It’s a dark Saturday evening in the mid-1980s. I’m at the window waiting for my Papa to come back from the football.

After the Pink Panther and before Doctor Who, the familiar hum of the results man’s received BBC pronunciation chirps away in the background.

Then we hear it.

Brechin City one, Forfar Athletic nil.

From the depths of the house, somebody somewhere will then respond: “Aye, Granda Strachan would be pleased with that.”

It’s him I’ll be thinking of this Remembrance Sunday.

Although he died when my dad was a child, my Angus-born great grandfather was forever a part of our lives.

We’re one of those families who immortalise our ancestors to the point I now tell stories of people that even my parents didn’t meet.

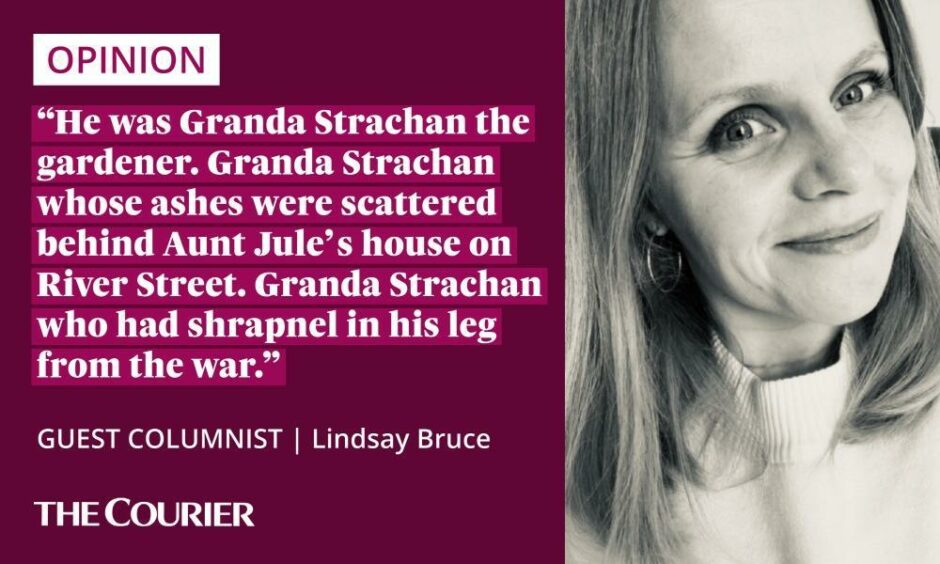

He was Granda Strachan the gardener.

Granda Strachan whose ashes were scattered behind aunt Jule’s house on River Street.

Granda Strachan who had shrapnel in his leg from the war.

But until recently I didn’t know the origin stories.

Four sons all sent to serve

Abe, as my great gran Ruth called him, was one of four brothers for James and Elizabeth whose address, according to my Find My Past search, was on a street called Kinnaird in Brechin.

With their sisters, the family occupied two rooms.

Some of the older children had already moved out by the 1911 census but when the First World War broke out all four sons served.

It was never spoken of in great detail but Albert, John, David – and we believe, James – returned changed. If at all.

Jonny came home missing limbs. “Blown off” was all we were ever told.

Another brother lost his life and never returned.

Another was gassed and although he made it back to Scottish shores he died 18 months later.

Granda survived, but not unscathed

My ubiquitous Granda wore a calliper for the rest of his life.

I grew up hearing stories of him crawling through trenches for miles after being shot.

The photos depict a warm man who loved his grandchildren. But the reality was a changed man who suffered so much loss and pain I can’t help but think about how it altered our collective DNA.

Imagine leaving with your brothers and coming home maimed but alive, when your siblings haven’t been so “lucky”.

I can’t. But I know my lineage and the futures of my own children were changed because of it.

I know we need the armed forces, but when my son talked about joining I did not react well.

And I’d go so far as to say that all of our lives have been altered by the struggle and the trauma of our elders.

I wear my poppies on Remembrance Sunday and I feel their pain

A few years ago I was in Westminster for work and found myself unable to move as I came past a field of remembrance.

“The significance of the poppy is as relevant today as it ever was, while our Armed Forces continue to be engaged in operations overseas and often in the most demanding of circumstances.”

The Prince and The Duchess have launched @PoppyLegion’s Centenary Poppy Appeal. pic.twitter.com/ul8lx3t8OO

— The Prince of Wales and The Duchess of Cornwall (@ClarenceHouse) October 28, 2021

Every poppy in the vast blanket represented a fallen soldier.

