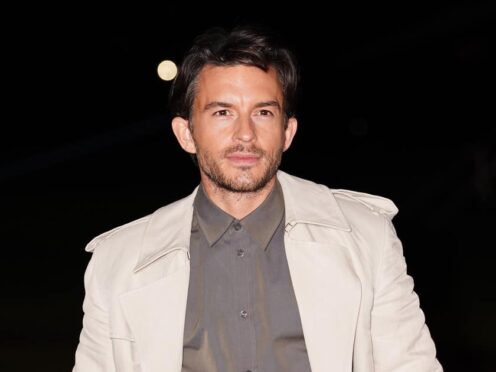

Climber Simon Yates was portrayed as “the man who cut the rope” in the film Touching the Void. Ahead of a stage version at Perth Theatre – and an accompanying talk from Simon – he opens up to Gayle Ritchie…

It is one of the greatest stories of disaster, abandonment and survival in the mountaineering world.

When Touching the Void was released in 2003 it focused on a near-fatal climb that Joe Simpson and Simon Yates made in the Peruvian Andes in 1985.

The two friends, then in their 20s, had set out to be the first to reach the summit of 21,000ft Siula Grande.

They succeeded, but during the treacherous descent Joe broke his leg, leaving Simon to lower him the rest of the way with a rope.

Further disaster struck when Simon – in the dark, with frostbitten fingers and during a blizzard – lowered Joe over a cliff-edge leaving him dangling.

Simon was then faced with a horrific choice – cling on until Joe’s weight pulled him down and they both fell to their deaths, or cut the rope to save himself. He cut the rope.

By some miracle, Joe survived a 50ft fall into a crevasse – unbeknown to Simon who assumed he had been killed – and climbed out and dragged his broken body back to base camp four days later.

In 1988, three years after the harrowing expedition, Joe penned a memoir to document the event. This was subsequently made into the BAFTA award-winning film, Touching the Void.

Its success, however, left Simon feeling rather disgruntled.

In focusing on Joe’s fight for survival, he felt it was economical with his side of the story, that it was skewed, and unfairly condemned him as “the man who cut the rope”.

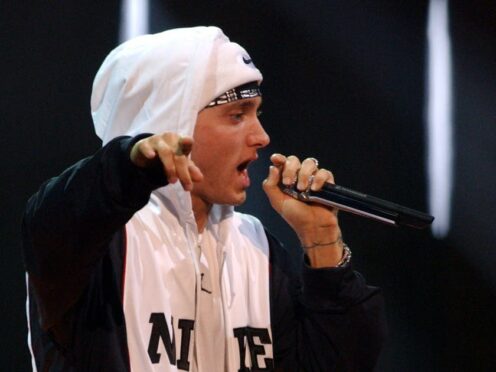

Touching the Void stage adaptation

A recent adaptation of the film for the stage by Scottish playwright David Greig and directed by Tom Morris has prompted Simon to give a series of talks about his mountaineering exploits, and of course, to offer his insight into what happened that fateful day.

He’s presenting it at Perth Theatre on February 28 – this Thursday.

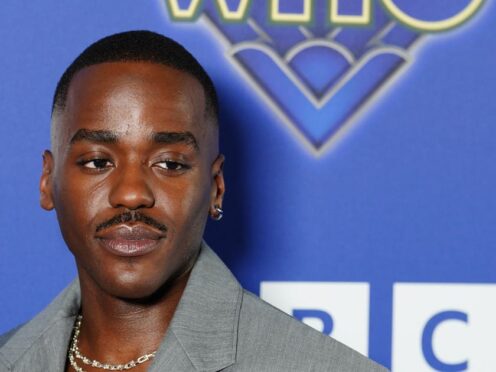

The touring production, also titled Touching the Void, which sees Josh Williams starring as Joe, and Edward Hayter taking on the role of Simon, is at the theatre from March 7 to 10.

Speaking from his home in Cumbria, Simon tells me that while he finds the stage version “a little abstract”, he enjoyed it.

“It’s open to more interpretation (than the film) from the audience,” he reflects.

“It’s more about why people climb mountains and I found that interesting.

“The actual story of what happened can be a bit morbid unless you put humour into it, and they’ve done that with the stage version, which is good.”

Touching the Void

No conversation with Simon, 55, would be complete without asking about the movie.

Given he feels it was selectively edited and portrayed him in a negative light, I’m almost reluctant to mention it. But, of course, I have to.

