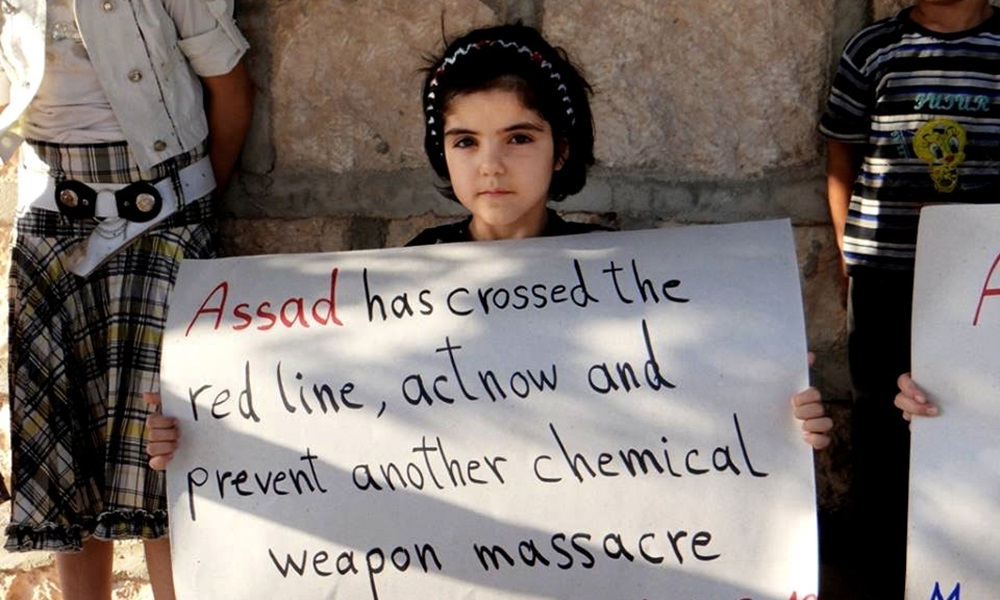

As the world marks the fifth anniversary of the Syrian civil war, what started out as one of many popular uprisings of the Arab Spring has descended into depths of depravity.

The United Nations stopped counting the dead at 250,000 18 months ago.A more recent estimate puts the death toll closer to 470,000 and 1.9 million injured (a combined 11.5% of the total population), along with 45% displaced (both internally and externally), and life expectancy at birth falling from 70.5 years in 2010 to 55.4 in 2015.

The conflict has become dependent on foreign support and material contributions to continue.

Originating from sectarian roots, its duration is being artificially prolonged by the interference of external actors and additionally, has resulted in the extreme fragmentation of opposition forces.

At present there are five main forces opposing the government of Bashar al-Assad (backed by Iran, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Russia): the Free Syrian Army, Islamic Front, Islamic State (or ISIS), Jabhat al-Nusra and armed groups affiliated with the Democratic Union Party of the Kurds (PYD).

Each of which is divided into different groups and fronts, each with the different objectives, and each with different foreign backers (Gulf States, Turkey or Western Governments).

The war in Syria is symptomatic of a wider endemic conflict between Shia Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia, exacerbated by previous interventions by other actors such as the United States and its support for radical groups.

The failure of the Iraqi government to reconcile Shia-Sunni divides within the country, endemic corruption within the Iraqi military, and foreign backing allowed the formation of what would soon become the world’s most brutal terror group – IS.

A 2012 declassified document released in 2015 by the US Department of Defense reveals support for these groups, in their premature form, by the West and its allies in order to destabilise the Assad regime.

It notes proceedings in Syria to be taking a definite sectarian turn thus: “The Salafist, The Muslim Brotherhood, and AQI [Al Qaeda -Iraq] are the major forces driving the insurgency in Syria” and that the “The West, Gulf Countries, and Turkey support the opposition; while Russia, China, and Iran support the regime.”

The document outlines “the possibility of establishing a declared or undeclared Salafist principality in eastern Syria” adding “this is exactly what the supporting powerswant, in order to isolate the regime” despite the threat this would posed to a unified Iraq, predicting the group would use Iraqi territory as a safe haven for its forces. Two years later IS declared its caliphate in eastern Syria and northern Iraq.

The similarity to actual events and those predicted in the document are chilling.