I felt real grief. There was a sense of pain in those poppies.

I struggled for a while even to wear those red pins for fear it somehow glorified war.

Now I try to wear two for Remembrance Sunday: a red one to pay homage to the fallen, and a white one representing a hope for a future without bloodshed.

Granda Strachan’s future wasn’t without bloodshed though.

Another generation, another war

He would eventually move to Lanarkshire and had two girls and two boys.

There was Margaret, my gran; aunt Bet, uncle Fergus and uncle Jimmy.

Jimmy, the likeness of his dad, and as legend would have it, the source of my blonde hair, was close to my gran.

So I’m told anyway.

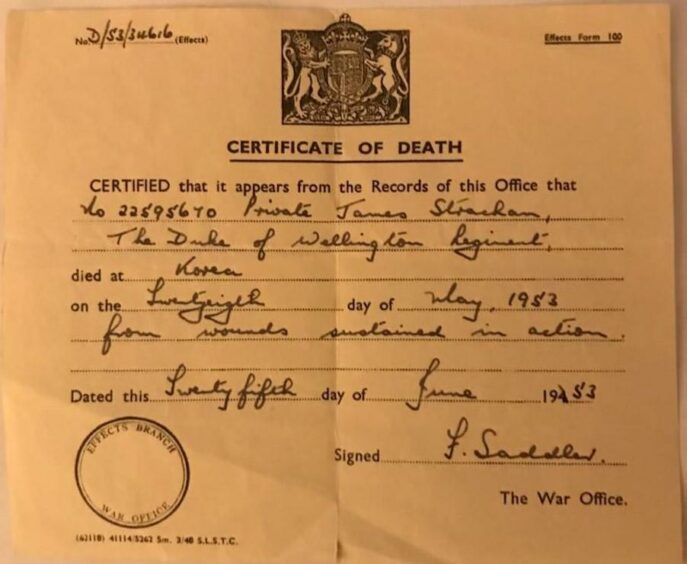

Because he too was gone before ever I lived. This time in Korea.

On May 27 1953 the apprentice bricklayer, who had been called up for national service, was wounded.

On May 28 1953 he died.

At 17 he won the world drumming championship with his pipe band.

By 22 his short life had been snuffed out.

It would be years before his name was added to a war memorial but that didn’t stop my gran mourning him every day afterwards.

She waited 40 years to put flowers on a grave

‘Our Jimmy’ was always part of our lives. Ironic, in that he never actually was.

She told me time and again about receiving the telegram.

I can’t even bear to think about my wee gran being that heartbroken.

Her mum, Ruth, died with only a photo of Jimmy’s grave.

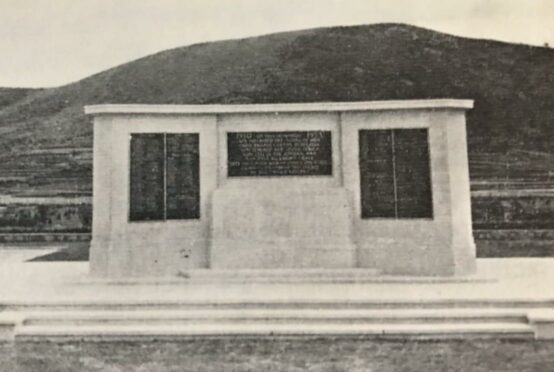

And I was 20 before a Korean War Memorial was erected in the Bathgate hills.

I’ll never forget the tsuanami of fresh grief when, for the first time in her life, my gran was able to lay flowers in remembrance of her baby brother 40 years after his death.

Forty years.

My chest tightens just writing that.

Their blood still runs through me this Remembrance Sunday

Last year I did one of those DNA tests.

I was vaguely hoping for something surprising but it turns out I’m fact as vanilla as it comes; the most exotic line was from Ulster.

One of the strongest threads of my DNA came from the north-east of Scotland though, just as I knew it would.

Brechin, River Street, Kinnaird and the Strachan line are part of who I am.

I’m me because of them. Their blood runs through me.

And we are all of us “us” because of the sacrifices our elders made. The peace they fought and died for, but also what they became because of war.

Forgetting all of that might make things easier this Remembrance Sunday but it’s a privilege I never want to have.

- Lindsay is on Twitter @llbruce