The foundation stone for what was to become Dundee Royal Infirmary was laid in 1794.

The idea for Dundee’s first infirmary began with a surgeon and a minister.

Robert Stewart and the Reverend Dr Small.

They began to collect money in 1782 and by 1798 the first infirmary was opened.

The two-ward and two-storey white-washed building on the north side of King Street had accommodation for 20 patients with a building cost of £1,400.

Patients paid 3s 6d a week for their board.

Fever cases were free.

The first patient was William Dove of Monikie who was sent home after two weeks “with proper medicines.”

Patients were encouraged “not to presume to play at cards or dice, not to smoke tobacco in the wards” and “not to throw any dirt over the windows”.

In those days alcohol was prescribed for medicinal purposes and the unhappy task to sample the malt liquors then consumed in quantities fell to the DRI’s first nurse.

Mistress Farquharson was paid six shillings a week for her trouble.

In 1819 a charter was granted and the hospital was able to call itself Dundee Royal Infirmary and Asylum.

Later, as Dundee expanded, the asylum moved out to Liff, ultimately becoming Royal Dundee Liff Hospital.

The infirmary then became Dundee Royal Infirmary.

Two wings were added between 1825 and 1827 which doubled capacity, but this was only a short-term solution as Dundee’s population continued to explode.

In 1826 there were 577 in-patients and 1,166 out-patients.

The DRI was quickly running out of space.

For instance, provision had to be made in 1847-48 for the reception of 3,000 patients suffering from typhus and other epidemic fevers beside the ordinary medical cases.

At this time, patients came from towns and parishes across Angus, Fife and Perthshire.

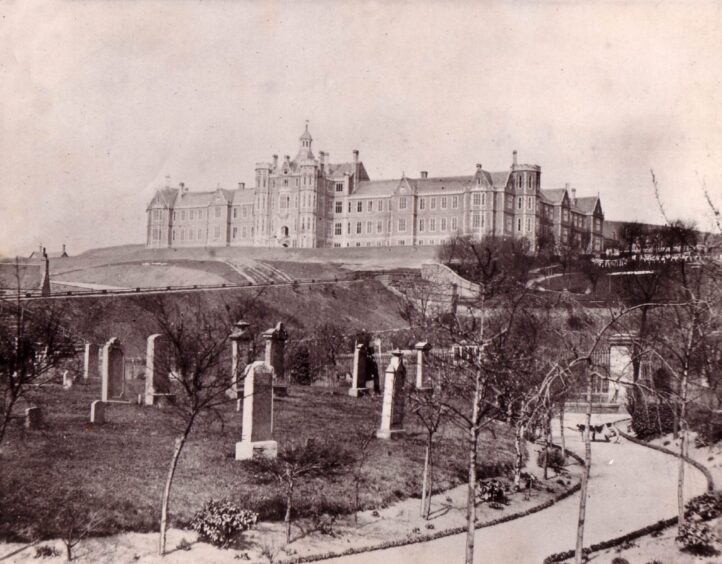

New hospital taking shape in 1852

Dundee’s population alone rose from 30,000 in 1821 to 80,000 in 1851 and it was clear that the medical needs of a fast-growing region couldn’t be served by the tiny hospital.

Towards the mid-1800s, construction of a new Royal Infirmary was recommended on a site near Dudhope Castle.

Work began in 1852.

It opened on February 7 1855 with accommodation for 300 patients.

Over the next century and a half the new site would greatly expand.

A children’s ward was added in 1883.

Sir James Caird provided new buildings for maternity services and cancer patients.

As DRI grew, it became the central hospital for the whole region and gained a reputation for its high standard of medical care and treatment.

Its presence also allowed the development of a medical school in Dundee in the 1890s.

In 1889 King’s Cross Hospital was opened to treat infectious diseases following earlier temporary ventures, and thereby reduced some of the pressure on DRI.

In the earlier years of the century the casualty department at DRI saw mill workers who had limbs trapped in machinery and other industrial accidents.