A 2011 report by International Crisis Group (ICG) conceded there was “an Islamist undercurrent to the uprising” however this was not the main factor for peaceful uprisings morphing into all-out war, when compared to decades of socio-economic repression.

By this point however, the brutality of IS was denounced by all, and Frankenstein’s monster was abandoned by its creator. Yet, today, the insurgency is largely dominated by IS, Jahbat al-Nusra, and other al-Qaeda-type groups fanning the flames of a sectarian war and feeding into the larger Shia-Sunni conflict in the region as a whole.

In his 2015 address to the UN General Assembly, Russian president Vladimir Putin criticised US actions in Syria, claiming its “social experiments for export, attempts to push for changes within other countries based on ideological preferences, often led to tragic consequences and to degradation rather than progress. Since the 2003 war in Iraq, the country has been wrought by sectarian violence and this has led to the creation of IS. The repressive authoritarian rule of Assad caused Syrians to revolt, fuelled by the West and its allies supporting Sunni insurgency opposition groups in order to destabilise the regime. War in Syria gave IS the opportunity to spread from northern Iraq into eastern Syria and declare their caliphate.

The US began offensive air-strikes against IS in Iraq and Syria whilst arming supposedly moderate rebel groups on the ground to try to overthrow Assad. Iran, fearful of the prospect of a Sunni government in Shia-friendly Syria, began assisting the Assad regime.

Russia, as a long-standing ally of Syria, deemed all opposition groups, minus the Kurds, to be terrorist in nature and subsequently began air strikes against Western-backed rebels in aid of the Syrian government. Turkey used the opportunity to target the Kurdish Peshmerga to quell separatist notions in its own Kurdish population, with Saudi Arabia-supporting the Sunni opposition groups in order to limit Iran’s influence in the region. The internalisation of the conflict has brought the above powers closer to a direct conflict than ever before with a former advisor to the Saudi royal family cautioning open conflict between Iran and Saudi to be a genuine possibility, and a spokesperson for Putin deeming Russia-Turkey relations to be the “worst in decades.”

The more actors involved, the longer the war lasts as there are fewer acceptable options that would lead to peace. Human Security Report Project found “these wars (internationalized intrastate conflicts) are consistently deadlier than civil wars in which there is no external military intervention” with “the risk of conflict escalationi.e., of higher death tolls ‘increases by 192% if an external state intervenes militarily on the side of the rebels.” From of the turn of the century 90% of all interstate conflict was initiated by a state already embroiled in a civil war, according to the World Bank. Therefore, in the case of Syria there is genuine risk of prolonged unresolved internal conflicts leading to future civil war or even interstate warfare between the main Sunni and Shia powers. Peace, now, is imperative.

The numbers of those dead, injured or displaced by the war in Syria is harrowing, Amnesty International has deemed it to be “The worst humanitarian crisis of our time.” For any peace solution to work for Syria, it must be accepted by all parties involved. In particular, the divide between Shia and Sunni Muslims must be addressed, with Saudi Arabia and Iran acquiescent to any agreement, using their influence to quell and fears in the Syrian Shia/Sunni populations. Fighting can only be stopped, and peace brought to the wider region, when the parties feels there is little to be gained from continuing the conflict and none are threatened by the proposed resolution.

In 2011 former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan as Joint Special Envoy of the United Nations and the League of Arab States presented his six-point proposal as the first of many peace plan for Syria. The Assad government accepted the plan and a subsequent UN observer mission was sanctioned to monitor the implementation of the plan. However, it was then later suspended as the plan failed and the violence intensified. Annan later resigned from his post citing “finger-pointing and name-calling in the Security Council.” This tendency to assign blame and a lack of motivation for cooperation has characterised all attempted peace talks and deals since, resulting in their abject failure.

The involvement of the US and Russia has only served to complicate the war even further, and blocking any possible solution on an international level. Military strategist and historian Edward Luttwak argued other actors should not interfere in the wars of others, and instead it should be allowed to play out as it serves the purpose of bringing peace. By allowing the causes of war to be fought over peace can be reached by either decisive victory or exhaustion leading to a mutually-agreed settlement. Therefore, the Syrian civil war cannot be settled by the US or Russia, instead it must involve regional actors such as Iran and the Gulf States who are party to the wider Shia-Sunni conflict that fuels the Syrian war.