I raise the fact that, just before the credits, a message rolls onto the screen stating that Simon faced “strong criticism” from the climbing community.

This is something he absolutely refutes. “That’s rubbish,” he scowls. “Nobody had any issues with what I’d done in the climbing community at all; they understood. Why then should I have issues? Most people were very supportive and sympathetic.”

Many people have waxed lyrical about the morality of Simon’s decision to cut the rope, but he argues there was no time to reflect on morals.

“I was looking for a solution to the predicament I was in,” he says.

“I took a long time to come up with a solution and by then, my own position was desperate.

“Normally we would be anchored to the mountains. We put tools into rocks or ice to secure ourselves.

“But in this case I was the anchor and I was going to be pulled off. Over time, I got colder as I sat on a snow cliff.

“The snow was collapsing and sooner or later I was going to be pulled off the mountain to my death.

“I got a knife out of my rucksack, which was difficult because I was losing feeling in my hands, and cut the rope. It wasn’t a great decision; it was a pragmatic act made in the moment.

“I didn’t have the luxury of moralising – you don’t when you’re making potentially life or death decisions – so I don’t see it as an ethical dilemma.”

When Joe made it back alive, Simon was surprised, overjoyed and emotional.

Did he – or does he – feel any guilt over what happened? “It wasn’t necessary to feel guilt over what I’d done,” he says.

“It was distressing to see Joe in such a bad way and the priority was getting him to hospital.”

Simon and Joe, who first met in 1984 in Chamonix at a campsite full of British climbers, don’t keep in touch these days although Simon insists it’s not because there’s any ill-feeling between them.

“We lead totally different lives,” he reasons. “We’re very different people from different backgrounds.”

Indeed, Joe has always defended Simon and acknowledged he “put his life on the line” for him, once stating in an interview: “The paradox is that, by cutting the rope, he put me in a position where I could save myself.”

The ordeal might have tainted the concept of climbing mountains for many people. But not Simon, who has made it the focus of his life for almost four decades, travelling to some of the world’s most isolated destinations to seek out summits.

However, becoming a father (he has a 12-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter) had a major impact on Simon’s risk-taking sensibilities: “It meant my sense of responsibility changed – the children are there in your mind when you’re up mountains.”

While the kids have yet to find their feet in the mountains – “I’m not pushing them to be climbers” – they are massive outdoors fans and love family holidays with Simon and their mum, Jane, in the Scottish Highlands and Islands.

Simon, who says Eigg is among his favourite places in the world, has done lots of climbing in the Cairngorms and Mamore mountains.

He loves Ben Nevis “because it offers fantastic winter climbing and dozens of routes up.”

Simon is keen to tackle a group of mountains in South Georgia but the logistics of getting there are somewhat tricky: “You need a yacht and you have to sail from the Falkland Islands! And there’s no organised rescue to help you.”

His advice to anyone keen to get into mountaineering is to start with rock climbing.

“That’s the entry point for most people. Go to your local climbing wall, get some instruction and then get outside.

“I rock climbed across the UK and did a lot of winter climbing in Scotland, North Wales, the Lake District and the Alps. It’s all about gaining experience. Then you can tackle bigger and more remote mountains.”

Simon, who leads mountaineering expeditions across the globe, will give deeper insights into his experiences at his lecture.

He describes this as a “smattering of chat about my climbing life from beginning to recently,” adding: “I’ve had a huge variety of experiences in amazing places. There’ll be a fair bit of dry humour. There’s not a Q&A – those tend to fall flat – but people can talk to me and ask me questions personally.”

The illustrated lecture features spectacular images and film of the most remote and rarely explored mountain ranges from the Arctic to the Antarctic and Alaska to Central Asia.

“Hopefully it will inspire people to get out there and enjoy the mountains,” adds Simon.

Information

Simon’s talk, My Mountain Life, is at Perth Theatre on February 28 at 7.30pm. The stage adaptation of Touching the Void is at Perth Theatre from March 7 to 10. It also shows tonight at Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre. Other dates include: Hong Kong Arts Festival, February 21 to March 2; Eden Court Theatre, Inverness, March 14 to 16, and Bristol Old Vic, March 19 to 23. Simon’s talk also runs at Mull Theatre on March 9, Corran Halls in Oban on March 11, The Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh on April 1 and Eigg Community Hall on April 3.

For tickets for both Simon’s talk and Touching the Void, see www.horsecross.co.uk