There used to be more serious falls when people worked at heights without safety gear.

During the First World War, the DRI provided accommodation for a large number of wounded soldiers before the military hospital wing closed in 1919.

By 1926 there were 8,093 in-patients and 15,379 out-patients.

In 1929 they were joined by the former infirmary at the East Poorhouse which had been operated by Dundee Council as Maryfield Hospital since 1929.

A maternity section was opened at DRI in 1930.

A new pathology department opened in July 1935.

In 1948, the infirmary governors handed over the title deeds of the infirmary to the Department of Health, marking the launch of the new National Health Service.

However, it was again clear that Dundee’s population was getting too big for its hospital facilities and plans were drawn up to build a new hospital at Ninewells.

This endeavour took some time to realise, but the result was one of the most modern teaching hospitals in the world which officially opened in October 1974.

At this point Maryfield closed.

The writing was on the wall for Dundee Royal Infirmary

In the 1970s, an average of 50,000 people a year passed through A&E at DRI.

Over the years further departments were added, including the diagnostic radiological department, the neurosurgical unit, a £1 million body scanner unit and urology clinic.

In November 1991 a leading staff member focused public attention on DRI’s apparent shortcomings before a Dundee Discovery Lecture given by an American trauma expert.

Professor David Rowley said Dundee’s trauma service would not even qualify as second rate and public confidence in accident and emergency was misplaced.

“The public perception is that if you are injured and you get to hospital, you’re okay.

“In fact, if you go to a certain hospital on a certain day, it’s lethal – we all know that.”

DRI lacked an intensive care unit.

Anyone in urgent need of an ICU had to be whisked by ambulance to Ninewells.

Other DRI consultants were also known to believe that the elderly hospital was no longer functioning properly and services should be moved as a matter of urgency.

Confidence was dented.

Overnight, the momentum to relocate DRI’s A&E services accelerated.

A month later health service managers announced that poly-trauma (multiple injury) victims in Tayside would bypass DRI and be admitted to Ninewells.

All other A&E cases would continue to be handled at DRI.

For now.

In 1995 it was announced DRI would close with all its services transferred to a new, upgraded site at Ninewells, with the £28m project to be completed by 1998.

Dundee communists organised a protest at DRI where they dressed as skeletons and injured patients to highlight “excessive waiting lists and inadequate healthcare”.

A coffin with “NHS RIP” inscribed on it “represented the far from adequate health service which is now being stripped to the bone”.

End of an era in Dundee

Dundee’s much loved but out-dated hospital on the hill closed in November 1998.

The last department to leave the listed building, which was sold to a Jordanian-based businessman, was accident and emergency.

The Courier said: “The new department will handle 60,000 patients a year.

“Every week staff see accident victims with very serious injuries, a large number from car crashes on the fast trunk roads throughout Tayside.

“People with life-threatening injuries, be they from road accidents, stab wounds or industrial accidents, should now have a better chance of survival with the new department right next door to the intensive care and coronary care units.

“In the past such patients have been taken to the infirmary to be stabilised and given emergency treatment but had to endure a hazardous trip by ambulance across town, often in the early hours, if they required intensive care back-up.

“While the infirmary has always seen a lot of blood and guts, accident and emergency has emerged as a specialism over recent years as more and more can be done to help.”

The new A&E department was a modern facility in the newly built extension to the south of the Ninewells site treating “everything from stubbed toes to cardiac arrest”.

DRI was cordoned off to make way for the bulldozers.

The original building survived and became part of the Regents Gardens development.

Generations of local people turned to the DRI in their hour of need.

Some even grew to love the lingering antiseptic aroma in its ancient corridors.

On a wall at DRI in the 1970s there was placed the text of its guiding ethos.

Care will be offered as it is needed regardless of their presenting illness, age, gender, religion, national or ethnic group or their sexual orientation.

This is the tradition that was nurtured and served Tayside and north Fife so well.

Conversation