Peace agreements are most likely to be accepted when each side believes the cost of continuing fighting to outweigh potential benefits resulting in a “mutually hurting stalemate.” Recent peace talks in Geneva have resulted in a ‘cessation of hostilities’ with IS, Jabhat al-Nusra “and other terrorist organizations designated by the United Nations Security Council” excluded from the deal. However, with no agreement on which parts of the armed opposition are terrorist, Russia continues to target those deemed as “moderates” and backed by the US and its allies.

Yet, it seems there is no better opportunity for peace than at this current moment. With large swathes of the opposition dominated by al-Qaeda style groups, for the US the removal of Assad could result in political exclusion or a downright massacre for non-Sunni Syrians but, if he wins, the non-fundamentalist Sunni-majority would face renewed oppression and retribution for the sins of their fundamentalist counterparts, along with a strengthened Russia and Iran. Continental Europe, particularly in the south and east, struggles to cope with the influx of refugees, with the European Project being torn apart from within. With the successful recent nuclear deal US-Iran relations have never been better.

As the war drags on and tensions between Moscow and Ankara increase, so too does the possibility of both being dragged into direct confrontation over the Kurds. Russia cannot afford to become further embroiled in the war both in the literal and figurative sense, with its current crisis-stricken economy under sanctions over it activities Ukraine imposed by western powers. The possibility of an open conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia is destabilizing the entire region and with not clear winner insight vis–vis Syria, it appears a “mutually hurting stalemate” has arrived for all parties.

A solution currently being floated by US Secretary of State John Kerry and others is that of federalisation. The Syrian war is rooted in a sectarianism divide of Sunni v Alawite and the rest so any deal must reflect this reality. Federalisation may be the way forward with Syria being split into two sections; one Sunni, and one Shia, Alawite, Christian, Druze etc, reflecting the territory currently held by each group. By providing autonomy for each no group has dominion over the other, thereby reducing the likelihood of future grievances leading to war.

Furthermore, this solution could be favourable to both Iran and Saudi Arabia as neither has ostensibly the upper hand, returning to a balance of power in the region. Equilibrium between these two powers (each tends to promote their version of Islam) would prevent either dominating Syrian internal affairs, thereby protecting the sovereignty of the proposed Syrian federation. For the wider international community, the federalisation of Syria would bring an end not only to long-standing humanitarian suffering but also the biggest threat to international security to date.

Before federalisation can be achieved, however, all violence of Syria’s multi-faceted war must cease and this can only be achieved by agreement of the major powers.

With currently only a fragile “cessation of hostilities” in place each party must commit to a further concrete ceasefire agreement. In the case of the US, all activities – both overt and covert – to overthrow the Assad government should be halted along with all “moderate” insurgency operations. Russia must respect any ceasefire deal and should resist targeting any of the “moderate” opposition, even if they themselves do not believe them to be moderate.

Secondly, it must be recognised that only through the restoration of law and order, and the provision of basic services, can sympathy for groups such as IS be diminished by undermining their support. Consequently, bodies such as the EU should divert funds to restoring Syrian infrastructure, instead of giving large sums to countries such as Turkey to curb migration into Europe. In addition, the UN Security Council should move to authorise a peacekeeping force contributed to by currently uninvolved powers.

Thirdly, regional powers must enter into talks with each other to produce a general consensus of conduct with regards to civil unrest on which to operate in the region to prevent such escalation again. As the economist Jeffrey Sachs noted: “Arabs, Turks and Iranians have all lived with each other for millennia. They, not the outside powers, should lead the way to a stable order in the region.”

If the Syrian civil war can teach us anything it is that intrastate war, stemming from regional ethno-political tensions, can only truly be solved by the relevant powers to the wider conflict, while all other concerned actors should limit their involvement. The war can be seen as the cumulative effect of a societal sectarian divide, aggravated by external pressures resulting in an artificially prolonged conflict with reconciliation becoming increasingly challenging.

If the Syrian civil conflict began, and is continued, via proxy on a sectarian divide it must end reflecting this actuality. Federalisation, therefore, offers the only viable solution. The involvement of external powers has brought these major actors closer to a direct clash than ever before. With the war now entering its sixth year, it is time the international community realised the suffering the Syrian people have endured at their expense. The war must come to an end immediately, once and for all – for everyone’s sake.

Contact the authors:m.a.yusuf@dundee.ac.uk, c.e.mackay@dundee.ac.uk, i.p.roache@dundee.ac.uk